- Why Securonix?

- Products

-

- Overview

- Securonix Cloud Advantage

-

- Solutions

-

- Monitoring the Cloud

- Cloud Security Monitoring

- Gain visibility to detect and respond to cloud threats.

- Amazon Web Services

- Achieve faster response to threats across AWS.

- Google Cloud Platform

- Improve detection and response across GCP.

- Microsoft Azure

- Expand security monitoring across Azure services.

- Microsoft 365

- Benefit from detection and response on Office 365.

-

- Featured Use Case

- Insider Threat

- Monitor and mitigate malicious and negligent users.

- EMR Monitoring

- Increase patient data privacy and prevent data snooping.

- MITRE ATT&CK

- Align alerts and analytics to the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

- MSSPs

- Scale multi-tenant security with predictable economics.

-

- Resources

- Partners

- Company

- Blog

Threat Intelligence, Threat Research, Threat Security

Analyzing Dead#Vax: Analyzing Multi-Stage VHD Delivery and Self-Parsing Batch Scripts to Deploy In-Memory Shellcode

By Securonix Threat Research: Akshay Gaikwad, Shikha Sangwan, Aaron Beardslee

January 14, 2026

tldr:

Securonix Threat Research has been tracking a stealthy malware campaign that uses an uncommon chain of VHD abuse, script-based execution, self-parsing batch logic, fileless PowerShell injections and ultimately dropping RAT. The attack leverages IPFS-hosted VHD files, extreme script obfuscation, runtime decryption, and in-memory shellcode injection into trusted Windows processes, never dropping a decrypted binary to disk. This research breaks down each stage at code level, highlighting modern attacker tradecraft that bypasses traditional detection mechanisms.

Modern malware campaigns increasingly rely on trusted file formats, script abuse, and memory-resident execution to bypass traditional security controls. Rather than delivering a single malicious binary, attackers now construct multi-stage execution pipelines in which each individual component appears benign when analyzed in isolation. This shift has made detection, analysis, and incident response significantly more challenging for defenders.

This research documents a real-world, multi-stage DeadVax campaign that exemplifies this evolution in attacker tradecraft. The infection chain begins with a phishing email delivering a Virtual Hard Disk (VHD) hosted on IPFS infrastructure and progresses through a sequence of Windows Script Files (WSF), heavily obfuscated batch scripts, and self-parsing PowerShell loaders. The final payload is delivered as encrypted x64 shellcode which comes out to be AsyncRAT, injected directly into trusted Windows processes and executed entirely in memory—without ever dropping a decrypted executable to disk.

Unlike many reports that focus solely on the final malware family, this analysis provides a code-level breakdown of the entire delivery framework, from initial access to in-memory execution. Each stage is reversed and explained in detail, exposing how attackers abuse legitimate Windows functionality to achieve stealth, persistence, and long-term control while evading both static and behavioral detection mechanisms.

Key Findings:

- Abuse of VHD files for initial access:

The campaign uses IPFS-hosted VHD files disguised as business documents (DOCX/PDF) to bypass email gateway controls and reduce user suspicion. - Script-centric delivery chain:

Execution flows through WSF, batch, and PowerShell scripts, avoiding traditional malware binaries during early stages and complicating static detection. - Extreme batch obfuscation and self-parsing logic:

The batch stage employs environment variable explosion and reads its own contents to extract an encrypted payload, effectively turning the script into a payload container. - Multi-layer runtime string deobfuscation:

PowerShell strings are protected using a combination of Unicode junk insertion, Base64 encoding, rolling XOR decryption, and ROT-style character shifting, ensuring no meaningful indicators exist in cleartext. - Fileless payload staging:

The final malware stage is stored as noise-polluted Base64 data, decoded into raw shellcode and never written to disk in decrypted form. - In-memory process injection:

The loader injects shellcode into trusted, Microsoft-signed processes using native Win32 APIs (OpenProcess, VirtualAllocEx, WriteProcessMemory, CreateRemoteThread). - Reinfection prevention and execution stability:

A marker-based memory scan prevents multiple injections into the same process, demonstrating mature operational tradecraft. - AsyncRAT delivered as encrypted shellcode:

Dynamic analysis confirmed that the shellcode deploys a fully functional AsyncRAT implant capable of long-term surveillance, data exfiltration, and follow-on attacks. - Defense evasion by design:

Anti-sandbox checks, persistence rotation, execution throttling, and memory-only payloads collectively reduce detection and forensic visibility.

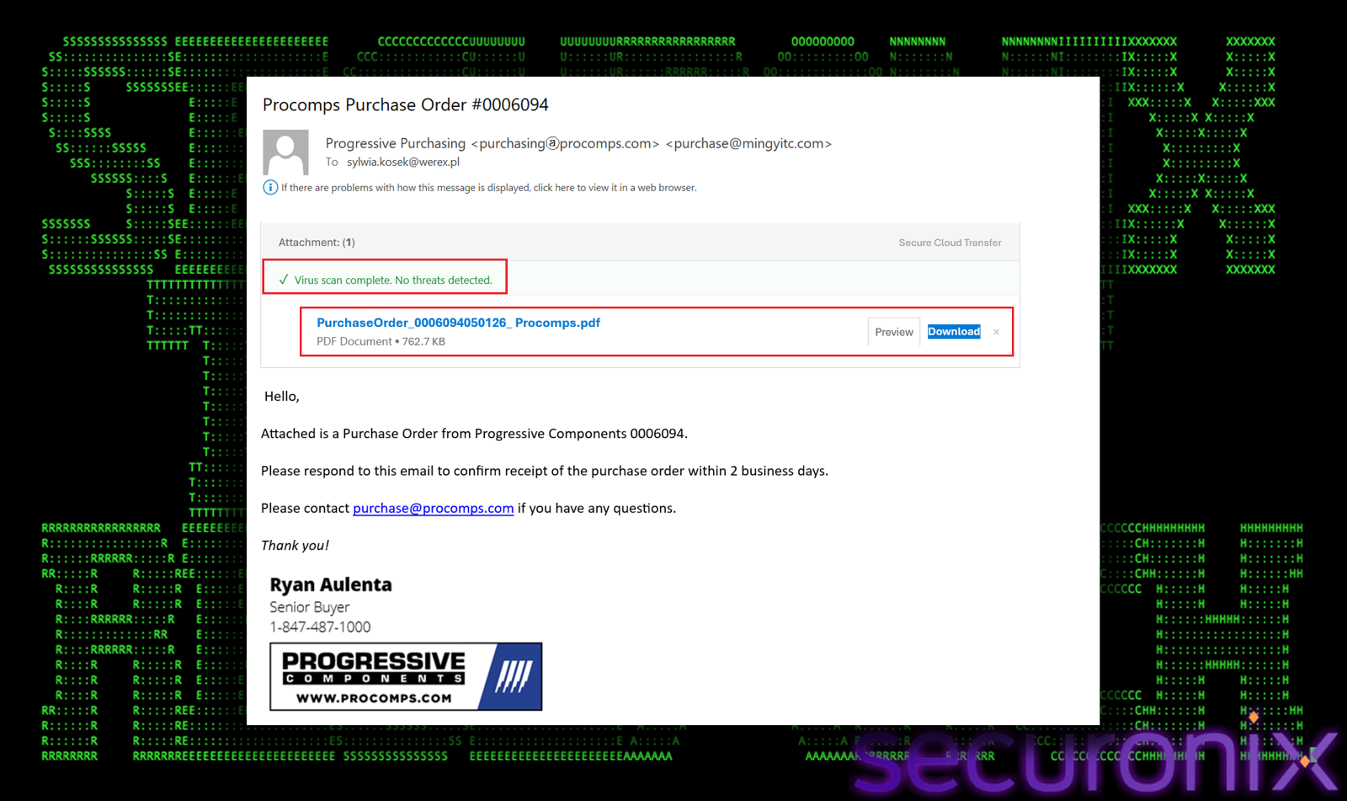

Initial infection: Phishing Scam

The attack begins with a phishing email impersonating Progressive Components (procoms.com), a legitimate global supplier of tooling components. The from name in the email is displayed as “Progressive Purchasing” and the email header shows a double address format: “[email protected]”, “[email protected]”. The attacker spoofs procoms.com via display name, but the actual sending domain is likely the compromised or malicious mingyitc.com. It visually tricks the user into thinking it’s from Progressive.

Figure 1 Scam Email

The subject line implies a formal business transaction, the body demands a response within two days, creating artificial urgency. It targets employees, suggesting a targeted spear-phishing campaign rather than generic mass spam. The email also includes a fake “Virus scan completed. No threats detected” banner green lighting the attachment. This is a psychological trick to disarm the user’s questions. The email says the attachment is a PDF, however the downloaded file actually comes out to be a virtual hard disk .vhd container.

The download button links to a URL hosting the VHD file. The attacker abuses IPFS via a w3s.link gateway to host the malware with this link at https[://bafybeiaj6jw2xhbppgji757tn3hg5uu6splaa5gyydkwnzwprzakcp44ve.ipfs.w3s.link/PurchaseOrder_0006094050126_%20Procomps_Docx.vhd

The long string of random characters in the link is a content identifier. In IPFS, files are addressed by the hash (content), not their location. In short, the email does not contain the malware; it contains a standard HTML link. Traditional email gateways scan attachments well, but scanning every link is harder. When the gateway scans this link it sees a valid SSL certificate from a reputable web3 provider and it often lets the email through to the user’s inbox.

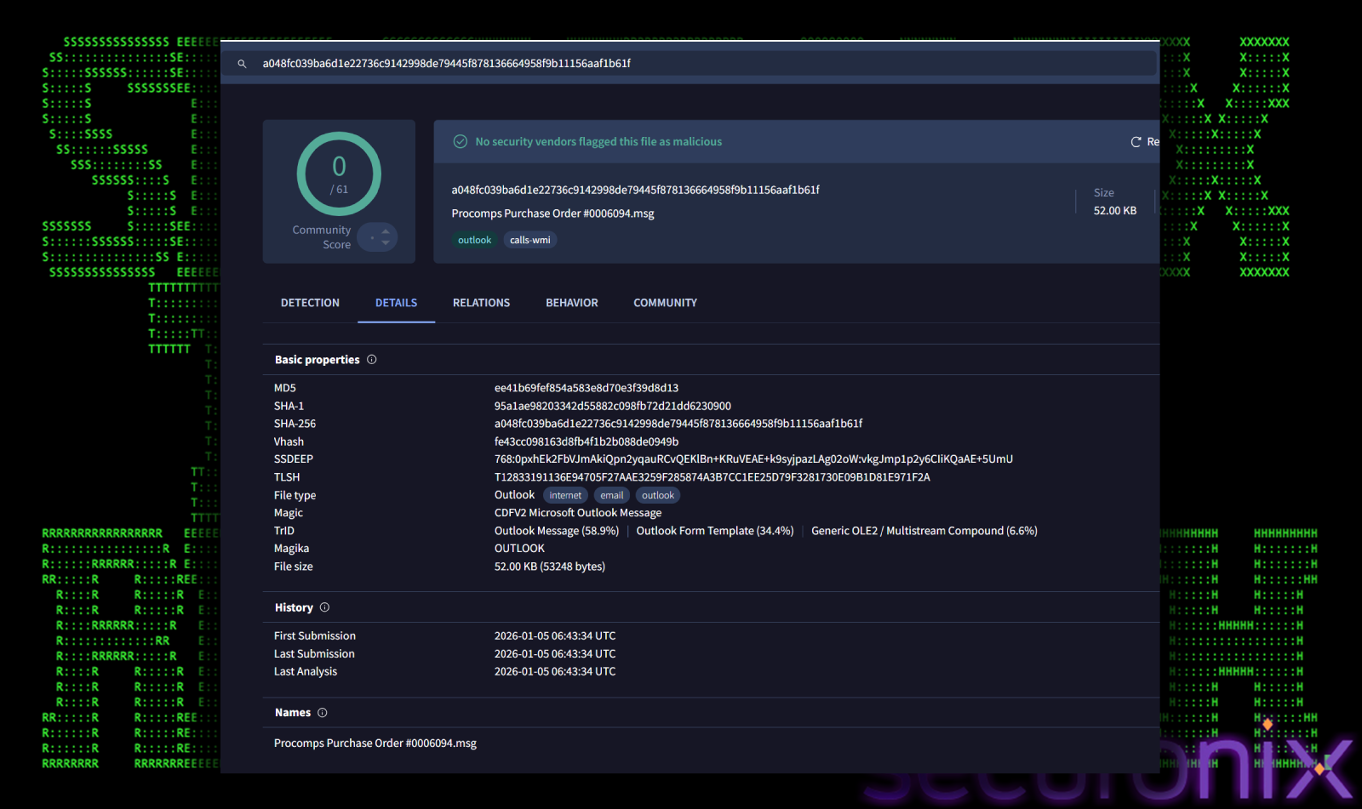

At the time of writing, we analyzed two of such emails, part of this campaign, and they all scored zero on Virus Total.

Figure 2 VT Detections

Stage 1: VHD

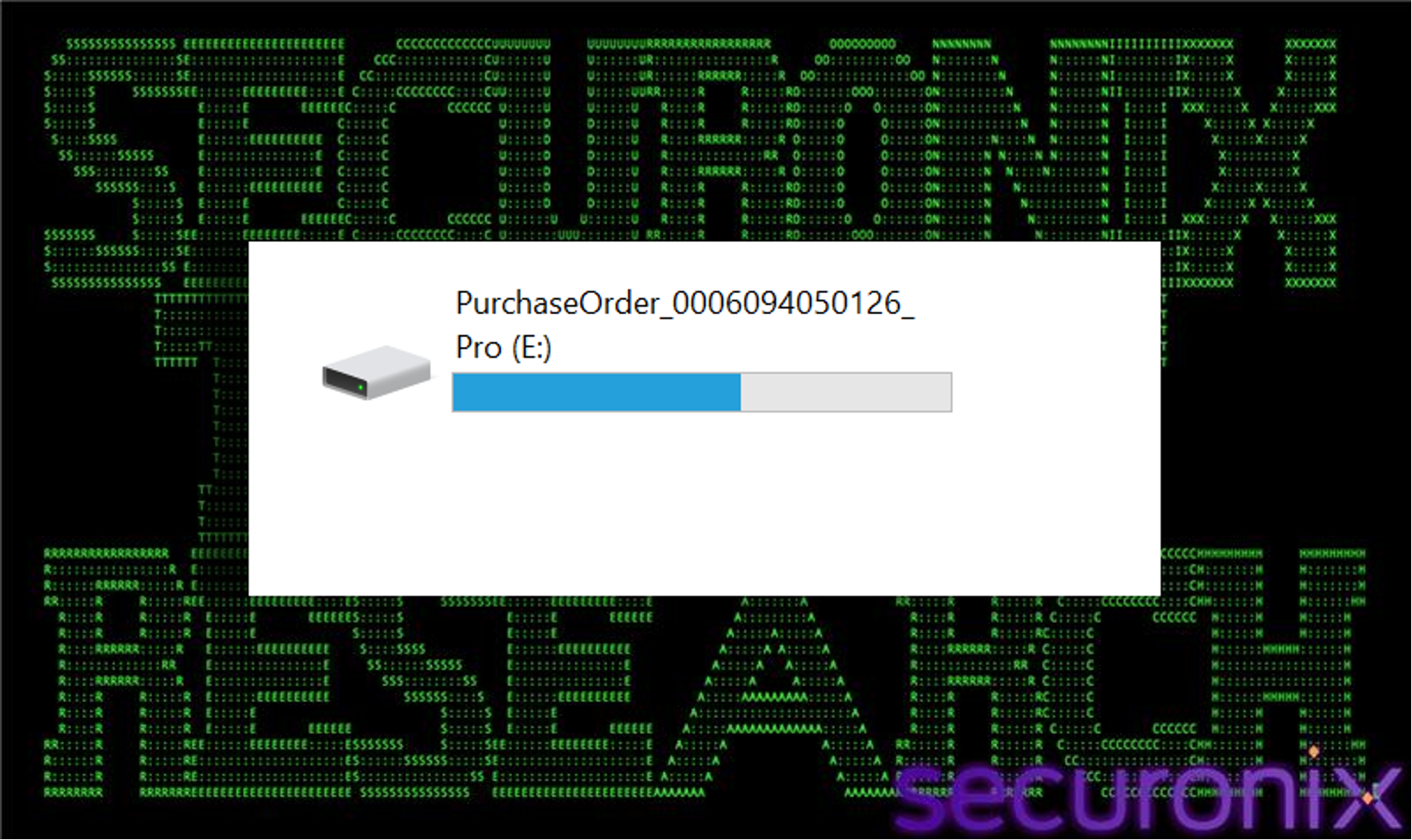

After downloading, when a user simply tries to open this PDF-looking file and double-clicks it; it mounts as a virtual hard drive. Using a VHD file is a highly specific and effective evasion technique used in modern malware campaigns. This behavior shows how VHD files bypass certain security controls. The primary reason malware authors package payloads inside container formats like VHDIS or image files is to bypass the mark-of-the-web (MotW). When you download a stand-alone Exe file from the internet, (via the browser) tags it with a special NTFS alternate data stream called Zone.Identifier. This “Mark of the Web” tells the OS the file came from an untrusted source.

Figure 3 VHD mounted

On the side when you download a VHD file, the VHD file itself gets the mark of the web. However, when the user double clicks the VHD file to mount it (which Windows 10 or 11 does natively), Windows mounts it as a new logical drive. The file system inside the VHD is treated as a separate volume and the files inside the VHD file do not inherit the mark of the web from the container. To the operating system, they appear as local files residing on a local disk.

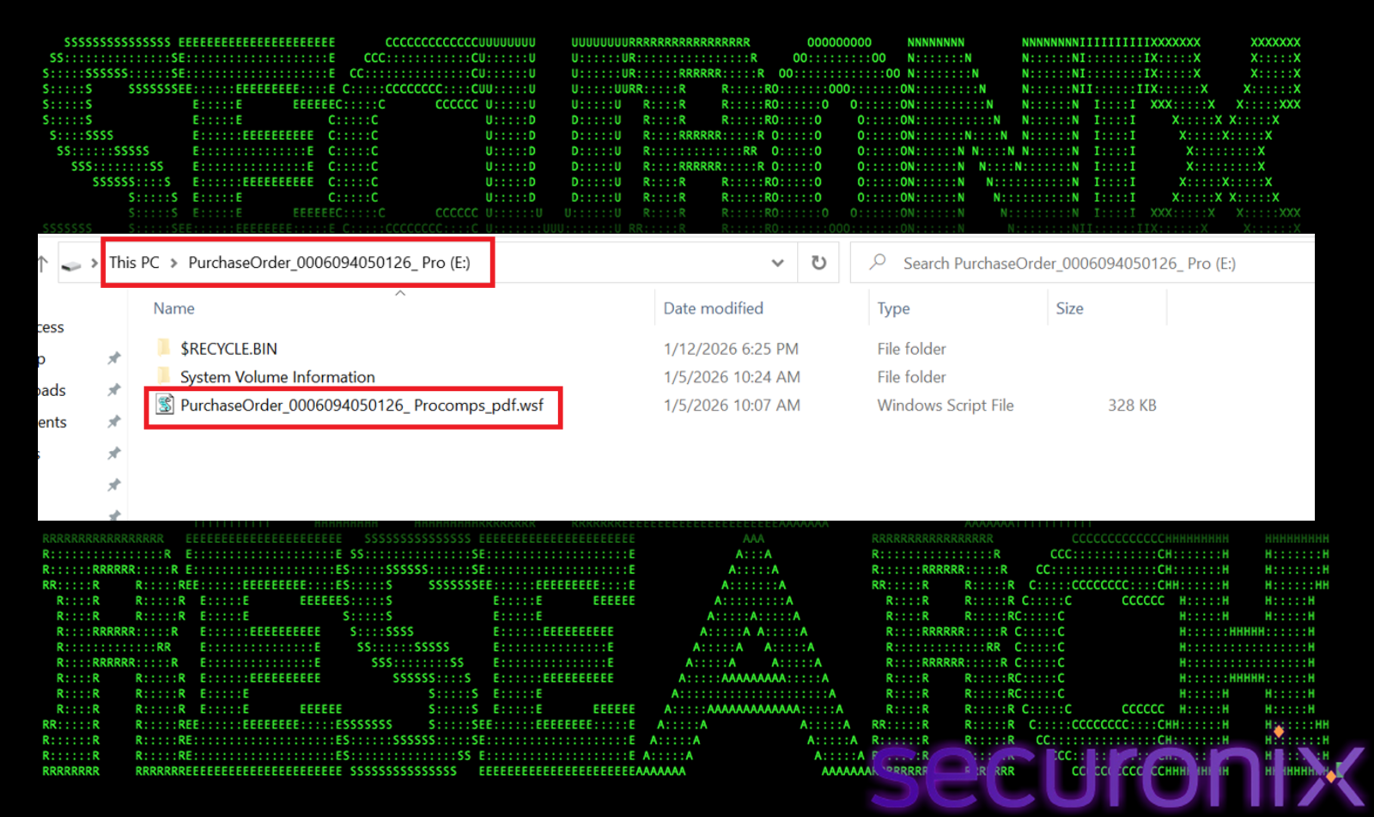

As shown in the image below, the mounted drive E: contains a WSF script. Windows SmartScreen may not scan it as aggressively and it will execute without the standard “untrusted file” warning prompts. Once mounted the user sees a folder view that looks indistinguishable from a USB drive or local folder. The file name purchaseorder…pdf.wsf is designed to trick the user into thinking it’s a PDF document, relying on the user hiding file extensions or ignoring the .wsf suffix.

Figure 4 wsf file with double extension

Double-clicking the WSF file executes the VBScript engine, which then drops and runs a .bat file, which will be used to effectively load the final payload.

Stage 2: Code execution through WSF

The WSF file masquerades as a purchase order so it has a double extension. It looks like a PDF file but it is a WSF file. Unlike simple VBA macros WSF files are XML-based containers that can execute various scripting languages. This script is heavily obfuscated and contains numerous variables with random names and short string fragments. The script first concatenates these variables in a specific order to form the complete encrypted data string. Below is the line which performs the final concatenation:

Ile81Qhu4X6jg

Similarly, the encryption key is also stored as variables later in the script. The variable Cpnef4BbiQn48THoQJ5 is the result of this concatenation. Once Ile81Qhu4X6jg (Data) and Cpnef4BbiQn48THoQJ5 (Key) are fully assembled, they are decrypted.

It actually has a three-step routine to decrypt the payload:

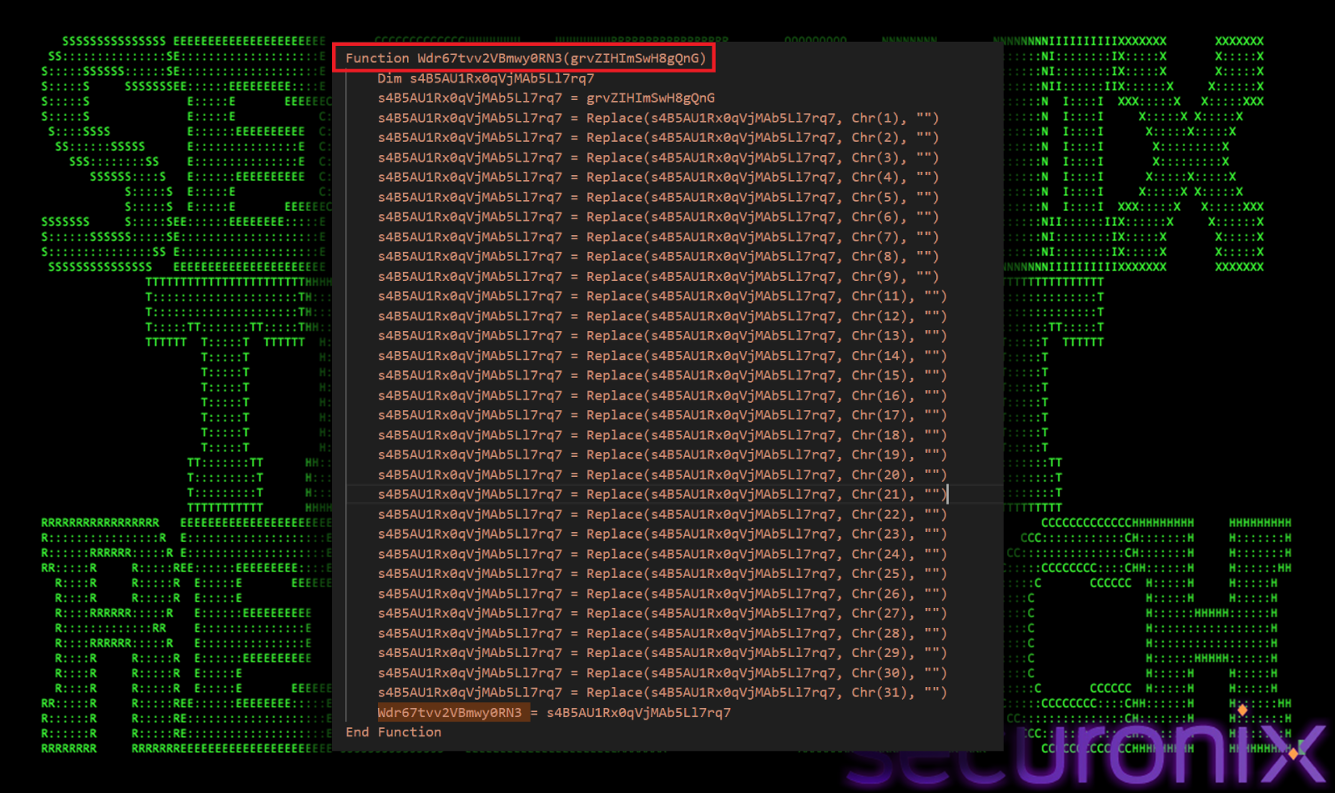

First it cleans. There is a function (Wdr67tvv2VBmwy0RN3), which removes widely used controlled characters (ASCII values 1 to 31) from both data and key strings. (shown in image below)

Figure 5 Clean up function

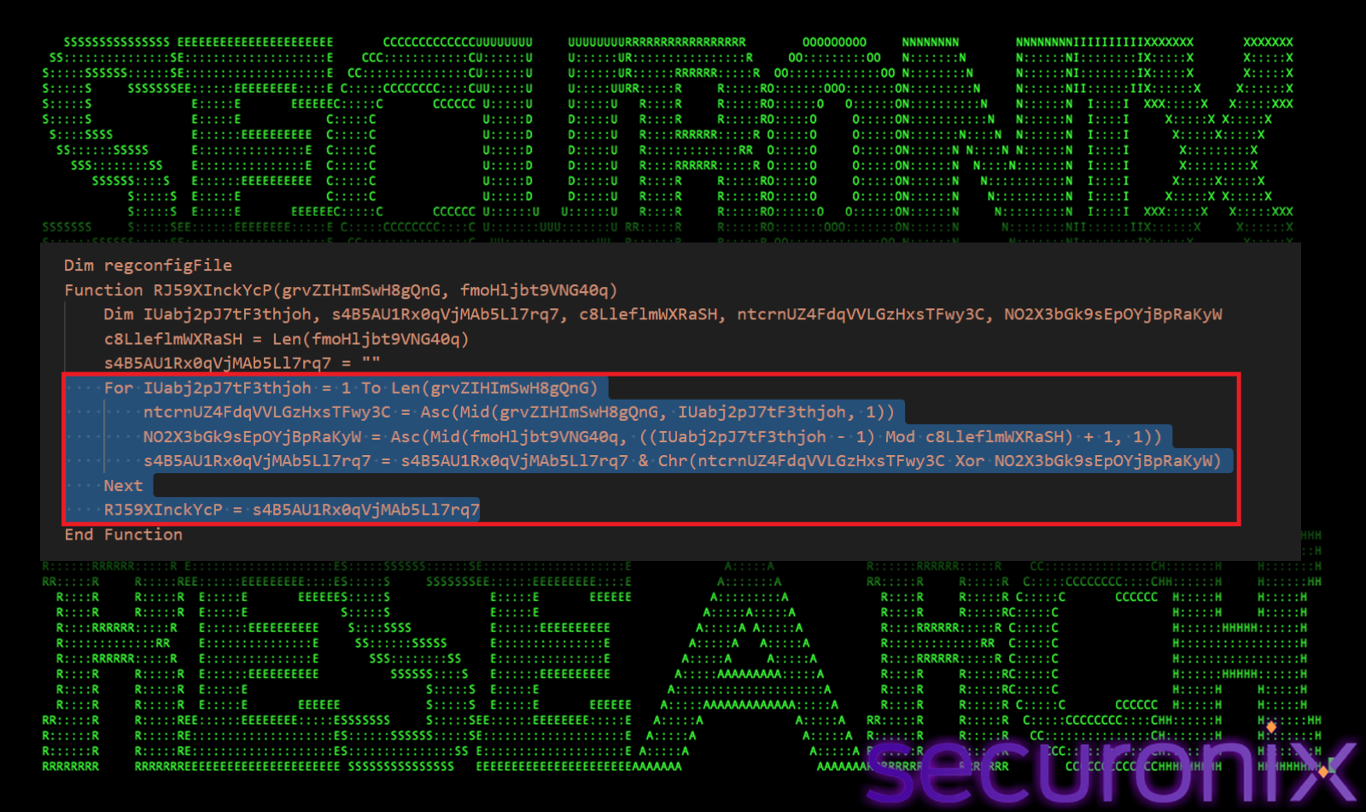

It results in a clean valid base 64 string. The script does not use the base64 decode function but instead uses com objects. It uses Msxml2.DOMDocument.3.0. Doing this we get a XOR key: 4qrttc9sl-sdnYziCVHb8g. Then the final layer of decryption comes. The encrypted data after cleaning and base64 decoding are decrypted by rolling XOR decryption, done by the function IUabj2pJ7tF3thjoh, (as shown in the image below).

Figure 6 XOR decryption loop

This loop iterates over every character of the encrypted data. It first gets a key length and then gets the numeric value of the current data character, then gets the specific key character and uses mod to roll the key if the data is longer than the key. It then performs XOR operation between the two values and then converts the result back to character.

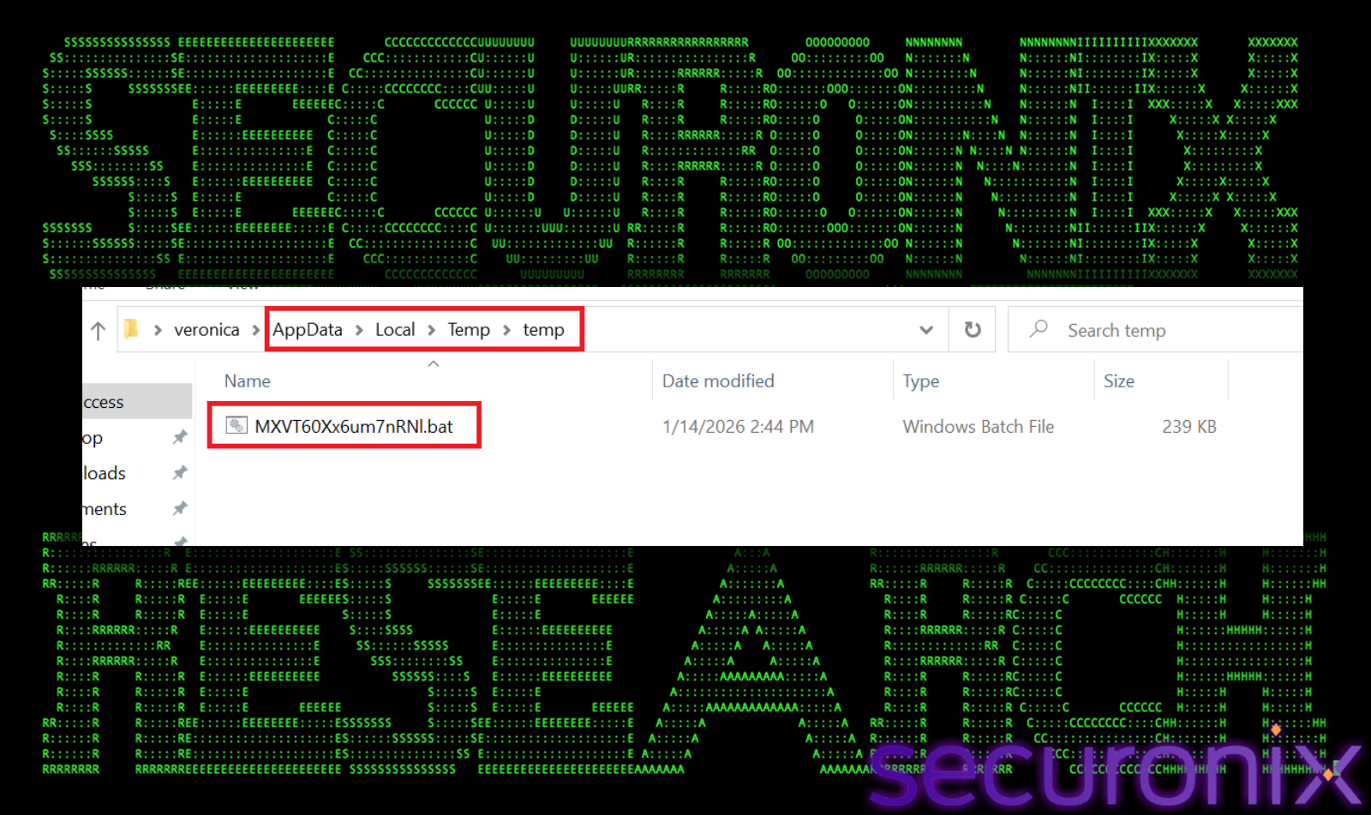

The decryption results in a valid Windows batch file. It creates a hidden directory %TEMP%\temp and and generates a random alphanumeric name then writes the decrypted batch file to this file.

File name : MXVT60Xx6um7nRNl.bat

Figure 7 3rd stage payload

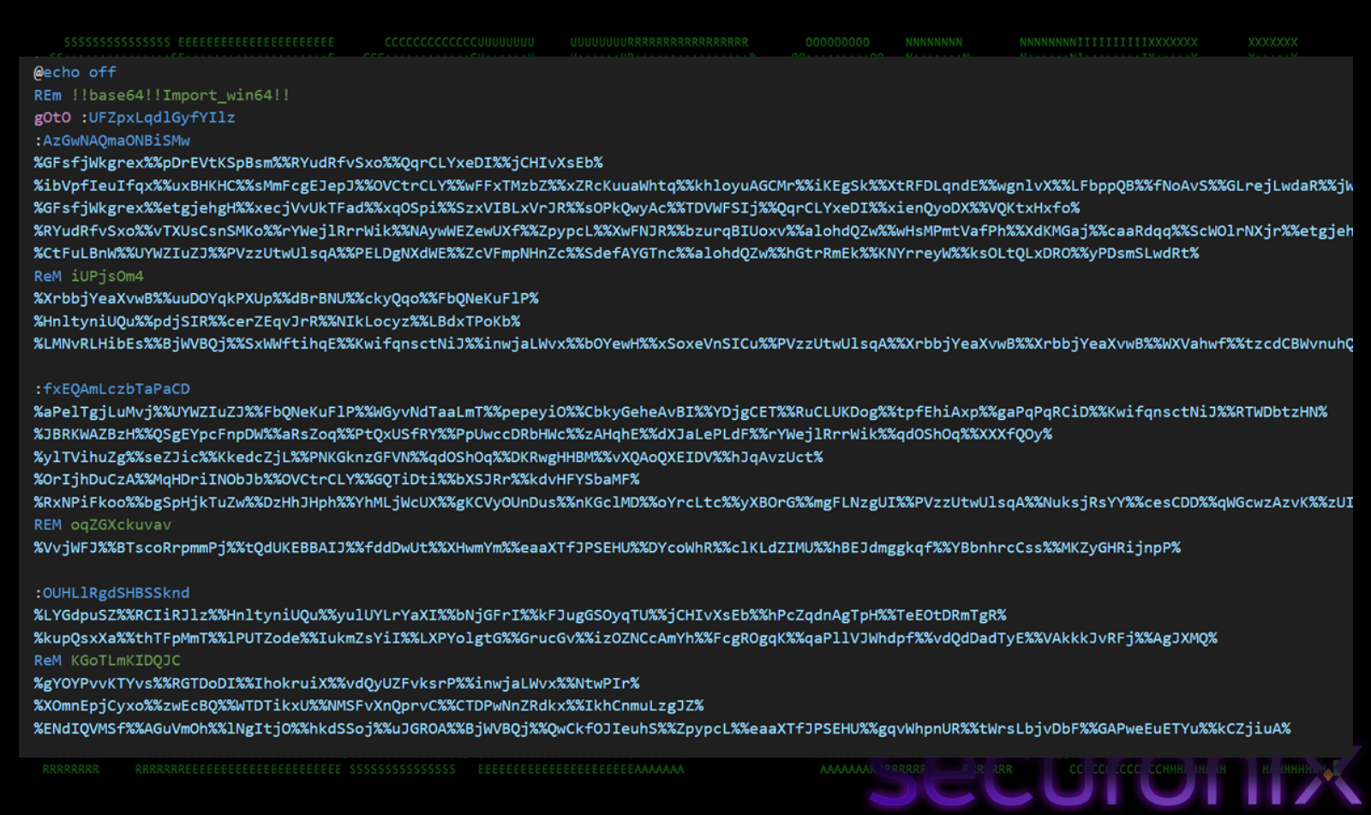

Stage 3: Batch code execution

The next payload in the attack chain is a heavily obfuscated batch file. The script also defines thousands of variables with random names (e.g., Set “YfYgeHItkMG=md”). We decoded the entire script, and it is performing two passes:

- Map: Collects all SET commands to build a dictionary of key=value pairs (e.g., %YfYgeHItkMG% -> md).

- Substitute: Replaced every instance of %VARIABLE% in the script with its gathered value.

Figure 8 Encoded Bat Script

Once deobfuscated, the actual logic became visible. Two critical PowerShell commands were uncovered that revealed the malware’s loading mechanism. The malware first sets up the environment (checks for Vmware, admin rights), drops/copies itself to rEgX.cmd, prowershell reads rEgX.cmd, finds the last line starting with @, decrypts the line (Base64-> XOR) and executes the decrypted payload in memory.

First, the script performs several environment checks to determine if it is running in a hostile environment or it is it has necessary privileges to proceed.

Anti-analysis techniques

Admin Privilege Check:

The script attempts to access a system-protected path or execute a command that requires elevation. It executes net session >nul 2>&1. If this command succeeds (%errorlevel% is 0), the script has Admin rights. If it fails (level 1 or 2), it does not. It checks for the username by executing, if /I %KyJXwvPFN%%username%%uAZebRKKq%%sGILJLZ%dmin if exist %KyJXwvPFN%%temp%\VBE exit. If the user is named ‘admin’ OR if a specific artifact file (‘VBE’, ‘mapping.csv’) exists, it terminates. This confirms it is defensive (hiding from analysts) rather than offensive (checking for root).

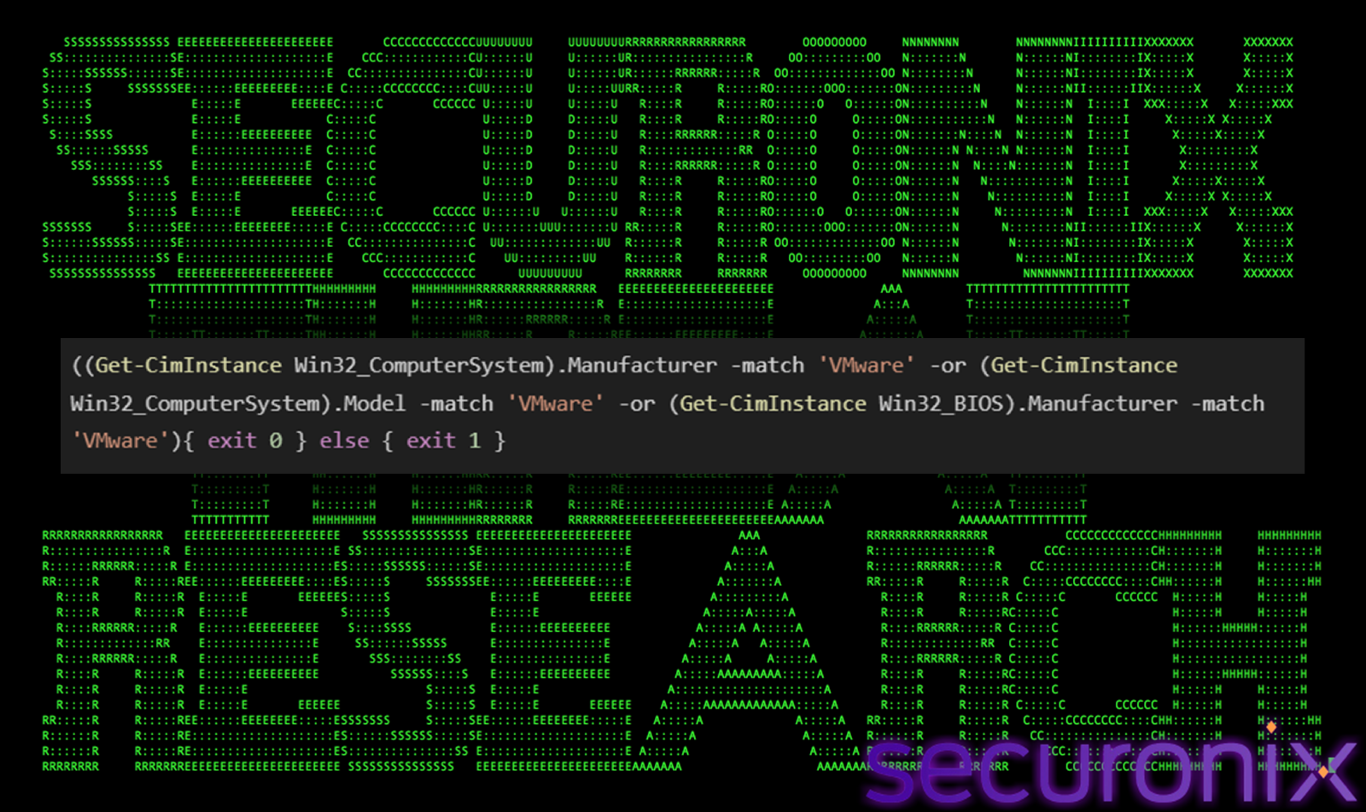

Vmware Detection

The script specifically looks for artifacts related to VMware. It executes below powershell command:

Figure 9 Anti-VM check

- Get-CimInstance Win32_ComputerSystem: Queries WMI for system information.

- -match ‘VMware’: Checks if the Manufacturer or Model fields contain the string “VMware”.

- Get-CimInstance Win32_BIOS: Queries BIOS information (often harder to spoof).

If matches found (exit 0): The script sets %errorlevel% to 0 (Success/True). The batch file likely interprets this as “Detected VM” and terminates. If no match (exit 1): Sets %errorlevel% to 1. The script proceeds.

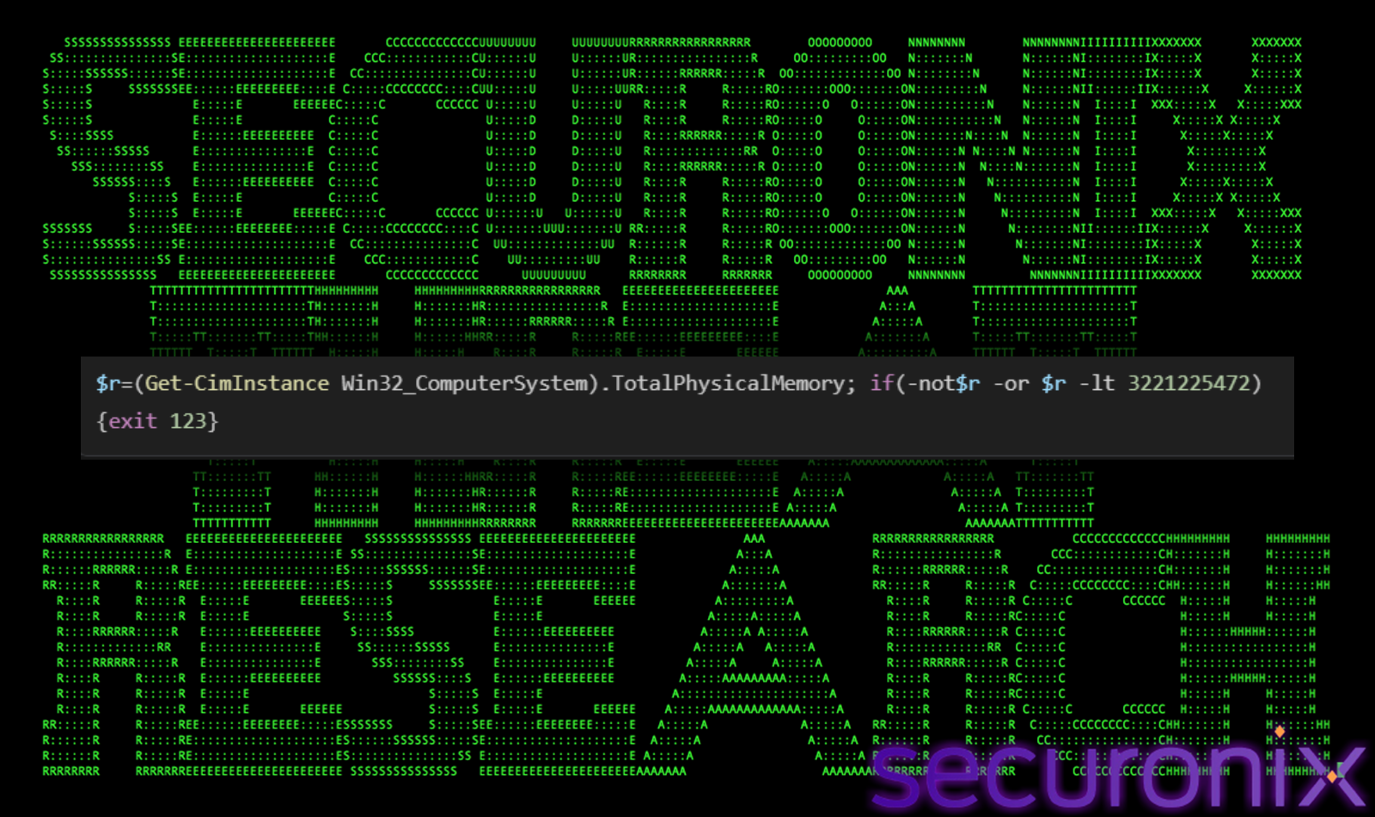

Memory Size Check (Anti-Sandbox)

Sandboxes are often configured with minimal resources (e.g., 2GB RAM). Malware checks for this to avoid running in low-resource environments, by running following command:

Figure 10 RAM check

- TotalPhysicalMemory: Gets the installed RAM in bytes.

- 3221225472: This value corresponds to 3 GB.

- Condition: If RAM is less than (-lt) 3 GB, it exits with specific error code 123.

- Batch Handler: if error level 123 exit /b. If the check fails (low RAM), the script terminates immediately.

Then the malware copies itself to “rEgX.cmd” and extracts the payload. We found a PowerShell command, which the malware uses to “read itself” and extract the hidden payload. This is a common but effective steganography-like technique used in script-based malware. The script first copies itself to a file named rEgX.cmd in %ProgramData% or Temp. It runs mbs.exe, which is a renamed copy of the legitimate powershell.exe, then it opens and reads the rEgX.cmd line-by-line using Get-Content. Since a batch file cannot easily “read” specific lines of itself into a variable without complex loop structures, it invokes PowerShell to do the heavy lifting of text parsing.

Figure 11 Self-Parsing Logic

It looks for a specific signature, which is that the line must start with @. There must be at least one space after the @ and then it captures everything else on the line. This specific pattern marks the hidden base64 payload we found at the end of the file. It takes the data and appends it to the out variable and makes a big block of text. Finally, it saves the extracted text to a new file named “windows.dll”. Despite the .dll extension it is a text file containing the base64 encoded payload that will be decrypted later.

Figure 12 Hidden payload at last line

We found another PowerShell command that looks like below:

Figure 13 In-Memory Trigger

This command is a payload decrypter and loader. It takes the fake windows.dll file created by the previous command, decrypts it, and executes the result in memory.

Firstly it sets up the key, In PowerShell/Bash/Batch, VARIABLE=’VALUE’ is a standard assignment structure. This strongly suggested that %YfYgeHItkMG% was acting as a placeholder for a variable name.The variable %YfYgeHItkMG% was set to “md”

sET “YfYgeHItkMG=md

To establish what %YfYgeHItkMG% represents, we searched for the file for where it was defined (SET). We found the following line (in the grep search):

sET “YfYgeHItkMG=$k”

By substituting the value back into the original PowerShell command, the logic becomes clear, this confirms that the PowerShell variable $k is being set to the string ‘md’.

Then it reads the entire content of the dll file as a single string and decodes the base 64 string into a byte array stored in $d.

$d=[Convert]::FromBase64String((Get-Content ‘windows.dll’ -Raw))

Lastly it decrypts the data by using the below code, this loop iterates through every byte ($b) of the decoded payload ($d) and we see how $k is used:

foreach($b in $d){$s+=[char](<$b -bxor [byte][char]$k[$idx]>); …}

- $b: The encrypted byte from the payload.

- -bxor: The Bitwise XOR operator.

- $k: The variable we identified earlier (‘md’).

This confirmed definitively that “md” is the rolling XOR key used to decrypt the payload. The malware author used Variable Indirection to hide the PowerShell syntax. Instead of writing $k=’md’, which is obvious to an analyst looking for keys, they wrote %RandomName%=’md’. This command contained the decryption routine:

$d=[Convert]::FromBase64String(…);

$s=”; $idx=0;

foreach($b in $d){

$s+=[char](<$b -bxor [byte][char]$k[$idx]>);

$idx++; …

}

iEx $s

Algorithm:

- Base64 Decode: The captured string from the @ line is decoded into bytes ($d).

- XOR Decrypt: Each byte is XORed (-bxor) with the key $k (‘md’). The key repeats (modulo index).

- Execute: The resulting string ($s) is executed immediately in memory using iEx (Invoke-Expression).

Lastly the malware uses iEx $S and executes it immediately in memory. The decrypted code never touches the disk.

The decrypted code comes out to be a PowerShell code. So the last line of the bat file starting with @ is actually an encrypted container and it holds the next stage of the malware, but it is locked or XOR encrypted and looks like text. The Windows.dll was a fake name. It was a dll which was just an text file holding the encrypted data.

Stage 4: In-Memory PowerShell execution

The payload extracted from the obfuscated batch file is a PowerShell-based process injector and persistence module, designed to operate as a long-lived loader rather than a simple dropper. Its primary role is to validate the execution environment, decrypt embedded payloads, establish persistence, and inject the final malware stage into legitimate Windows processes without writing decrypted artifacts to disk.

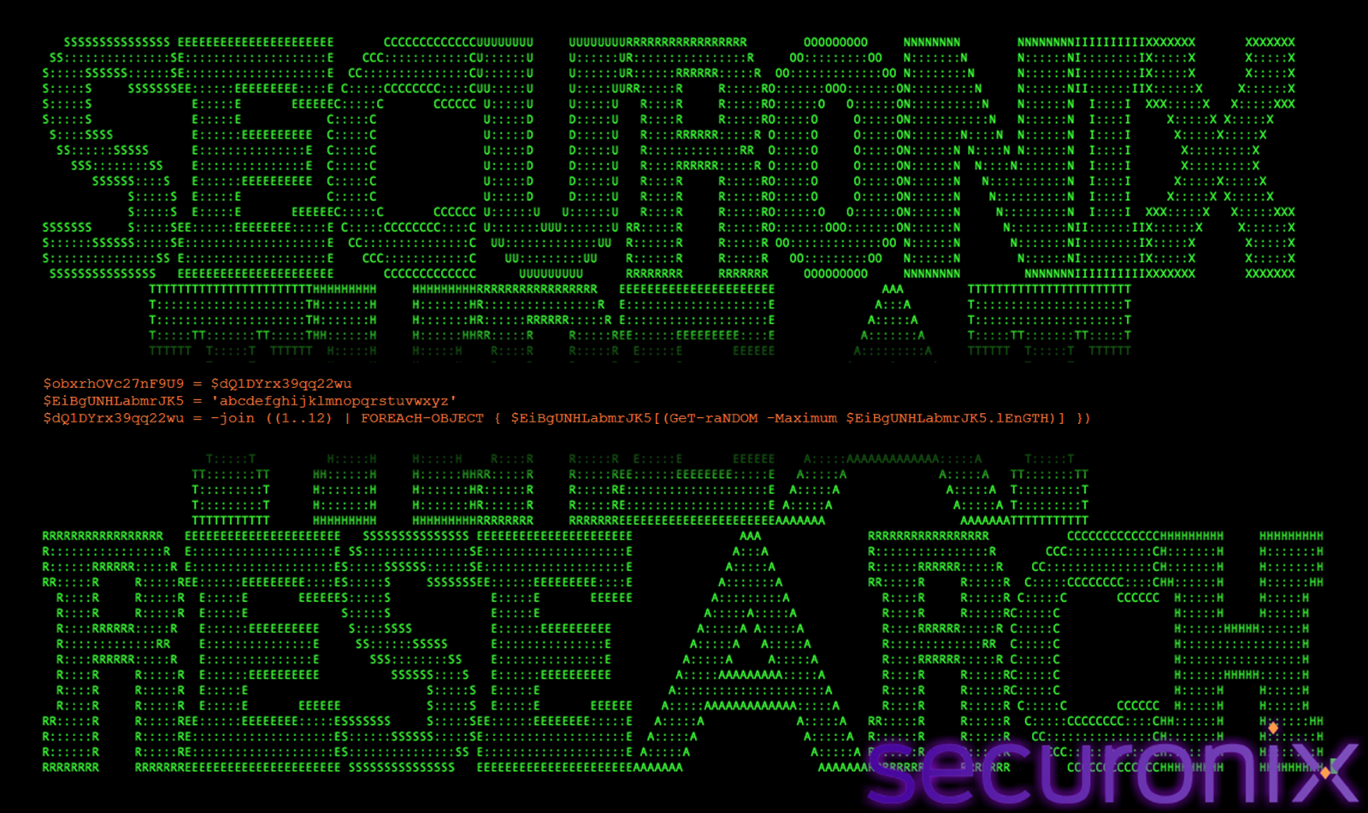

At the core of this stage is a custom multi-layer string obfuscation mechanism, implemented through the helper function fXZBcHpNzP. All sensitive strings are stored in obfuscated form and decrypted only at runtime using a combination of Unicode pollution, Base64 decoding, rolling XOR decryption, and a ROT-style character shift. This ensures that indicators such as file paths, API names, and WMI class identifiers never appear in cleartext within the script.

Execution flow is coordinated by the main orchestrator function hggeXeovZT, which performs environment validation (architecture and memory checks), sets up persistence via a hidden scheduled task and VBS launcher, retrieves and decrypts the next-stage payload, and manages process selection and injection. Supporting functions handle payload extraction (spSh7qdQND), target process enumeration (lBd8O3Vru8), reinfection prevention (iror9ZLn0o), and shellcode injection using native Windows APIs (A5mo0itEhn) exposed through a dynamically defined Win32 class.

Together, these components form a stealthy, resilient execution engine that delivers the final payload entirely in memory, blends into normal system activity, and survives reboots—reflecting modern fileless malware tradecraft.

fXZBcHpNzP() — Central String Deobfuscation Engine

The function fXZBcHpNzP() serves as the central string deobfuscation engine for the entire PowerShell loader. Every sensitive value used by the malware—including file paths, command strings, WMI class names, Win32 API identifiers, scheduled task definitions, and payload locations—is passed through this function before being consumed by the script. By consolidating all decoding logic into a single reusable routine, the malware ensures that no critical indicators are ever stored or referenced in cleartext, significantly reducing its static footprint and hindering straightforward analysis.

Figure 14 Deobfuscation Engine

To achieve this, fXZBcHpNzP() implements a four-layer deobfuscation pipeline executed at runtime. First, it removes intentionally inserted Greek Unicode characters using a regular expression, a tactic designed to break naïve string scanning and disrupt Base64 detection. Once cleaned, the string becomes valid Base64 and is decoded into raw bytes using [System.Convert]::FromBase64String(). These bytes are then decrypted via a rolling XOR operation, where each byte is XORed against a repeating integer key array, producing intermediate plaintext. Finally, a ROT-style Caesar shift is applied to alphabetic characters using arithmetic on ASCII ranges, further obscuring readable content. This layered approach ensures that meaningful strings are revealed only at the exact moment they are required, making static analysis and signature-based detection highly ineffective.

Add-Type Win32 — Native API Access Layer

The Add-Type Win32 section introduces a native API access layer by embedding a custom C# class directly into the PowerShell script. This technique allows the malware to invoke low-level Windows API functions that are normally inaccessible through standard PowerShell cmdlets. By doing so, the script elevates itself from a simple scripting-based loader into a fully capable execution framework with direct access to Windows internals.

Figure 15 Native API Access

Using Add-Type, the script dynamically compiles and loads a C# class named Win32, which exposes critical native APIs such as OpenProcess, VirtualAllocEx, WriteProcessMemory, CreateRemoteThread, ReadProcessMemory, and VirtualQueryEx. These APIs provide the fundamental primitives required for remote process injection. Importantly, this approach avoids dropping external binaries or invoking suspicious tools, allowing the malware to perform memory allocation, payload injection, and execution entirely from within PowerShell. By leveraging embedded C# instead of standalone executables, the script bypasses many traditional detection controls and implements full process injection capabilities in a fileless, stealth-oriented manner.

WYd5COb62n() — XOR Utility Decoder

The function WYd5COb62n() serves as a lightweight XOR decoding utility within the PowerShell loader. Unlike the more complex fXZBcHpNzP() routine, this function is designed for scenarios where minimal decoding is sufficient, such as handling short strings or simple encoded values. Its presence allows the malware to selectively apply simpler obfuscation techniques without invoking the full multi-layer decryption pipeline.

Figure 16 Lightweight Decoding

WYd5COb62n() operates by iterating over a byte array and applying a bitwise XOR operation against a supplied key value. Each decoded byte is then converted into its corresponding UTF-8 character and appended to the output string. This streamlined approach is computationally inexpensive and avoids unnecessary complexity when advanced obfuscation is not required. By mixing both heavy and lightweight decoding functions throughout the script, the malware reduces behavioral consistency and complicates pattern-based detection, while maintaining flexibility in how different strings and data elements are protected.

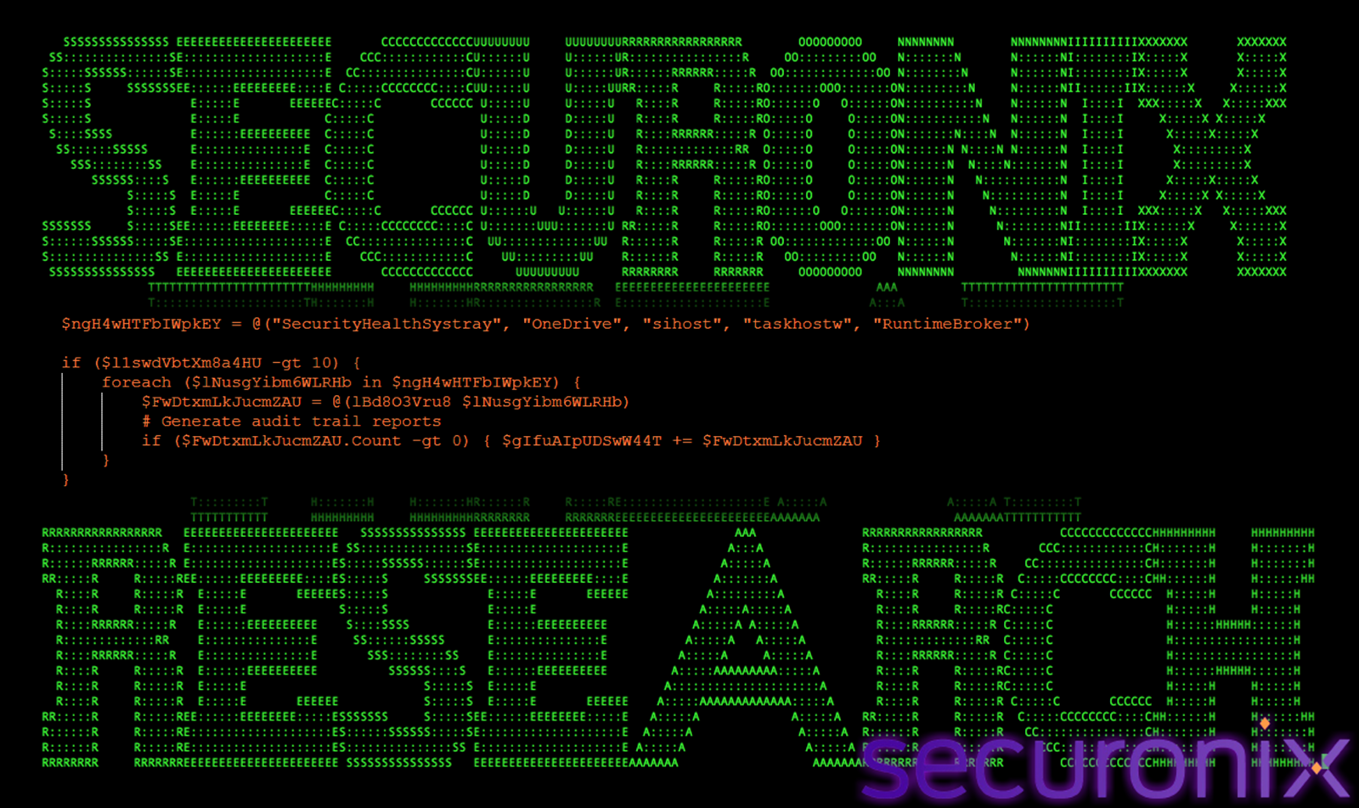

lBd8O3Vru8() — Target Process Enumeration

The function lBd8O3Vru8() is responsible for target process enumeration within the PowerShell loader. Its primary role is to identify running processes by name and return handles to those that match predefined criteria. This function acts as the selection mechanism for identifying suitable host processes into which the final payload will be injected.

Figure 17 Process Enumeration

Internally, lBd8O3Vru8() leverages PowerShell’s process enumeration capabilities to search for specific, trusted Windows binaries, including RuntimeBroker.exe, OneDrive.exe, taskhostw.exe, and sihost.exe. These processes are deliberately chosen because they are commonly present on modern Windows systems, digitally signed by Microsoft, and routinely generate background activity. By injecting into such processes, the malware effectively blends malicious execution into normal system behavior, reducing the likelihood of triggering behavioral detection or user suspicion. This targeted process selection is a key component of the loader’s stealth strategy, ensuring that payload execution occurs within legitimate execution contexts that are less likely to be scrutinized by security tools.

iror9ZLn0o() — Reinfection Marker Scanner

The function iror9ZLn0o() implements a reinfection prevention mechanism designed to ensure that the malware does not inject its payload multiple times into the same process. Rather than blindly injecting shellcode into every candidate process, this function acts as a safety check that verifies whether a target process has already been compromised.

Figure 18 Reinfection Marker Scanner

To perform this check, iror9ZLn0o() iterates through the target process’s committed memory regions using VirtualQueryEx and reads their contents via ReadProcessMemory. It scans each region for a predefined marker byte sequence:

DE AD BE CA FE BA EF

This marker is written into memory alongside the injected shellcode during the initial compromise. If the marker is detected, the function concludes that the process is already infected and skips reinjection. This logic prevents redundant shellcode execution, which could otherwise lead to process instability, crashes, or anomalous behavior that might alert defenders. The presence of a reinfection marker reflects mature attacker tradecraft, prioritizing operational stability and stealth over aggressive re-execution.

spSh7qdQND() — Payload Retrieval & Base64 Decoding

The function spSh7qdQND() is responsible for retrieving and decoding the next-stage payload from disk. Rather than loading a traditional executable or script, this function handles the extraction of an encrypted payload stored in a disguised on-disk container. It serves as the bridge between persistence logic and in-memory payload execution.

Figure 19 Payload Retrieval

spSh7qdQND() reads the entire contents of the payload file located at:

C:\ProgramData\IntelDriver\boot64x.w

This file does not contain a valid executable format. Instead, it stores the payload as Base64-encoded data polluted with a constant noise string. The function first removes this noise string using the central deobfuscation routine fXZBcHpNzP(), reconstructing a valid Base64 stream. Once cleaned, the function invokes [System.Convert]::FromBase64String() to decode the data into its raw binary form, returning shellcode bytes directly to memory. By treating the payload as a text container rather than an executable, this technique enables fileless payload staging, avoids static file-based detection, and ensures that the decrypted payload never exists on disk in a recognizable format.

A5mo0itEhn() — Shellcode Injection Routine

The function A5mo0itEhn() implements the remote shellcode injection routine used to execute the final malware payload inside a legitimate Windows process. This function is responsible for transitioning the attack from script-based execution into native, memory-resident code execution, allowing the payload to run without creating a standalone process or dropping a decrypted executable to disk.

Figure 20 Shellcode Injection Routine

A5mo0itEhn() follows the classic open → allocate → write → execute injection pattern. It begins by opening a handle to the selected target process using OpenProcess, requesting only the minimal privileges required for memory operations and thread creation. This reduced access footprint helps avoid access-denied errors and lowers behavioral suspicion. Once a valid handle is obtained, the function allocates executable memory within the target process using VirtualAllocEx with read, write, and execute permissions. It then writes a predefined marker byte sequence into the allocated region, followed immediately by the decrypted shellcode using WriteProcessMemory. Execution is triggered via CreateRemoteThread, with the thread’s entry point set to the beginning of the injected shellcode. After execution is initiated, the function waits for the remote thread to run and cleans up handles to maintain stability. By executing entirely within the context of a trusted, signed Windows process, this technique enables the malware to blend into normal system activity and significantly complicates detection and forensic analysis.

hggeXeovZT() — Execution Orchestrator & Persistence Controller

The function hggeXeovZT() serves as the primary execution orchestrator and persistence controller for the PowerShell loader. Rather than performing a single discrete task, this function coordinates the entire lifecycle of Stage 4 execution, including environment validation, persistence establishment, payload retrieval, target process selection, reinfection prevention, and shellcode injection. It acts as the central control loop that determines when and how the remaining functions are invoked, transforming the script from a simple loader into a resilient, long-lived malware framework capable of maintaining covert execution across reboots while adapting to the execution environment.

Figure 21 Execution Orchestrator & Persistence Controller

Responsibilities:

Environment Validation: Memory / Sandbox Detection

This stage determines whether the malware is executing in a real user environment or an automated analysis sandbox.

Figure 22 Sandbox Detection

This check is intentionally placed at the very beginning to prevent deeper execution in automated sandboxes, which commonly operate with minimal memory. The logic is wrapped in a try/catch block with a fallback CIM query, ensuring the check remains effective even if one method fails.

Persistence Identifier Initialization

This step initializes a unique identifier used across all persistence-related artifacts.

$ve4ZYlZvaBrzkoI = “ocZpcnZkaclvkdhsyaocvoaxkzpaiywq”

This hardcoded string acts as a base identifier for all persistence artifacts created by the malware. It is reused as:

- Scheduled task name

- VBS filename

- XML task definition name

Using a single identifier allows the malware to track whether persistence already exists and avoids recreating artifacts unnecessarily.

Persistence Check: Scheduled Task Presence

Before creating persistence, the malware checks whether persistence already exists on the system.

Figure 23 Persistence Check

Before creating persistence, the function checks whether the scheduled task definition already exists. If the XML file is present, the persistence setup phase is skipped.

This prevents duplicate task creation and reduces noise that could alert defenders or cause operational instability.

Persistence Setup: Scheduled Task + VBS Launcher

This phase establishes stealthy, reboot-resilient persistence.

Figure 24 Persistence Setup

If persistence is not present, the function creates a hidden scheduled task that triggers at user logon. Instead of launching PowerShell directly, the task executes wscript.exe, which runs a Visual Basic Script (VBS).

This indirection serves two purposes:

- Avoids obvious PowerShell indicators in scheduled task metadata

- Allows flexible payload replacement without modifying the task

The VBS script acts only as a launcher, executing the next-stage batch or PowerShell logic.

Persistence Rotation Logic (Self-Healing)

This logic enables the malware to recover persistence if artifacts are removed or flagged.

Figure 25 Persistence Rotation

If an existing persistence artifact is detected, the malware:

- Deletes the old scheduled task

- Generates a new randomized task name

- Recreates the scheduled task and VBS launcher

This behavior allows the malware to self-heal and evade signature-based detection that relies on fixed task names or filenames.

Payload Retrieval Initialization

Once persistence is confirmed, the loader prepares to load the next execution stage.

Figure 26 Payload Retrieval Initialization

After persistence is confirmed, the function retrieves the next-stage payload from disk. The path to the payload file (boot64x.w) is decoded at runtime using fXZBcHpNzP() and passed to spSh7qdQND(), which removes noise strings and Base64-decodes the content.

The result is raw shellcode bytes, held entirely in memory.

Target Process Enumeration

This stage selects suitable host processes for payload execution.

Figure 27 Target Process Enumeration

The function defines a list of trusted Windows processes that are commonly present on modern systems. These processes:

- Are signed by Microsoft

- Perform background operations

- Generate regular system activity

Injecting into these processes allows the malware to blend into legitimate behavior.

Reinfection Detection

This check ensures that the same process is not infected multiple times.

Figure 28 Reinfection Detection

Before injecting shellcode, the function scans each candidate process using iror9ZLn0o(). This helper function searches memory for a predefined marker byte sequence:

DE AD BE CA FE BA EF

If the marker is found, the process is assumed to be already infected and is skipped.

This prevents:

- Duplicate injections

- Process crashes

- Behavioral anomalies

Shellcode Injection Execution

This phase executes the final payload inside a selected target process.

if (A5mo0itEhn $EdIyRahUpXF4VkV $tiGr1TBour3O1Av) {

# Initialize thread management

$XhMRlTbvtd56NpG = $true

break

}

When a suitable process without an infection marker is found, the function calls A5mo0itEhn() to perform remote process injection. This routine allocates RWX memory, writes the shellcode, and executes it using CreateRemoteThread.

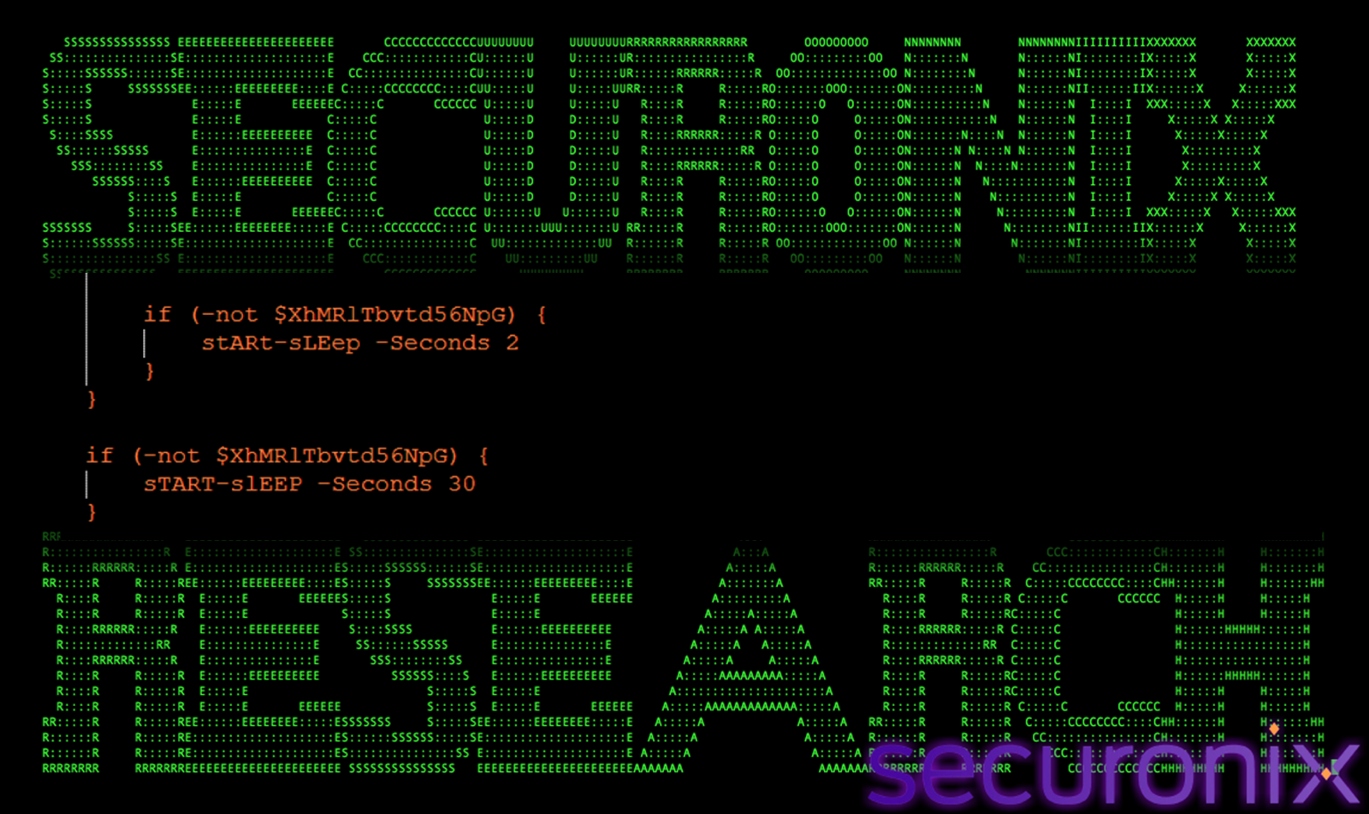

Upon successful injection, the function exits the loop and enters a sleep cycle to reduce execution noise.

Execution Throttling and Stability Control

This final step controls execution timing to maintain stealth.

Figure 29 Execution Control

The function intentionally throttles execution using sleep intervals. This:

- Reduces CPU usage

- Avoids suspicious rapid API activity

- Makes runtime behavior less anomalous

Shellcode Payload Analysis

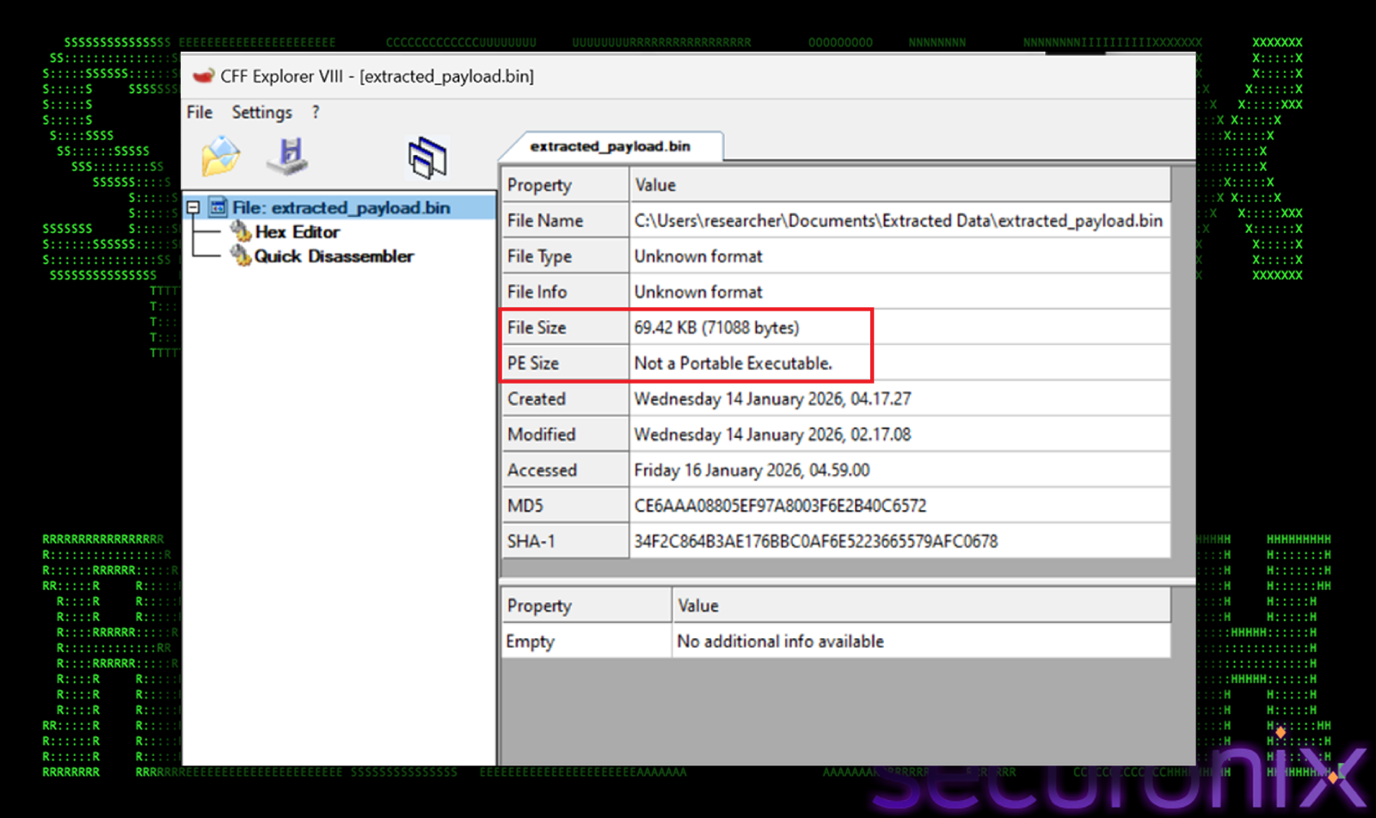

The final payload produced by the PowerShell loader is raw x64 shellcode, approximately 71 KB in size. Initial static inspection revealed that the payload does not contain a valid Portable Executable (PE) header (i.e., no MZ signature), confirming that it is not a conventional executable or DLL.

Figure 30 Final Payload

Additionally, the shellcode contains no human-readable strings and exhibits very high entropy (>7.7), strongly indicating that the payload is either encrypted or tightly packed. These characteristics are consistent with modern in-memory malware stagers, which are specifically designed to evade static file-based detection and signature scanning.

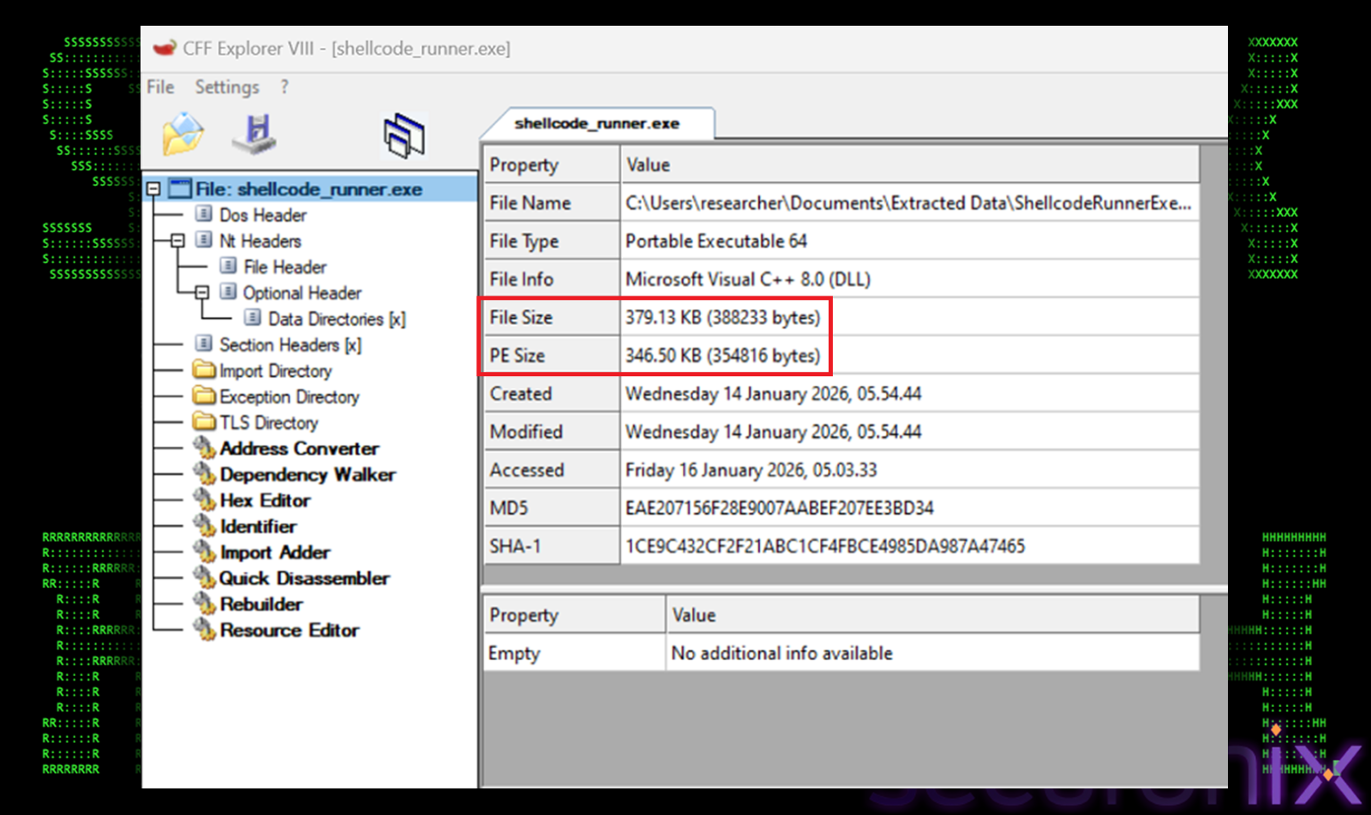

To further analyze and validate the functionality of the shellcode, the payload was extracted from the obfuscated container file (boot64x.w) after completing the Base64 and XOR decryption stages. At this point, the payload existed solely as a raw byte sequence with no inherent execution context. To enable controlled analysis, a minimal C wrapper (runner stub) was created.

Figure 31 Raw Byte sequence of final payload

This stub allocated executable memory at runtime, copied the shellcode into the allocated region, and transferred execution flow to it.

The C wrapper was compiled using the gcc compiler, producing a standalone executable that served only as a controlled launcher for the shellcode. This approach is commonly used in reverse engineering workflows to safely observe the runtime behavior of shellcode that would otherwise execute exclusively via process injection. Importantly, this executable was deployed and executed only within an isolated reversing laboratory environment to prevent unintended propagation or system compromise.

Figure 32 Compiled Payload

Once compiled, the executable was subjected to static and dynamic inspection. Static scanning immediately revealed multiple indicators consistent with known AsyncRAT implementations. Dynamic execution further confirmed this attribution: the shellcode initialized network communication routines, established encrypted command-and-control behavior, and exposed functionality associated with remote surveillance and control. These behaviors matched well-documented AsyncRAT operational patterns, including memory-resident execution and modular command handling.

This validation step was critical in confirming that the PowerShell loader and injection framework existed solely to deliver AsyncRAT spyware into memory. Rather than embedding AsyncRAT directly as a script or executable, the attackers intentionally encapsulated it as encrypted shellcode, ensuring that the final payload never appears on disk in a recognizable format. This design significantly complicates detection, as the malicious logic only becomes visible after multiple layers of decryption and in-memory execution.

In summary, the shellcode analysis conclusively demonstrates that the final stage of this multi-layer infection chain is a fully functional AsyncRAT implant, delivered through a fileless execution model. The use of encrypted shellcode, runtime injection, and trusted host processes reflects mature attacker tradecraft aimed at maintaining stealth, persistence, and operational stability while evading modern endpoint security controls.

AsyncRAT Capabilities & Impact

Static and behavioral analysis of the decrypted shellcode conclusively identified the final payload as AsyncRAT, a widely abused open-source Remote Access Trojan (RAT) that provides attackers with comprehensive control over compromised systems. AsyncRAT is frequently adopted by both low-skill threat actors and organized groups due to its modular design, ease of customization, and extensive post-exploitation feature set.

At its core, AsyncRAT establishes a persistent command-and-control (C2) channel with an attacker-controlled server, typically over encrypted TCP or TLS connections. Once communication is established, the RAT operates asynchronously, allowing attackers to issue commands and receive results in real time without interrupting the victim system’s normal operation. This asynchronous execution model enables long-running background activity while minimizing noticeable performance degradation.

AsyncRAT includes a broad range of surveillance and data collection capabilities. Keylogging functionality captures keystrokes at the operating system level, allowing attackers to harvest credentials, chat messages, and sensitive user input. Screen capture and webcam access provide real-time visual monitoring of user activity, enabling credential theft, reconnaissance of internal applications, and direct observation of sensitive workflows. Clipboard monitoring further supplements these capabilities by capturing copied data, such as passwords or confidential text.

In addition to surveillance, AsyncRAT provides extensive file system access. Attackers can enumerate directories, upload and download files, and exfiltrate sensitive documents on demand. This enables both opportunistic data theft and targeted exfiltration of high-value information. The RAT also supports remote command execution, allowing arbitrary system commands or additional payloads to be executed on the compromised host. This capability is often used to deploy secondary tools, escalate privileges, or pivot laterally within a network.

Persistence is another defining characteristic of AsyncRAT deployments. Once installed, the RAT can maintain execution across system reboots using a variety of mechanisms, including registry autoruns, scheduled tasks, or script-based launchers, often tailored to the delivery method used. In this campaign, persistence is reinforced by a stealthy PowerShell loader and scheduled task infrastructure, ensuring that AsyncRAT is relaunched reliably without user interaction.

The impact of an AsyncRAT compromise extends well beyond initial access. Persistent, covert control allows attackers to conduct long-term espionage, silently monitor user behavior, and exfiltrate data over extended periods. Compromised systems can also be leveraged as footholds for follow-on attacks, including lateral movement, deployment of ransomware, credential harvesting across the environment, or use as staging points for additional malware campaigns.

In this specific infection chain, the decision to deliver AsyncRAT as encrypted, memory-resident shellcode significantly increases its stealth. The payload never appears on disk in a recognizable executable form and runs within the context of trusted Windows processes. This fileless execution model makes detection and forensic reconstruction substantially more difficult, allowing AsyncRAT to operate with a reduced risk of discovery by traditional endpoint security controls.

Overall, the presence of AsyncRAT as the final payload confirms that this campaign is not opportunistic malware, but a deliberate, full-featured remote access operation. The sophistication of the delivery chain, combined with AsyncRAT’s capabilities, underscores the threat posed by script-based, multi-stage attacks and highlights the need for memory-level monitoring, behavioral detection, and cross-stage correlation in modern defensive strategies.

Conclusion:

This campaign illustrates how modern adversaries increasingly win not through novel malware, but through disciplined tradecraft and clever abuse of legitimate system features. By chaining trusted file formats, layered scripting, and in-memory execution, the attackers effectively sidestep many traditional controls while maintaining stealth and resilience. For defenders, the takeaway is unambiguous: visibility must extend beyond individual indicators to encompass execution context, behavioral correlation, and memory-level activity. As fileless, multi-stage attacks continue to mature, detection strategies must evolve accordingly, or risk being perpetually one step behind.

Securonix recommendations

- Vigilance Against Disk Image Formats: This campaign strategically utilizes Virtual Hard Disk (VHD) files hosted on IPFS infrastructure to bypass email gateway filters.

- Maintain an extra sense of vigilance regarding unsolicited emails containing disk image attachments such as .VHD, .ISO, or .IMG.

- Avoid clicking on external links to download these file types, as they are frequently used as primary delivery vehicles for multi-stage payloads.

- Educate users that mounting these containers from unknown sources allows attackers to bypass the Windows Mark-of-the-Web (MotW) security feature, enabling malicious files inside to execute without standard untrusted file warnings.

- Enhance System Visibility: In Windows environments, ensure that file extension visibility is enabled for all users to help identify disguised files (e.g., invoice.pdf.vhd).

- Monitor Script Staging and Execution: The Dead#Vax delivery framework relies on a cascading chain of WSF, Batch, and PowerShell scripts.

- Monitor common malware staging directories, specifically looking for script-related activity in world-writable folders such as %TEMP%, %APPDATA%, or user home directories.

- Batch scripts used in these campaigns can often be inspected by opening them in a secure text editor prior to execution to identify heavily obfuscated commands or self-parsing logic.

- Advanced In-Memory Detection: Since the final payload is injected directly into trusted processes (such as Explorer.exe or OneDrive.exe) and never exists on disk in a decrypted state, signature-based tools may fail.

- Deploy robust endpoint logging, such as Sysmon, to monitor for Win32 API calls associated with process injection, including VirtualAllocEx, WriteProcessMemory, and CreateRemoteThread.

- Proactive Memory Hunting: Security teams should use memory forensics or custom scanners to hunt for the specific reinfection marker: DE AD BE CA FE BA EF.

- The presence of this byte sequence within the memory space of legitimate Windows processes serves as a high-confidence indicator of an active Dead#Vax infection.

- PowerShell Logging and Response: We strongly recommend enabling PowerShell Script Block Logging (Event ID 4104) to aid in detection.

- This provides visibility into the deobfuscated code at runtime, which is critical when the malware uses multi-layer encryption like rolling XOR and ROT-style shifts.

- Incident Remediation: Securonix customers can scan their environments using the hunting queries provided below to identify VHD mounting events, unusual scheduled tasks, and unauthorized process injections.

MITRE ATT&CK Matrix

| Tactics | Techniques |

| Initial Access | T1566.001 – Phishing: Attachment

T1566.002 – Phishing: Link |

| Execution | T1059.001 – Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell

T1059.003 – Command and Scripting Interpreter: Windows Command Shell T1059.005 – Command and Scripting Interpreter: Visual Basic T1059.007 – Command and Scripting Interpreter: JavaScript / WSF |

| Persistence | T1053.005 – Scheduled Task/Job: Scheduled Task |

| Defense Evasion | T1027 – Obfuscated Files or Information

T1027.002 – Obfuscated Files or Information: Software Packing T1140 – Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information T1218 – Signed Binary Proxy Execution T1497.001 – Virtualization/Sandbox Evasion: System Checks |

| Credential Access | T1056.001 – Input Capture: Keylogging |

| Discovery | T1082 – System Information Discovery |

| Command and Control | T1071.001 – Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols

T1573 – Encrypted Channel |

| Exfiltration | T1041 – Exfiltration Over C2 Channel |

| Impact | T1565.001 – Data Manipulation |

Relevant Securonix detections

- EDR-ALL-80-RU

- EDR-ALL-206-RU

- EDR-ALL-1215-ERR

- EDR-ALL-1226-RU

- EDR-ALL-1280-RU

- PSH-ALL-316-RU

- WEL-ALL-1186-ERR

Relevant hunting queries

(remove square brackets “[ ]” for IP addresses or URLs)

- index = activity AND rg_functionality = “Next Generation Firewall” AND (destinationhostname CONTAINS “mingyitc.com” OR destinationhostname CONTAINS “w3s.link”)

- index = activity AND rg_functionality = “Endpoint Management Systems” AND (deviceaction = “Process Create” OR deviceaction = “Process”) AND (destinationprocessname ENDS WITH “mbs.exe” OR childprocesscommandline CONTAINS “mbs.exe”)

- index = activity AND rg_functionality = “Endpoint Management Systems” AND (deviceaction = “File created” OR deviceaction = “File created (rule: FileCreate)”) AND (TargetFileName CONTAINS “windows.dll” OR TargetFileName CONTAINS “boot64x.w” OR TargetFileName CONTAINS “rEgX.cmd”)

- index = activity AND rg_functionality = “Endpoint Management Systems” AND (deviceaction = “File created”) AND customstring49 CONTAINS “\temp\temp\” AND customstring49 ENDS WITH “.bat”

- index = activity AND rg_functionality = “Endpoint Management Systems” AND (deviceaction = “Network connection detected”) AND (destinationprocessname ENDS WITH “RuntimeBroker.exe” OR destinationprocessname ENDS WITH “OneDrive.exe” OR destinationprocessname ENDS WITH “sihost.exe” OR destinationprocessname ENDS WITH “taskhostw.exe”)

C2 and infrastructure

| C2 Address |

| mingyitc[.]com

https://bafybeiaj6jw2xhbppgji757tn3hg5uu6splaa5gyydkwnzwprzakcp44ve.ipfs.w3s[.]link/PurchaseOrder_0006094050126_%20Procomps_Docx[.]vhd 217.64.148.120 aassecc.ydns.eu asseccmod.ydns.eu |

Analyzed files/hashes

| File Name | SHA256 |

| EXTERNALProcomps Purchase Order #0006094.msg | 365265cf9749d7b04d2c037449cbfae23bcb75ed6e2eb1f161ca680e94ca466e |

| Procomps Purchase Order #0006094.msg | a048fc039ba6d1e22736c9142998de79445f878136664958f9b11156aaf1b61f |

| PurchaseOrder_0006094050126_%20Procomps_Docx.vhd | 7fa075ed827095b4531cb35f650ccf6345c3799734e4ed30d9f52e72c0711713 |

| PurchaseOrder_0006094050126_ Procomps_pdf.wsf | 7e4646d0cf91153653c5e366f98a65aad5ef363e0edeb246c809f53085971453 |

| tPr3tnrl3A9seMEY.bat | 3d3342af3608399704d5daf9dc061ad1f8b243531fd9ef8497a10c6a9dd59661 |

| boot64x.w | b77312ea8cdec4a33be790cf9587a93389b56e735a3c9560cd9116a4b115e2ec |

| Injected powershell code | bcccb21d96d0ed7d6d1bb2e33e9981287addb94314b3cbbd9d5d7332c47f7b80 |

| AsyncRAT | 601d9deea6467a57e42c355d481331cd78d6487bd160a081332420c69f214455 |

| AsyncRAT | daac2fe0fe9a71f531d9b35c9ca269c0bdfbd1bbac5e8d73fc91afcff20ef524 |

| AsyncRAT | 7bb7c893fdf7f7ccd998610969d23993c50fc0b693e67930b6f98d8dbd003ee3 |

| AsyncRAT | ececf197bee885791a9b13cd48c131eec76d8431f1907f9d55b6c9330b57a85e |

| AsyncRAT | 346e8e54578f206200f7815d0e315e6bfb58198b5ff96d8bcec02863e5b42cc7 |

| AsyncRAT | 0c0b5dfb2e01c5ddd043ac32e2f7176b4ba439d4e3ea37ca04e4b17aa283d4e7 |

| AsyncRAT | 4c6c9ec88d00a3b77e6288afc4ee9974ac07a2c73012c3e1a017c457dcf22d87 |